BOSTON – A flash of heat still races through Deloris Lawhorn’s bloodstream when she thinks about how whites threw rocks at her family car when she rode through South Boston as a teenager in the 1970s. The harrowing incident left a permanent mark on her subconscious and soul, sort of like a tattoo. While she still avoids venturing into South Boston alone at night like it was a snake pit, she admits that the city has evolved.

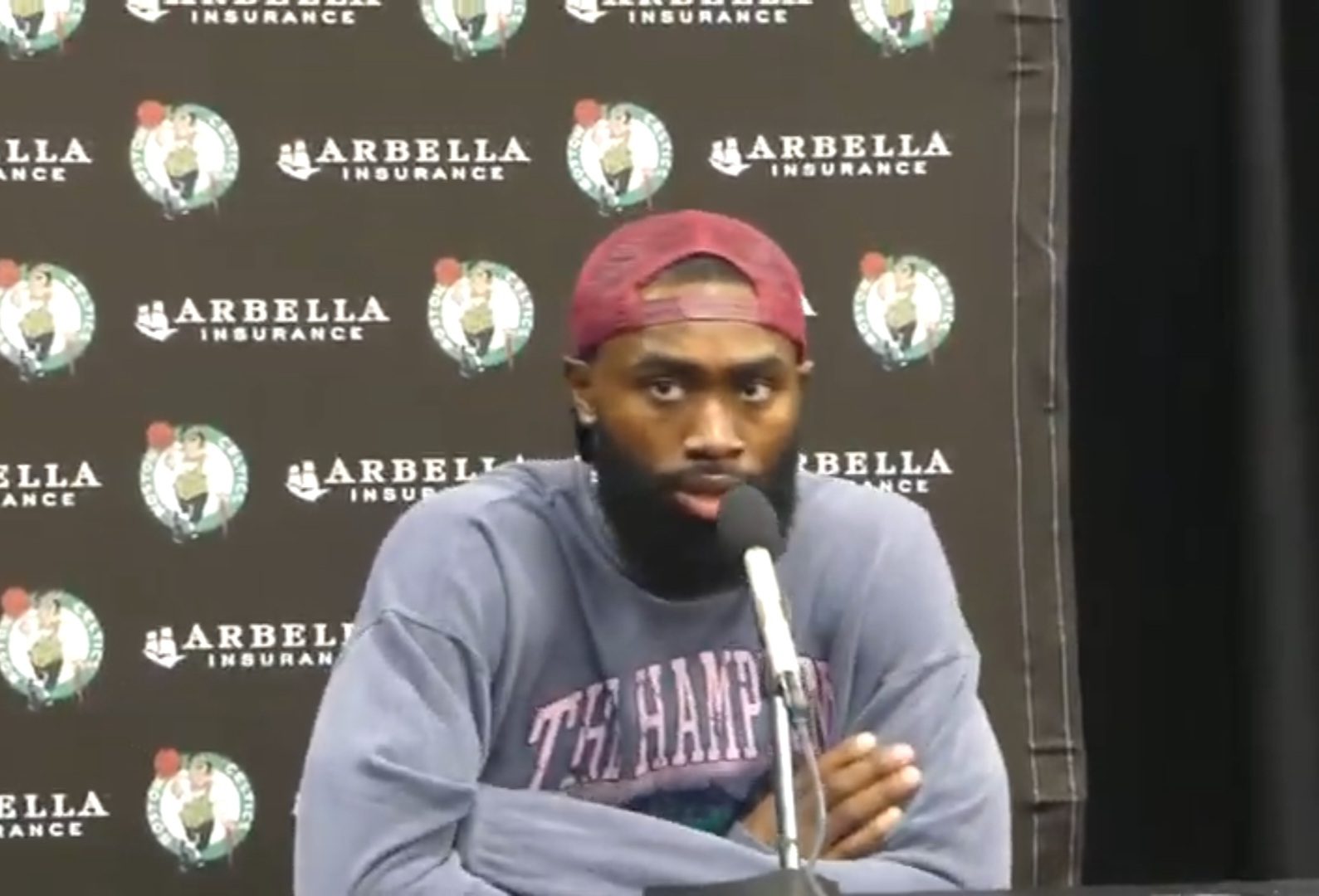

“I’m shocked. Right now we’re sitting in South Boston,” says the born and bred Bostonian as she prepares to lunch at the 101st National Urban League annual conference. “South Boston is the heart of the city that had all of the racial tension in the ’60s and ’70s. It was the have nots [poor whites] versus the inner city [Roxbury]. The city had built these Irish projects, and they were the ones who had the problems with the blacks, not the ‘lace-curtain’ Irish.”

Many urbanites across the country still cast a wary glance at the capital of New England. Despite its world-famous educational prowess — Harvard, MIT, Boston College, Northeastern University, etc. — Boston was oftentimes called the Mississippi of the North for its infamous racial intolerance. This was the city, mind you, whose residents even threw rocks at Sen. Edward Kennedy for having the gall to try to desegregate the city’s schools in the ’70s. This was the city that ran NBA legend Bill Russell out of town despite him being the most important ingredient in their long championship run. And the city’s baseball team, the Red Sox, was the very last organization to integrate and accept blacks on the squad.

As a result of that, a residue of resentment still lingers with some longtime residents despite the passage of time.

In fact, it has been 35 years since the National Urban League last held its conference in Boston. Some residents say the NUL was pretty much run out of the city back then, and the NUL refused to come back until now, protestations be damned.

Bizuayne Tesfaye understands completely. The Ethiopian-born, American citizen could not even have fathomed a large black gathering in South Boston, the site of the Boston Convention and Exibition Center where the National Urban League held its 101st conference. Even now, when the Associated Press photographer and his wife dine all over the city, he says that 95 percent of the time, they are the only blacks in the restaurants.

