Nearly 800,000 Americans experience a stroke each year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, making it a leading cause of long-term disability in the United States. Behind this statistic lies a pressing question for survivors and their families: is full recovery possible?

The answer is nuanced and deeply personal, depending on multiple factors that influence each survivor’s recovery journey. While some individuals regain nearly all their pre-stroke abilities, others face lasting challenges that require ongoing adaptation and support.

The science behind stroke recovery

A stroke occurs when blood flow to part of the brain is interrupted, either by a blockage (ischemic stroke) or a ruptured blood vessel (hemorrhagic stroke). Within minutes, brain cells deprived of oxygen begin to die, potentially affecting functions controlled by that area of the brain.

The brain possesses a remarkable ability called neuroplasticity—its capacity to reorganize neural pathways, form new connections, and adapt following injury. This biological mechanism underpins recovery, allowing intact areas of the brain to potentially take over functions previously managed by damaged regions.

Research has revealed that the recovery timeline typically involves several phases. The most rapid improvements generally occur within the first three to six months, followed by a slower but still significant recovery period that can extend for years after the initial event. This understanding has transformed how medical professionals approach rehabilitation, emphasizing early intervention while recognizing that improvement remains possible long after traditional recovery windows.

5 Factors that influence recovery outcomes

Several key elements determine how fully and quickly someone might recover from a stroke:

- Severity and location of the brain injury – The extent and precise location of brain damage fundamentally shapes recovery potential. Smaller strokes affecting non-critical areas may allow for nearly complete recovery, while extensive damage to regions controlling essential functions like speech or movement presents greater challenges. Left-hemisphere strokes often affect language abilities, while right-hemisphere damage typically impacts spatial awareness and attention. Strokes affecting the brainstem, which controls basic life functions, generally have more severe consequences than those confined to the cerebral cortex.

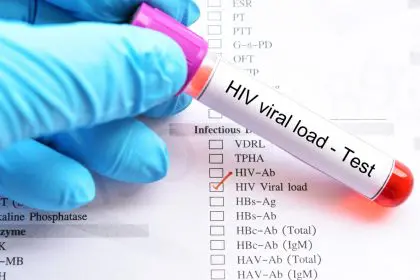

- Speed of initial treatment – “Time is brain” remains the guiding principle in stroke care. Clot-busting medications like tPA (tissue plasminogen activator) must be administered within 4.5 hours of symptom onset for ischemic strokes, while surgical interventions for certain cases now extend to 24 hours with advanced imaging. Faster treatment dramatically improves outcomes by limiting the extent of brain tissue death. Each minute delay in treating a large-vessel ischemic stroke results in the loss of approximately 1.9 million neurons, underscoring why immediate emergency response remains crucial.

- Age and pre-stroke health – Younger patients typically demonstrate greater recovery capacity due to enhanced neuroplasticity and fewer complicating health factors. Preexisting conditions like diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease can complicate recovery by impairing circulation and healing mechanisms. However, age alone should never determine rehabilitation intensity—many older adults achieve remarkable recoveries with proper support and commitment to therapy.

- Intensity and timing of rehabilitation – Rehabilitation approaches beginning within 24-48 hours after medical stabilization yield substantially better outcomes than delayed therapy. High-intensity, frequent therapy sessions targeting specific functions show greater benefits than less rigorous approaches. Studies demonstrate that additional therapy hours correlate with improved functional outcomes, with some research suggesting that doubling standard therapy time can significantly enhance recovery rates.

- Psychological and social support – Mental health profoundly influences physical recovery. Depression affects approximately one-third of stroke survivors and can significantly impair rehabilitation engagement and progress when left untreated. Strong social networks providing emotional support and practical assistance correlate with better recovery outcomes. Family involvement in the rehabilitation process enhances both motivation and practical carryover of skills into daily life.

Types of recovery possible after stroke

Recovery manifests differently depending on the specific functions affected:

Motor function recovery often progresses from initial flaccidity (complete limpness) through stages of increasing coordination and strength. While complete restoration of pre-stroke movement occurs for some, others develop compensatory techniques that allow functional independence despite residual weakness or coordination challenges. Advanced therapies including constraint-induced movement therapy, robotic assistance, and functional electrical stimulation have expanded recovery possibilities beyond what was previously considered achievable.

Speech and language recovery depends on the type of communication impairment. Aphasia (language processing difficulties) shows different recovery patterns than dysarthria (muscle-based speech production problems). Intensive speech therapy starting in the acute phase demonstrates significantly better outcomes than delayed intervention. Even those with severe initial language deficits sometimes achieve functional communication through dedicated therapy and communication aids.

