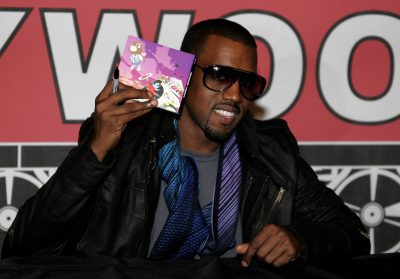

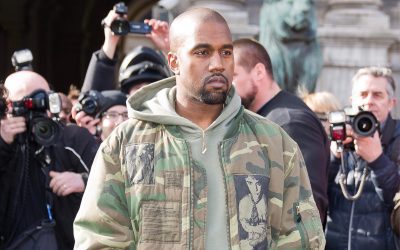

Following a late night Facetime debate with my grandmother last night, I found myself on YouTube seeking snippets of artist Kanye West’s politically charged post-Hurricane Katrina 2005 pronouncement that sitting president “George Bush doesn’t care about black people.”

During a celebrity-led telethon set to raise funds for Americans displaced during the cataclysmic wash that might have been prevented had proper local and national attention been dispatched to New Orleans’ primarily poor parishes that would be impacted by the rough waters, West stands beside actor and comedian Michael Myers awaiting his chance to speak. Both men present properly dour dispositions during the broadcast. Both appear moved, saddened and heartbroken for the outcome of the storm that had, at that point, claimed hundreds of lives. Still, beside Myers, West appears to be a man charged with a higher calling. He isn’t simply there to ask people for money. He has an agenda. He has something to say and it’s clear, looking at his body language — fists in pockets, eyes straight ahead, a tightened jaw, an air of defiance in his stance — that he is going to use his spotlight to make a claim that debunks all politically correct acumen, yet gives voice to thousands of viewers who supported and echoed his sentiments from their homes with “Right on!” and “He’s telling the truth!”

Following Myers’ seemingly scripted statement, West goes rogue. With his chest poked out like a boy beginning his Easter speech for his grandmother or some contingency of expectant old black souls in the front pews, he starts, “I hate the way they portray us in the media. If you see a black family, it says they’re looting. If you see a white family, it says they’re looking for food. And you know it’s been five days, because most of the people are black” to express disdain at what had been deemed racialized media coverage of events following the hurricane and a lack of adequate services from the government in the wake of the storm. After admitting that he’s also guilty of turning a blind eye, West makes a statement that would put him center stage in an ongoing dialogue about who was truly impacted by the lack of services before, during and after the storm and why. West gets to his raison d’etre firing, “George Bush doesn’t care about black people.” The accusation is followed by pregnant silence between West and Myers, a confused stare from Myers and an awkward emergency transition to comedian Chris Tucker, who stutters into his speech.

I was led to view West’s 2005 diatribe because the video-call debate I’d been engaging in with my grandmother, who was at home in New York while I waited outside of an Atlanta Waffle House for a double order of scattered and covered hash browns, began with my MSNBC-watching grandmother stating, “You know they haven’t released the name of that officer who killed Michael Brown? All these days after that boy was killed and no name …”

In most of our debates, I play devil’s advocate to her Rachel-Maddow-Melissa Harris-Perry-infused outspoken liberal opinions that provide an accurate soundtrack of most of our dinner conversations through the decades of my life (it’s just how we get down). Therefore, I stared into her eager eyes through my iPhone and shot back, “I don’t care who killed Michael Brown. Why does it matter?” I knew full well this would lead to disapproval and choice words, and she didn’t disappoint. She shared what all of America has been saying on social media over the last few days — leaving the shooting officer’s name out of the dialogue about Brown’s murder is about protecting the officer, where Brown had no protection. Further, it’s about cops getting a virtual “go get-em” card to wreak havoc on young black males in the ‘hood with little recourse, reaction or reprimand. She continued with a list of facts from the case that further implicate a system-wide demand to protect police officers — tear gas, rubber bullets, journalists being arrested, witnesses being ignored, officers refusing to provide names and badge numbers upon request. Again, I was faced with her anxious eyes. She wanted a response. Surely, I would rescind my initial comment about not wanting a name following her knowledgeable support.

I began to calculate a response to defend a position I really only concocted to engage a more interesting dialogue about what people are calling “the situation in Ferguson.” What I found in my pondering and later my defense of my initial statement is that I honestly don’t care who killed Brown. And I mean that in the highest order or needs. In a lower order of needs, of course the public deserves to know who gunned down an unarmed human. That’s pretty obvious. But in a high order, where more specific adjectives are added to the basic circumstance of one human killing another and justice being sought in the wake of said incident, a name is a flimsy and pointless endeavor as we begin to really talk about what led to blood that day in Missouri.