Still, the problems that Testaye had when he first moved into Boston from Africa 22 years ago were unforgettable. “I’d be on assignment in South Boston [as an example], the police always come up to me and ask, ‘What are you doing here?’ and they asked me, ‘Are you a local? Are you from South Boston?’ ” he says. But Testaye says the city is indeed climbing out of the dark ages. “It’s a big difference in the last 20 years. Big difference. I love Boston. As the years went by, I saw more and more integration.”

Not so fast, says Doreen Wade. “I disagree wholeheartedly. Let’s put it like this: race relations in Boston are still bad. We have no radio station. We have one lone newspaper. You have black businesses that are being bought up by white businesses. It is really sad that they spent a whole week portraying Boston’s race relations as better than it really is,” she says of local politicians who spoke at the NUL convention.

Tiffany Probasko, a native of Portland, Ore., is accustomed to the racial percentages that are present in Boston. But Portland had none of the white racist violence so attached to Boston’s modern past. And she was warned when she first moved where to go in the city and when.

“I was told not to go to South Boston,” she says. “There are still parts of South Boston that I would not go to today. Especially at night. Because you might get an old-school person who might want to maintain the old status quo in a violent way.”

And blacks are staying out of the Boston business district, says Pam Perry of Detroit. Coming from such a predominantly black city as Motown, the lack of people of color in downtown Boston was very disturbing to her. “We were actually looking for black people. The only ones we saw were homeless black people. We didn’t even see any people of color.”

Which makes you wonder just how much progress Boston has really made after all.

Though Lawhorn prefers the rich cultural outlay of Washington, D.C., and Chicago — she lived in each city for seven years — she says Boston is steadily improving, even if at a glacial pace.

“I really had post-traumatic stress,” Lawhorn admits from having gangs of whites throwing stones at her as a child. “And despite my friend telling me ‘Deloris, there are white people who live in Roxbury and there are blacks who live in South Boston today,’ I can’t conceive how black people can live in South Boston. Like, how did it evolve that much? I never thought that could happen.”

–terry shropshire