The Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina has long stood as a proud and resilient Indigenous community, recognized for its unique cultural identity and ongoing struggle for federal recognition. However, a lesser-known but equally significant aspect of their history is their deep-rooted connection to African Americans.

The Lumbee people are descendants of Europeans and freed/enslaved Africans, forming a rich and complex heritage that challenges conventional narratives about race and identity in America. This blending of cultures created a unique ethnic group that, while self-identifying as Indigenous, carries significant African ancestry.

Early beginnings: A cultural crossroads

In 1756, the General Assembly passed a law imposing a tax on all free Negroes, Mulattos, and Mestizos.” This required them to pay a tax based on their racial classification. This capitation tax remained in place until 1865, requiring them to pay it for 109 years.

On April 20, 1794, free African Americans in Marlboro County, South Carolina, petitioned the legislature to repeal this discriminatory tax. Signers included Richard Evins (Evans), Nathaniel Conbie (Cumbo), George Collins, Cudworth Oxendine, William Swett and many others. Some who supported the petition, such as Joseph Bass and Levi Gibson, were considered white.

Scuffletown, later known as Pembroke, North Carolina, became a refuge for these individuals fleeing South Carolina’s oppressive tax on free people of color.

African American folklore also links the Lumbee community to the Underground Railroad. One oral tradition tells of mixed-race children, the result of relationships between enslaved women and their enslavers, who were sent through the railroad until they arrived in Scuffletown. Their presence there was reportedly due to slave mistresses seeking to rid themselves of reminders of their husbands’ indiscretions.

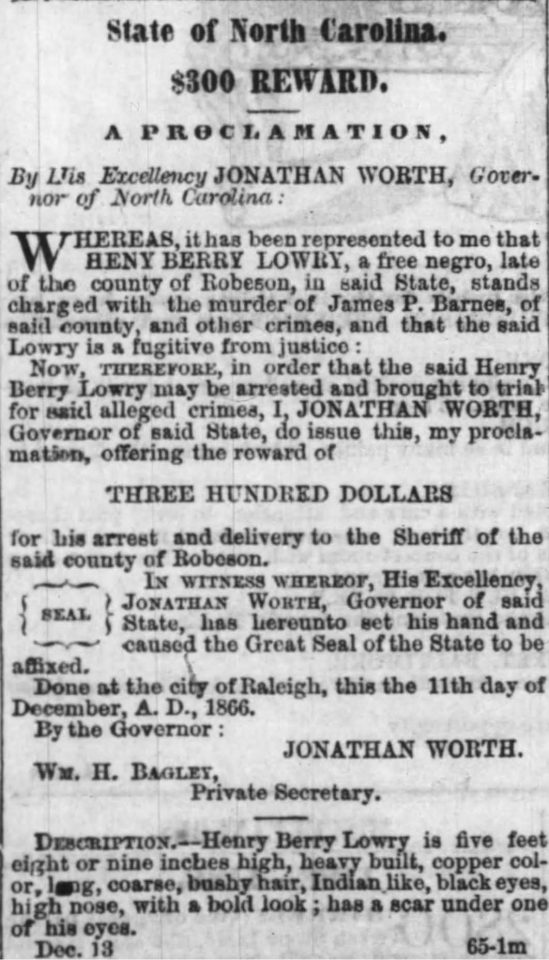

During the 1860s and 1870s, a notorious outlaw group terrorized Robeson County, garnering national attention. Newspapers and wanted ads described them as “Negroes.” Their leader, Henry Berry Lowry, gave an interview while imprisoned in Wilmington, North Carolina, in 1889, in which he described his ancestry as a mix of Portuguese and African instead of Indian.

Census records from the same era identified Lumbee ancestors as “mulattos.” In the 1800s US census, a “mulatto” was defined as someone of mixed African and European ancestry, typically considered to have at least some visible trace of African descent, and was first officially added as a category in the 1850 census; census takers were instructed to categorize individuals as mulatto based on their appearance, essentially judging their “degree of black blood” through visual observation.

Resistance and identity in a segregated south

Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, the Lumbees faced systemic racism and exclusion. Their ambiguous racial classification made it difficult for them to navigate a segregated society. While some Lumbee sought to distance themselves from their Black ancestry to gain social and legal recognition as an Indigenous group, others embraced their multiracial heritage.

During Reconstruction and the Jim Crow era, Lumbee people resisted racial discrimination and efforts to force them into Black schools and institutions. By the 1880s, they had become a significant voting bloc that sought to avoid classification as “Negro.”

The concept of Indian identity as distinct from African Americans gained traction in 1885 when North Carolina Democrats sought to impose Jim Crow laws. Hamilton McMillan, a Democrat from Robeson County, ran for the General Assembly and sought Lumbee votes by promising them a school and a historical identity.

