It’s easy to forget now, but Jay-Z took the long road to superstardom.

It was in 1998 that Jay finally hit the mark with a combination of street savvy and radio-friendly singles. His early career had been marred by false starts, his brilliant 1996 debut had gone unnoticed by mainstream audiences and his follow-up was trashed by critics. But 1998 was when he finally got the world’s attention. By 2001, he was arguably the most influential rapper in hip-hop. Even losing his highly-publicized feud with Nas didn’t diminish his commercial appeal or cultural sway.

Younger fans probably can’t envision a hip-hop universe where Jay-Z isn’t the icon he is today. And many older fans — still overly enamored with the departed 2Pac and Notorious B.I.G. — have taken for granted the significance of the Brooklyn, N.Y.-born rhymer. Fifteen years after he finally broke through, it’s interesting to take note of what Jay-Z’s ascendance meant for hip-hop — and why it happened the way that it did.

Generation Xers love to romanticize 1990s hip-hop — and for good reason, it was a brilliant era of music. One facet of that era that goes under-acknowledged, however, is the genre’s penchant for romanticized fatalism. In terms of subject matter and aesthetics, it was a bleak time in mainstream hip-hop. 2Pac and Biggie routinely rapped about their own deaths—song titles like “If I Die 2Nite,” “Ready To Die,” and “You’re Nobody Til Somebody Kills You” made the idea of being dead by 25 seem almost noble. Bone Thugs N Harmony sang elegies like “Crossroads” and Mobb Deep videos depicted a bleak, almost nihilistic reality in regards to young, black males and their indifference towards their futures.

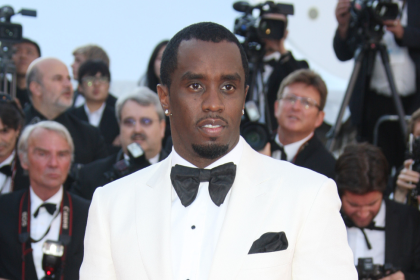

After the tragic murders of 2Pac and Biggie, hip-hop was offered the shiny-suit escapism of Puffy, Ma$e and Missy Elliott — but it was the emergence of Jay-Z that truly set the table for how hip-hop artists and audiences would approach the genre heading into the new millennium. Jay-Z made his ambitions clear — he wasn’t interested in dying at 25, he was interested in winning. And that optimism resonated with a generation of upwardly-mobile young black people heading into the college classrooms and corporate America at the turn of the century. He spoke a language that resonated equally with the weight-pushin’ corner hustler and the white collar cubicle-jockey; and that dual voice went on to become his stock-in-trade. In 1997, Biggie posed on his album cover next to a Hearse. In 1998, Jay posed next to a Bentley.