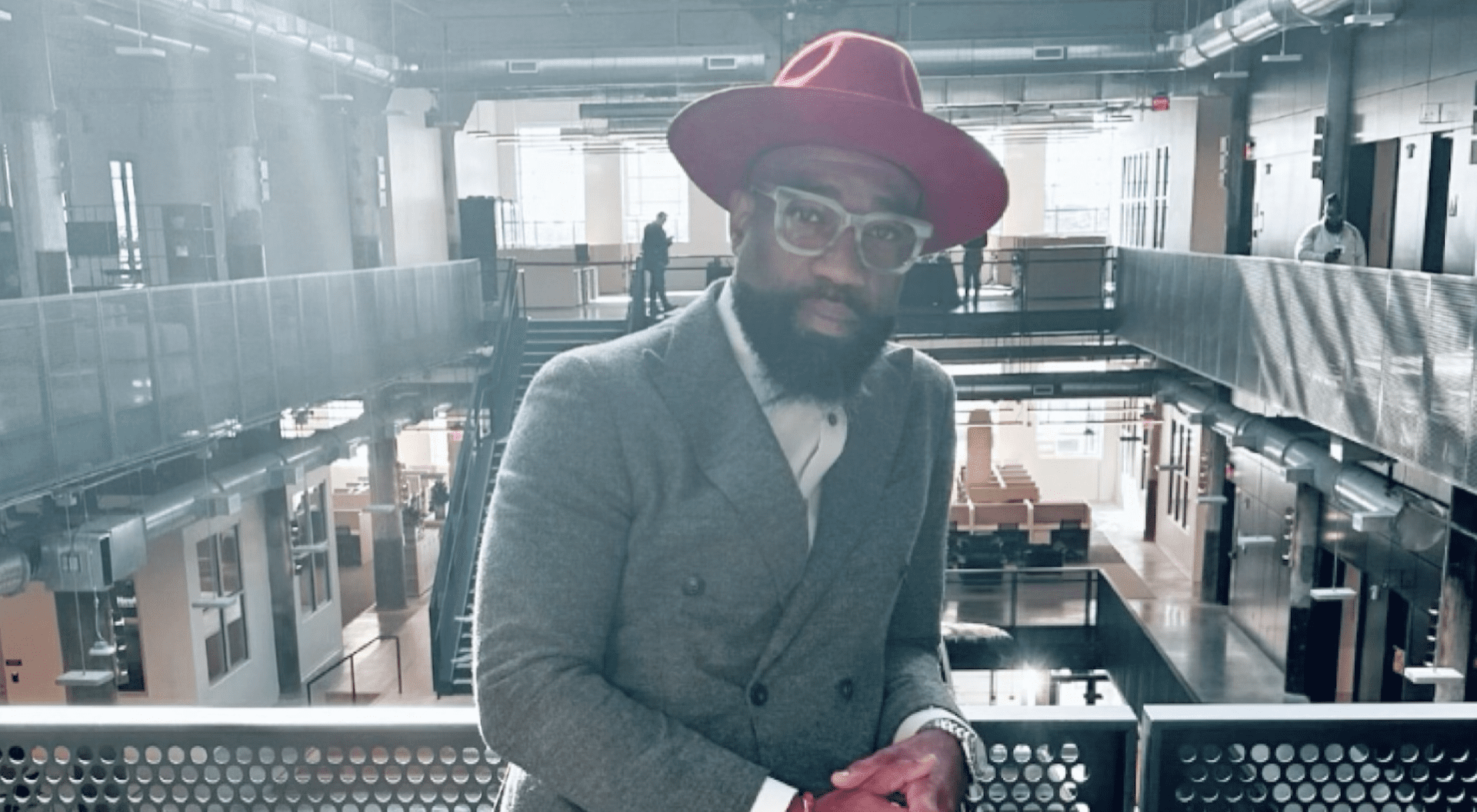

As the CEO of URGE Development Group, Detroit’s Roderick Hardamon prides himself on building communities through innovation and value creation. He’s a visionary real estate developer whose journey from Wall Street to his hometown neighborhoods in Detroit, reflects a profound commitment to transformation. Dissatisfied with the limitations of his corporate career, Hardamon ventured into real estate, driven by a desire to empower communities and shape destinies. With a background in mergers and acquisitions, he learned that resilience and self-belief are crucial, as evidenced by a pivotal negotiation in Amsterdam during his Wall Street days.

