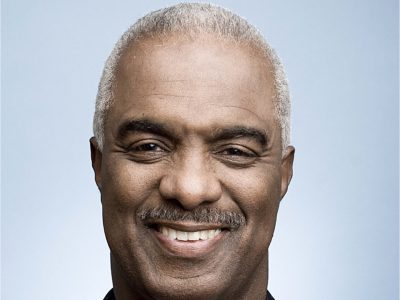

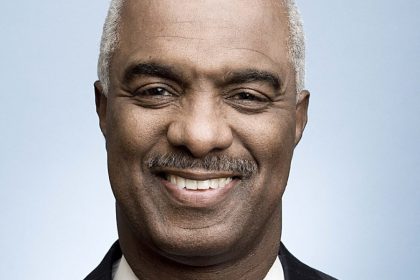

In a time of deepening political divisions, Robert Traynham takes the helm of the Faith & Politics Institute with a rare mix of diplomacy and conviction. As President and CEO, effective February 17, 2025, he brings a perspective shaped by his journey from Cheney University, the nation’s first historically Black college, to Georgetown University, where he teaches leadership.

Tasked with leading the institute’s Congressional Civil Rights Pilgrimage to Alabama on the 60th anniversary of Bloody Sunday, Traynham steps into a role that demands both strategic focus and moral clarity. A firm believer in listening before leading, he studies viewpoints across the political spectrum—whether in newsrooms or Walmart aisles.

His approach, blending academic insight with everyday realities, reflects his belief that leadership is about more than titles. At Georgetown, he teaches that true leadership begins with moral integrity. Now, as he steps into this new role, that philosophy faces its greatest test.

What made you choose to be a leader at the Faith and Politics Institute?

Thank you for that question, Munson. And I’m gonna back up for a second, I believe that we’re all leaders. I believe that we’re all CEOs. I don’t care if you have the title of cleaning up after us, or washing our dishes, each and every one of us is a leader.

I’ve always had this moment. I’ve always known that I would love to be able to help execute a vision, help move the needle, help have impact. It doesn’t matter what organization it is. I mean, it has, obviously it has to align to my values. But what really matters is how can I move the needle? How can I have impact? And how can I give back? I truly stand on the shoulders of people that look like you and I, that have struggled for years and years that never had the title of CEO or leader, although they were.

The Faith and Politics Institute came knocking on my door, I really wasn’t looking per se. But they came knocking on my door and said, “Hey, listen! Based on your feedback that you’ve given us over the last couple of years based on your impact, let’s have a conversation.”

And I just love that type of relationship where both sides, it’s almost like a relationship where both sides come to the table and says, “Hey, I kind of like you. Do you like me? Because if so, let’s figure this out together.”

What would you suggest leaders align themselves with regarding being an empathetic listener in your organization?

Yeah, so let me answer that question a little bit differently, because you know, one of my hats that I wear is, I teach leadership at Georgetown University in Washington, DC. So I’ve thought a lot about this, and I really teach this. First and foremost, it is a moral compass. I believe we all have one.

Now I think the question becomes is, whether or not you act on it. How often do you act on that? But we all have a moral compass, and for me it is from leading from within. And what do I mean by that, Munson, is doing the right thing when no one else is looking, and what I mean by that is that do you return the shopping cart after the supermarket, or just leave it in the parking lot?

Do you clean up after yourself? When else do you say thank you? Do you look the person in the eye that perhaps maybe is asking for money on the street, and says, “Here’s how I can help you.”

So it is leading from within and doing the right thing when no one else is looking. It’s not about the accolades. That’s number one. Number two in terms of the empathy that you mentioned, it is what? What is that? It’s listening.

It’s meeting people where they are and showing up in an authentic way by saying, “Listen, it doesn’t matter if I’m wearing a coat and tie, or you know, if I have a house and a car, what matters is is that you are hurting, or that you have an issue, or that you have something that you want to run past me, that I’m giving you my full attention, that I’m giving you the dignity and respect to listen to whatever you have to say, and giving you authentic feedback.”

And so that means listening and showing up in a way that your moral compass tells you how to how to do that, and I can talk more about that. But hopefully, that answers your question a little bit.

What characteristics do CEOs often miss that can change and increase the morale of an organization?

It’s a couple of things, Munson, the feedback that I’ve gotten over the years is “Robert, you know you actually listen. When we sit down and have a conversation with you, I turn my phone off. I put it on silent. I literally am giving you that eye contact in that respect. And then I’m following up.”

And that shows that I’m listening to obviously whatever the conversation is. I’m also authentic and telling the truth. I believe that one of the characteristics, one of the bad characteristics of a leader is that you always say yes to everything. It’s actually easy to say yes to a lot of things. And obviously you’re trying to appease people. I get that.