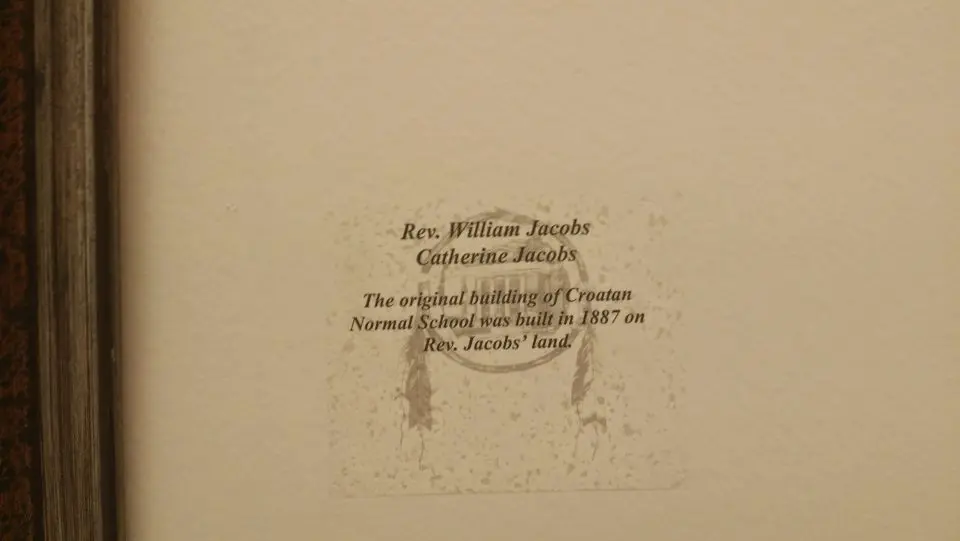

McMillan capitalized on the resentment among free African Americans, who disliked being forced into the same schools as formerly enslaved people. He helped pass a law allowing them to establish their own separate schools. The school established was called the Croatan Normal School (currently the University of North Carolina at Pembroke) to reinforce their identity, McMillan revised an existing historical narrative about Virginia Dare and the “Lost Colony” of Roanoke, claiming that the colonists had mixed with friendly Indigenous people, forming the ancestors of those living in colonial Robeson County. He named them “Croatan Indians.”

The Indian schedule in the 1800s census was a special section of the census that included additional questions about American Indians. The schedule was added to the general census and was usually located at the end of the county. There were no Indians listed in Robeson County until 1900 – after McMillian’s revisionist history.

White residents ridiculed the name, calling them “Cros” after Jim Crow, prompting the community to rename themselves “Cherokee Indians of Robeson County” in 1913, “Siouan Indians of Lumber River” in 1934-1935, and finally, “Lumbee Indians” in 1956, when the U.S. Congress granted them limited recognition. The latter name changes were partly due to opposition from federally recognized Cherokee and Sioux tribes, who lobbied against Lumbee efforts to use those names – and in later years have fought against their full federal recognition.

In the 1930s, the U.S. government attempted to classify individuals racially using tests such as the “comb test.” If a comb passed smoothly through a person’s hair, they could qualify as Indian; if not, they were classified as Negro. This practice divided many families along racial lines.

The battle for federal recognition and racial politics

When securing recognition under the Lumbee Act of 1956, the tribe agreed not to pursue financial benefits associated with federal recognition. However, in 1969, they renewed their efforts to obtain full federal status.

A major point of contention in their struggle for recognition has been their mixed-race ancestry. Some opponents have used their African lineage to challenge their Indigenous identity, reinforcing outdated ideas about racial purity in Native American identity. Historically, bills recognizing the Lumbee have passed in the House but stalled in the Senate, reportedly due to whispers that they are “African American.”

During the 2016, 2020, and 2024 presidential elections, Donald Trump’s campaign recognized the significance of Lumbee votes, aggressively courting the 55,000 members of the tribe. On January 23, 2025, President Trump issued a memo titled “Federal Recognition for the Lumbee Tribe.” While it gave the appearance of progress, it did not change the fundamental need for congressional approval. The executive order was largely symbolic.

Despite these political maneuvers, the Lumbees continue to assert their sovereignty, emphasizing that Indigenous identity is rooted in community, culture, and self-determination rather than racial purity.

In the era of DNA testing, younger Lumbee generations often express confusion when their results show no trace of Indigenous ancestry. This underscores the complexities of racial identity and how it is defined beyond genetics.

A legacy of strength and unity

Today, the Lumbees celebrate their rich heritage. Their history exemplifies the resilience of mixed-race communities that have thrived despite systemic efforts to erase or delegitimize their identities. Recognizing the Black presence in Lumbee history provides a fuller understanding of America’s racial complexity and honors all those who shaped this enduring legacy.

Robeson County and Pembroke today

Despite their rich cultural heritage, Robeson County and the town of Pembroke continue to face significant economic and social challenges. The county remains one of the most impoverished areas in North Carolina, with high unemployment rates, limited access to quality healthcare, and persistent educational disparities. Many Lumbee families struggle with generational poverty, and economic opportunities remain scarce, forcing many young people to leave in search of better prospects.

Pembroke, as the heart of Lumbee culture, is home to the University of North Carolina at Pembroke, which serves as a beacon of educational advancement for the community. However, the economic benefits of the university have not fully translated into widespread financial stability for residents. The town has also faced issues with infrastructure development, small business support, and crime, which continue to affect its overall growth and prosperity.

Community leaders and advocates are working to address these challenges through initiatives aimed at economic revitalization, cultural preservation, and improved access to education and healthcare. While progress has been slow, there is a continued effort to build a brighter future for Lumbee people and the broader Robeson County community.

The Lumbee story: A testament to Black and indigenous interconnectedness

At a time when discussions of racial and ethnic identity are more relevant than ever, the Lumbee story serves as a powerful reminder of the interconnectedness of Black and Indigenous histories in the United States. Their journey is one of survival, resistance, adaptation, and pride in a heritage that defies easy categorization.