Inspired by childhood experiences with Monopoly and Legos, Hardamon infuses creativity into his projects at URGE, where cultural investment and financial commitment converge. His projects in Detroit exemplify a creative pacemaker ethos, blending historical homage with modern beauty and a strong arts emphasis.

Now a seasoned entrepreneur, Hardamon shares invaluable advice for aspiring developers: passion over profit, commitment over convenience. He emphasizes expertise, hard work, and community engagement as the keys to success in an industry that demands dedication and resilience. With an estimated impact of over $100 million invested in Detroit in under four years, Hardamon’s story is a testament to the transformative power of unwavering commitment and positive community impact.

Rolling out spoke more with him about how he’s looking to pay it forward by educating the new generation on investing and developing.

Tell us about your journey.

I had my ultimate job, and it wasn’t enough. When I realized that it wasn’t enough, and getting a bigger job wasn’t enough, either, I decided it was time for me to leave and figure out my life. I realized that real estate was going to be my path forward. To be able to come back home and invest in communities helped not only decide my destiny but the destiny of others and empower folks to be able to make decisions that control their own lives. That’s why I started a development firm so that we could put money into capital work and communities that we chose, build the buildings that we chose, hire the folks that we chose, and have the impact that we thought was necessary.

How would you describe your transition from Wall Street to betting on yourself?

That transition from Wall Street to running my own company was super hard. [When] I decided that [it] was time for me to leave, it wasn’t until three years later that I left. It took a lot of financial planning, but the biggest hurdle was me believing that I could be self-sufficient on my own. It was me believing that it wasn’t just Citigroup, my former firm’s business card, or their logo that got me in the room, but that I was as equally valuable to the process and to the impact I was having. When you’re in a big corporation, sometimes it feels like it’s the firm. It feels like “without that branding, what can you do?” Will people pick up the calls and listen anymore? Some of my closest friends reminded me it wasn’t the logo doing all the work. It wasn’t the logo that got promoted. “They wouldn’t have invested all that money and paid you all that money if you weren’t having real impact everyday.” They wouldn’t have allowed me the flexibility to commute between Detroit and New York unless I was adding real value, and it took me a while to get the courage to believe it. And when I left, I wouldn’t say that I fully believed it. We all have that imposter syndrome, but I knew enough was enough. I knew that [Wall Street] was no longer the path, so I had to go and figure it out.

What are some of those practical steps that you took after you believed you could bet on yourself?

The first thing for me was giving myself financial flexibility to have time to figure it out. I knew when I left I didn’t have it all figured out. It would take me time to learn and figure out a new industry. I participated in the real estate space, but it wasn’t my day-to-day experience, so I had to change some things about my journey and mindset. Moving back home to Detroit gave me some more flexibility than living in New York and then saving enough money over those three years so I could have time to figure it out.

The second piece was ‘uncertainty breeds doubt’. So, I started making steps to create a plan to eliminate the uncertainty and to eliminate the doubt. I started bidding on RFPs for projects; I started making myself seen in projects in the city. I started being everywhere in the city and being a fixture, not just about real estate, but who else could I help? The more I spent time doing policy and civic service, the more I felt I had that ecosystem that would support me to do the work. I became a known commodity, so others began to believe I could do the work, and that gave me time to put the plan together.

It was a process and a journey. It took years to get the credibility for people to know I was serious about this work. I was committed about the work and I was going to be consistent about the work. So, it was putting that plan together that helped to eliminate some of my concern and doubt, which eliminated the fear.

How did your love for the game Monopoly influence your career and investment decisions?

Monopoly and Legos were the beginning blocks of my career. I still love Legos. I was building structures when I was three years old. I didn’t know what I was doing. I wasn’t trying to be an architect, but I liked building stuff. I like creating things. It was that imagination of initial creativity and entrepreneurial spirit. I liked winning in Monopoly. I don’t lose much in Monopoly; my daughter can beat me, but other than that, most people can’t beat me. My daughter is only 10, so she’s on a whole different path. Monopoly allowed me to play with different strategies of how to play that game, which taught me to be creative and flexible and employ different strategies to win and solve every problem.