But the reality is that when you say no, or if you say “that’s a really good idea, but I’m not sure that’s where we want to go, and here’s why.” And the reason why I say that is because it’s the relentless and the ruthless prioritization on behalf of the organization by saying no, you’re actually saying yes to other priorities. And so one, it actually gives a lot of priority to the staff.

Two, hopefully, it creates a lot of space to move that clutter out of the way and three, it brings a lot of clarity to you and to the team. Now, that isn’t something that a lot of people like to hear.

I get that most people want to hear yes to a lot of their ideas, but what I’ve heard is the feedback that I’ve gotten is “thank you for telling me the truth, thank you for listening to me, and thank you for being real,” because it just manages my expectations.

That is the one characteristic, quite frankly, that’s overlooked is listening, telling the truth and being authentic when you say yes, and when you say no.

How should young CEOs align and create goals and benchmarks throughout the year?

I’ll answer this question this way, a lot of people like the title of President and CEO, or chairman of the board, you know, who doesn’t want that title? But if you’re driven by that, you’re in the wrong business because you’re really driven by your ego, and you’re driven by ambition. And that’s a recipe for failure.

If, in fact, you prioritize and says, “Listen, I’m aligned with this organization. This is something that I fundamentally believe in. What are the 3 specific things that I need to accomplish this week?” One, two this year, and three, maybe 2 to 5 years from now.

What is the immediate goal? What is the medium goal? And what is the long term goal and focus on those 3 things where you’re managing down to your staff. You’re managing up to your board, or whomever you report into. But you’re also managing yourself, because at the end of the day. In my view, being a CEO is running a marathon.

You’re not running a sprint. You’re running a marathon, and so it’s 26.2 miles. This is not 6 miles. Anyone knows who runs marathons. You have to pace yourself, because if you don’t pace yourself what you get burnt out very quickly, and then you start hyperventilating. You start gasping for air, and you know what happened, because your body is shutting down.

Mentally, you start to shut down, and then you’re bored and your staff are like, “well, what is the focus here? He’s all over the map. I don’t know what the priorities are.” Hence, when I go back to my point around saying no, and also saying yes.

Those 3 specific goals, the short term, the medium goal, and a long term goal, are the most important. Now to your second part of your question, how do you measure that success?

There needs to be key milestones and deliverables where you’re setting benchmarks around, how you’re measuring their success around the medium, the long and the short term goals, and actually be honest with yourself. Candidly, and this goes back to my authentic leadership styles, telling the truth with yourself. You know what? I really screwed that one up, this was a stretch goal we didn’t get there.

I am being honest with myself and also with my team and also with my board, we set this goal. We got here. We didn’t meet it. But let’s talk about why we didn’t meet it. We didn’t meet it, because, frankly, I didn’t shoot high enough, or whatever the case may be, so, being vulnerable, being honest and authentic.

With respect to your key, milestones and deliverables, I actually think, is one of the most key characteristics that a leader should have.

Why is it important for you to share and educate future leaders while teaching at Georgetown?

I have a sneaky suspicion, and it’s twofold. One, most people who sit in the seat do not have like some job description, or like a manual that says, “Do this, do that every single day.” That typically doesn’t happen. A lot of this is a lot of feel. It’s a lot of feedback from your board. It’s a lot of feedback, quite frankly, just your own common sense. You have to figure it out on your own right.

And my second theory is that people that do not look like you and I, who historically go to an Ivy League school or went to an Ivy League school, or perhaps maybe have their father or their grandfather as legacy people that were CEOs, they actually have a role model. They have someone that they could actually look to, or perhaps maybe get advice from.

Most of the time, people that look like you and I don’t have that. We just simply don’t have that. So, in my view, I have a responsibility. I have a fundamental responsibility for people that look like you and I, but also any marginalized community. And sometimes that’s even just the working poor where I have to say, “Listen, I taught myself how to fish.”

I have a moral responsibility to teach you how to fish, too, and I’m not suggesting that you need to do it my way all the time, or what I am suggesting is that you just take a look at how I do it, and then you find your own rhythm. You find your own way to do this, but these are some of the fundamentals that you may want to think about when you sit into this seat.

So, in other words, I just have a very strong obligation, in my view and responsibility, to give back and to teach people how to fish, who, quite frankly, just don’t have those resources, or didn’t have those resources.

What are you seeing in the marketplace as business leaders need to future-proof themselves?

I view it as almost like walking through a landmine with a whole bunch of booby traps, and you don’t know where the booby traps are. So you have to generally kind of walk, and what I mean by that is that, look here, we are in 2025. The world has changed in literally the last 5 months since the Presidential election.