Cognitive function recovery including memory, attention, problem-solving, and executive function may follow different trajectories than physical recovery. Cognitive rehabilitation employing specialized exercises and real-world applications can substantially improve mental processing and functional independence. Compensatory strategies often play a crucial role when certain cognitive abilities remain affected.

Breaking down what “full recovery” truly means

The concept of “full recovery” requires clarification, as it holds different meanings across medical, functional, and personal contexts:

Medical recovery focuses on measurable neurological improvement and stabilization of the condition to prevent recurrence. By this definition, many stroke survivors achieve substantial recovery, with brain imaging sometimes showing remarkable neural reorganization.

Functional recovery centers on regaining independence in daily activities like self-care, mobility, and communication. Studies suggest approximately 10% of stroke survivors recover almost completely, while 25% recover with minor impairments. Another 40% experience moderate to severe impairments requiring special care, with 10% requiring long-term care facility placement. About 15% die shortly after the stroke.

Personal recovery encompasses individual goals, life satisfaction, and adaptation rather than returning to an identical pre-stroke state. Many survivors report developing new perspectives, priorities, and approaches to life that sometimes result in greater life satisfaction despite ongoing challenges.

Revolutionary approaches expanding recovery possibilities

Recent advances have transformed stroke rehabilitation, offering new hope for enhanced recovery:

Virtual reality therapy provides immersive, engaging environments that simultaneously challenge physical abilities and cognitive processing. Early research indicates potentially superior outcomes compared to conventional therapy alone, particularly for upper limb function and balance recovery.

Brain stimulation techniques including transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) show promise for enhancing neural plasticity when paired with traditional therapy approaches. These non-invasive methods may help “prime” the brain for rehabilitation exercises, potentially accelerating recovery.

Stem cell therapy, while still investigational, represents a frontier in stroke recovery. Clinical trials are exploring whether introducing stem cells into damaged brain areas might enhance healing and functional restoration beyond what natural recovery mechanisms achieve alone.

Computer-brain interfaces allow some individuals with severe motor impairments to control external devices through brain activity alone, potentially restoring communication and environmental control capabilities even when physical recovery remains limited.

The critical role of ongoing rehabilitation

Recovery extends far beyond initial hospitalization, with evidence supporting continued improvement years after stroke with proper support:

Long-term studies reveal that survivors continue showing measurable gains in function when provided with appropriate therapy, even 5-10 years post-stroke—far beyond traditional recovery windows. This research has sparked a paradigm shift away from the concept of “plateauing” toward recognition of ongoing recovery potential with the right interventions.

Home-based therapy programs incorporating technology support allow intensive practice that reinforces clinical therapy sessions. Community-based exercise programs specifically designed for stroke survivors demonstrate benefits for both physical function and social connection, addressing multiple recovery dimensions simultaneously.

Personal experiences across the recovery spectrum

While individual experiences vary dramatically, common themes emerge across recovery journeys:

Many survivors describe the emotional journey as equally challenging as the physical one, working through grief, identity adjustments, and finding new purpose. The recovery process often transforms relationships, sometimes strengthening family bonds while presenting new dynamics that require adaptation from all involved.

Survivors frequently report unexpected silver linings, including deeper appreciation for life, stronger connections with loved ones, and discovering resilience they never knew they possessed. These profound personal transformations sometimes result in survivors and families rating their quality of life highly despite ongoing challenges.

Supporting someone on the stroke recovery journey

For family members supporting stroke survivors, certain approaches prove particularly helpful:

Learning about the specific type of stroke and its effects enables more effective support tailored to individual needs. Understanding that recovery fluctuates—with good days, difficult days, and plateau periods—helps maintain perspective during challenging times.

Celebrating small victories provides crucial motivation, while balancing assistance with independence allows necessary practice of skills. Advocating for comprehensive care addressing physical, cognitive, emotional, and social needs ensures all recovery dimensions receive attention.

The evolving landscape of stroke recovery

Our understanding of stroke recovery continues advancing rapidly, offering hope for even better outcomes in the future:

Precision rehabilitation approaches tailored to specific stroke types and individual characteristics promise more targeted, effective treatments. Technological innovations make intensive therapy more accessible and engaging, potentially improving compliance and outcomes.

Early prevention efforts, especially controlling high blood pressure and other risk factors, coupled with public education about stroke symptoms, remain crucial for reducing stroke incidence and severity. Community reintegration programs addressing return to work, driving, recreation, and social participation increasingly recognize that recovery extends beyond physical function to full life participation.

While the journey varies tremendously across individuals, growing evidence confirms that meaningful recovery continues far longer than previously believed. With appropriate support, determination, and access to evolving treatments, many stroke survivors achieve levels of recovery once thought impossible—transforming our understanding of what recovery truly means after this life-changing event.