There is no age too early to learn. Problem-solving, just like anything else, is a learned and enhanceable skill, so the earlier you start learning and solving problems, the better you get at it. People sometimes assume that things get handed to you at a certain point in your life. No, I’m just really good at solving a problem, and I can see a solution that others can’t. Not because I’m smarter. I have more practice. I can connect dots that you can’t see quite yet. And what you think is impossible; I know it’s a step in the road. My kids have learned about entrepreneurship from day one. They’ve always been in conference calls when I [had] a corporate job when I was doing mergers and acquisitions when I was buying and selling companies, which in many ways is another form of Monopoly. My oldest son was in the room listening to me negotiate. My daughter goes to the buildings and hears me talk about a capital stack. She hears me talk about rent, construction, and legal contracts. She doesn’t grasp everything, but she gets the gist, and there is something to be said about talking to the younger generation super early because if they digest it, [it will] become second nature to them.

What was the most significant lesson you learned from your merger and acquisition experience, particularly from the time that you lived overseas?

The biggest thing I learned from M&A was that the game is never over. There have been several deals that I’ve done in other countries. One of the most significant that I’ve done was by myself at a negotiation table in Amsterdam, and a massive issue popped up. I remember my business CEO telling me to pack up and leave. We had been there two or three weeks, I burned through millions of dollars and man-hours pulling this deal off, and I knew in my heart of hearts I could pull this off. But I felt like folks’ egos were getting away, so I had a decision to make: was I going to bet on myself or was I going to do what I was told? And I bet on myself – that we could figure out this problem. So, instead of telling everyone to leave, because it was going to take us 24 hours to get out anyway, I used that 24 hours to solve the problem. That always told me just because you said it doesn’t mean it’s right, and at times, you got to be willing to figure out if [it] was the right decision.

I would say the second thing is that in the course of an M&A deal, a deal can die five or six times before we get to the finish line. Every problem has a solution. Sometimes, the solution is just having to walk away, which I’ve had to do for real estate deals. But usually, every problem has a solution. I assume every problem I see in real estate is solvable. I don’t care if it’s financially related. I don’t care if it’s staffing-related. I don’t care if it’s because I got a burglary. I don’t care what it is. It’s never a solution I can’t solve, and that stems from two things. One, I think I’m talented, but two, I know I ain’t that talented, and I rest on the fact that I have an unbelievable faith in God. I could not do this by myself. It’s impossible. I am doing things I didn’t even know existed seven years ago, so clearly, I got more support and a higher power than I got talent.

Tell us about the current projects you are working on in Detroit.

We consider ourselves a creative pacemaker. Our goal is to honor the historical legacy of communities in which we invest in while bringing something very beautiful to it. We believe that we bring not only financial investment, we bring cultural investment through the arts, which is a big part of our projects. Currently, we have two projects under construction, and with our pipeline, we are on track to invest $70 to $80 million in the city of Detroit through our products alone. Based on the work that we’re doing, our impact in the city will be well over $100 million from a standing start in just under four years. We have a lot more to do from an impact perspective and creating an environment ecosystem for other developers’ businesses to survive and thrive.

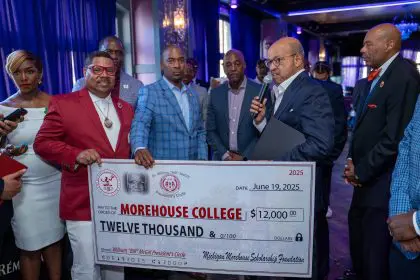

We also launched our first fund in Juneteenth of 2022, called EBIARA, in which we invest funds and make an investment into Black and Brown firms who are doing deals in the city of Detroit. Our pilot fund raised 11 million dollars and our goal was to stimulate $200 million of development activity. To date, in just over 15 months, we have committed $6 million worth of capital that will stimulate $200M worth of development activity. It just proves that there’s more to be done, there is work to be done to grow and scale Black and Brown development firms, and with the capital and the support that they need, they can be as big as any development firm in the country.

What advice would you give aspiring entrepreneurs looking to venture into real estate development or boutique management?

One, make sure you’re ready for this journey. It’s a roller coaster and not for the faint of heart. Make sure you’re willing to do whatever it takes to survive. Everyone wants to make entrepreneurship sound sexy. It ain’t necessarily easy. If it’s only about the money, find something else to do. You have to have a passion. You have to be committed to fighting through it when it all goes bad because there are always times when you feel like it all goes bad. Money won’t get you up in the morning when you feel like all goes bad, you have to have a deeper meaning.

Two, become an expert in your field. Nothing beats talent, time, and expertise, and if you combine that with your willingness to work harder than everybody else, you can be successful. But this ain’t for the faint of heart. There’s no get-rich-quick scheme and no TikTok algorithm. It’s nothing but hard work, dedication, and planting positive seeds in the universe and in your community that you will harvest later when you least expect it.