We can see that unfolding as you and I speak right, but also here domestically, and we don’t have to go into all the politics, but we know that the current leadership is going in a different direction. And what does that look like for DEI? What does that look like for the economy? What does that look like for? I mean, you just going down the list?

As a CEO one you have to maintain, you’re true to the mission of the organization, but you also need to navigate those booby traps as best as you can. But you also need to lead and to manage your staff, and in my case, as running a nonprofit, also, donors who had their own feelings and thoughts around around the current political winds.

There’s a lot of needles that you have to thread. And what I also tell people is that it’s okay to fail. Give yourself that grace. Give yourself that ability. When you’re running the marathon to slow down a little bit, you may fall through no fault of your own. You may fall, but the question is, how do you get up? And how do you recognize that?

That I fell and acknowledge that and keep moving forward. That’s a key piece of this is, it’s okay to stumble a little bit. But the real question is, when you stumble, how do you get up and acknowledge that, and move forward and learn from that.

How do you stay sharp and continue to be a life learner?

I’m going to go a little kind of lowbrow with you, and then a little highbrow. First a lowbrow, I love listening to other people’s conversations. I love sitting on an airplane or waiting for my flight at the airport, or frankly at Walmart, or wherever, and listening to other people. And frankly, what I’m listening for is their struggles around, “You know what, honey we can’t afford this refrigerator.

We got to put this back,” or “You know what? Let’s try to get it cheaper option as opposed to more expensive one,” because what I’m hearing is anecdotally their struggles, I’m hearing and seeing it firsthand. So that’s something that I’m extremely sensitive to. That’s a little bit more of the lowbrow.

I just enjoy being a fly on the wall and kind of metaphorically walking through other people’s shoes. The highbrow is, I read a lot. So in the morning I am fortunate that I’m naturally curious. I listen to a couple of podcasts in the morning. I read CNN, New York Times, Fox, the Weekly Standard.

I also read a healthy dose of the far right media, and also a healthy dose of the far left media, and I do that for 2 reasons. One, I recognize that we are in a divided country right now, and there are a lot of people that read one side. And I want to make sure that I understand both sides of a particular issue. So that’s one.

Two, I actually surround myself, I purposely surround myself with people that think differently than me. I do not want to be in an echo chamber, where I’m only getting the information that I’m used to right. That’s why, the day after the election I wasn’t 100% surprised that Vice President Harris lost.

The reason why I say that is because some members of my family, some of my friends, I purposely listened to their part of the conversation in the lead up to the election around their own thoughts and values around where this country was going, and quite frankly, it was very divided.

I just knew that going into the election Booth, and I wasn’t pleasantly surprised when I woke up and heard the news that President-elect Trump became President Trump. My point is is that I purposely do not stay in one lane. I deliberately, intellectually try to go in different lanes, so I’m hearing various parts of the conversation which, by the way to give you a prime example.

It could be Valentine’s Day. But there may be 2 interpretations of that, depending on who you’re talking to? So I like to listen to both sides.

Why is curiosity so important as a leader?

Because hopefully, you’re learning a different perspective or a different side of a view that you may have not have heard before. Hopefully, through deductive listening, you’re learning yourself.

“Oh, I never thought about that. Maybe I should think about how I look at this issue,” or “It’s fascinating. I’ve never been to Nebraska before. But now, hearing from Nebraskans, I want to think about programming that directly affects them, and other people that live in parts of Nebraska,” or “I am a product of an HBCU historically Black College University. I’ve never been to an Ivy League school meeting academically, but listening to their perspective, I have a different point of view.”

That constant thirst for learning candidly, that constant thirst to be relevant in the conversation, and that constant thirst in my view, to not be surprised. Again, I go back to the Presidential election, listening and asking questions from another point of view. I have to say, usually I’m not surprised now.

I could be miffed about something, but because I’m constantly listening and asking questions, I’m typically not surprised when it comes to most events.

What myths would you want to dispel about running and being a CEO of a nonprofit?

Two things. One, it’s hard, you have. There’s a lot of masters that you have to serve your board of directors, your donors. It’s not easy per se. Nor should it be. The first thing is that, in most incidences the CEO has got 5 or 6 different conversations going on in their head, based on the board based on donors based on the external environment.

They’re constantly having to navigate that so it may look like this CEO is vacillating. It may look like the CEO is flip-flopping, maybe, and maybe that’s on purpose. So there’s a method or rhyme behind that right? That’s the first misnomer. The second one that I would say is that it can be a lot of fun when you and the mission are aligned, and so, therefore, getting up to work is not a burden.

It’s more of, it’s almost like being a family member ahead of the family member, where you know I love my family, and I want to do this. And here are the reasons why, I hear a lot of times a lot of CEOs say, “Well, this is the most loneliest job,” or “You know I never wanted this.” I don’t feel that way at all, in fact, quite the opposite.