We are not simply talking about a human being killed. We are talking about a man, a young black man, a black man in a marginalized community, being gunned down with no provocation (it has been confirmed that he was unarmed) by an officer who works under taxpayer generated funds with orders “to protect and to serve” those in the community to which he or she was assigned. Considering these attributes, in a high order of needs seeking a true discussion that could actually lead to a thoughtful understanding of the nature of the crime and thus lead to radical change (who am I kidding?), I ask what led to this occurrence. Not why it happened on that day, but knowing “it” consistently happens everyday, I ponder what’s actually led to decades and centuries of hundreds and thousands of unarmed black men (all with names) being murdered by police officers (all with names).

That brought me to West’s statement about Bush not caring about black people. I press further and change his words to what he really meant that day, to what he should’ve said that day, the higher order of needs of his claim. In synecdochic language, the nation has no love for black people. More directly, in reference to the Brown massacre, the nation hates black males. And when I say that, it becomes more clear that the name of Brown’s murderer is minor, because what really killed Brown extends far beyond one person, one force, one community, and reveals a system that is in place that devalues the lives of African American boys from the moment they are born. From the very hospitals where their mothers push them into existence to the graveyards where they will surely someday lay their heads, few-to-no services in marginalized communities where most commonly minority populations reside, provide adequate services that show an ethos that respects black males in any fashion. Moreover, in this country, where are the worst hospitals? The worst schools? The worst day care centers? The worst grocery stores? The worst libraries? The worst police precincts? The worst fire houses? The worst parks? The worst courts? The worst streets? The worst highways? The worst graveyards? The worst everything? Anything? Even graveyards… Now, I realize how charged the word “worst” may fall on the ears of people who reside and work in the very communities where the worst services are rendered. And I surely respect those who work in the trenches to make the best of the resources provided, but latter in the former statement is my point altogether. Those well-meaning teachers and doctors and lawyers and grocers and restaurant owners are working to make the “best of” what’s available, which is often near nothing. And it’s not just because these are poor neighborhoods. It’s because these are often poor, black neighborhoods. As Brooklyn-born Spike Lee pointed out in a recent statement about gentrification in New York, “… why does it take an influx of white New Yorkers in the South Bronx, in Harlem, in Bed Stuy, in Crown Heights for the facilities to get better? The garbage wasn’t picked up every motherf*****’ day when I was living in 165 Washington Park. P.S. 20 was not good. P.S. 11. Rothschild 294. The police weren’t around. When you see white mothers pushing their babies in strollers, three o’clock in the morning on 125th Street, that must tell you something…”

But, I digress. Back to the matter of the kinds of services rendered in these communities, I contend that beside well-meaning service workers are interestingly (and seemingly strategically) placed people who consciously, subconsciously, and often directly abhor the people in the communities where they work. To some teachers. To some lawyers. To some doctors. The some police officers. The very sight of a black male–boy or man–presents a preset psychological response of lowered expectations and thus treatment. He is dumb. He is dirty. He is lazy. He is a killer. A thief. A rapist. He is no one. He is unteachable. He is unreachable. He is unsalvageable. Unsavable. Savage. This set of whispers mushrooms into an invisible cloud of words that fill the space between a black male and all around him (sometimes including his own people) at any given moment. Often even the person in service doesn’t realize he/she feels this way … not until the teacher encourages him to cheat on an exam, the doctor refuses to see him because he can’t pay his medical bill, the judge gives him double time for a crack cocaine conviction that would send a white man dealing cocaine just a neighborhood away home to his family in half the time. Not until several shots are fired into the body of an unarmed teenager one week away from college.

Who cares who killed Michael Brown? That name has little significance to me. What’s more significant is why that person pulled that trigger. What made him or her fire and fire and fire and fire at the back and then the chest of a chubby baby boy with his hands in the air? That’s what I want to know. That’s what you should want to know. That’s the only way we will change anything because the true nature of this crime is in the system — not the murderer. Until we change the system, another day, another death.

Ezell Ford, Los Angeles, California / Aug. 11.

John Crawford, Beavercreek, Ohio / Aug. 5.

Eric Garner, Staten Island, New York / July 17.

Who killed them?

–Calaya Michelle Reid @blackwritergonerogue