I’m invigorated by this work, and I do so because it goes back to me being aligned to the mission, and also just being naturally curious.

How did you bring your previous experiences into your current leadership role?

I would say, being my authentic self. First and foremost, I am authentically black. I am a product of an HBCU, so that is my lived experience, and I will always carry that into the day I die.

I speak up around a wrong. I will offer my perspective if it’s appropriate. And so I carry that throughout all of, I’ve carried that throughout all of my jobs to offer that perspective and that uniqueness. I would say to your viewers out there, be your authentic self. Don’t be afraid of that. You have to always be professional, but always show up and give your perspective when it’s relevant to the conversation.

That’s been my ethos throughout all of my jobs is, how can I contribute? What is my impact? And knowing, fortunately, I think honestly, even if I didn’t look the way I look, I actually think I would be a perfectionist, regardless, but because of the way I look, I set the bar high for myself, and the reason why is because my grandparents and my parents always set the bar high for me always.

I know nothing less but to give it my all, but then another 15 to 20%. So that’s just that to me, that’s just something that is innate in me that, what I’m trying to say is having a high work ethic, being a perfectionist and being not hard on myself, because I’m kind to myself, but also just having that high bar has really served me very well.

Why did you choose to attend an HBCU, and what did you gain from that experience?

I went to Cheney University in Cheney, PA. The first HBCU in the country. In 1837, just outside of Philadelphia. I grew up just outside of Philadelphia. So it’s about 45 min away from where I grew up.

I chose an HBCU for a lot of reasons. One, I was fortunate. When I grew up in the suburbs of Philadelphia, we were one of the rare African Americans in our neighborhood. My parents moved to an integrated neighborhood in 1970s.

I was usually the only, or maybe one of the few African Americans in my school. I wanted that authentically black experience because I didn’t have that outside my family. I didn’t have that in a school setting, so I was attracted to that. I was very much attracted to that.

I’ve been fortunate. I got my master’s degree from a predominantly white school and my PhD from a predominantly white school, but there is nothing like an HBCU experience. The class sizes are very small. The professors, I genuinely became friends with them. They were my mentors.

They were my friends, they were my! They pushed me to limits that I didn’t know I could be pushed before. I learned or became much more in tune with my history and my role in it. As African Americans I learned about African American entrepreneurs. I learned about the Chicago defender. I learned about the great migration from the South.

I mean just things that I didn’t learn in elementary school and junior high school. I had a unique appreciation for that.

The other thing that I learned, too, that actually, now, resilience that I still carry through throughout all of my jobs, giving a unique perspective on the African American experience when appropriate.

And also, the other thing that an HBCU taught me was an unabashed love for this country, but with one caveat. But our history and our impact is and was unique. And so, making sure that that is heard throughout corporate America is incredible, because oftentimes it’s not, is often. It’s something that I bring for my HBCU experience.

I would not trade it for anything in the world. I’m grateful to going to another majority school for my PhD and masters. But I would not trade going to an HBCU. It actually was transformational in my life, very much so.

Why is it important to achieve advanced degrees in today’s professional landscape?

I think, first and foremost, I want to be really personal. For a moment I got my master’s and my PhD from me for my own personal growth from my own, because I’m just naturally curious. I wanted that for myself. However, I would also say that for the young person out there that may be watching this, it’s just a wonderful growth experience for you.

It’s just wonderful to stretch and to learn so much more. I learned how to structure my thoughts in a very concise way. I became a better writer when I got my advanced degrees, because I had to write a lot, and my writing just got better over and over and over again.

My public speaking skills, became even more sharper, the more educated I became, and the more experiences that I had to be able to do that in grad school, my ability quite frankly to be able to hold my own intellectually. I’m not suggesting that I’m the smartest person in the room. I’m not.

I wouldn’t say that, but what I will say is that if I know what I’m talking about, I am not afraid to say it and say it in a very constructive way. What I also honed my skills on in graduate school was a point counterpoint. So most people would know this in any professional setting, but mainly in white collar settings, is there’s someone else that’s just as smart as you, that has a different point of view.

So how do you argue? How do you go back and forth in an intellectual point counterpoint where you’re making your point, and the other person is making their point, and you meet somewhere in the middle as opposed to becoming emotional and raising your voice, and it’s becoming very much a different conversation.

My point is, is getting advanced degrees, at least for me, helped me to make rational arguments that were thought provoking, that were substantive, that were never emotional.

There’s a difference there, because, as you may know, at least, I can speak for me. I’m very sensitive to raising my voice. I don’t think I have the liberty to raise my voice in white collar settings.

I don’t think I have the liberty to get angry. Fortunately, I’m a pretty low key, guy, but it’s just different for people that look like you and I as opposed to someone else when they raise their voice in the workplace.