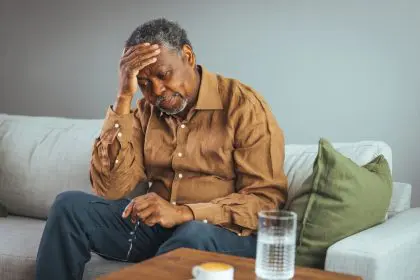

Ever notice how after demolishing that massive lunch, your brain seems to clock out for the afternoon? You’re not imagining it. That mental fog that descends after a heavy meal isn’t just food coma—it’s a legitimate cognitive decline that scientists can actually measure. And the reason behind it is both fascinating and a little alarming.

While we’ve normalized the post-meal mental slowdown as an inevitable part of eating, what’s actually happening in your brain after that burger blowout deserves more attention than the casual “food coma” label we’ve given it. The connection between your gut and your memory is more direct—and more dramatic—than most people realize.

The blood-stealing bandit in your belly

The most immediate reason your memory takes a hit after overeating comes down to a simple but critical resource allocation problem. Your body only has so much blood to go around, and after a heavy meal, your digestive system stages what amounts to a hostile takeover of your circulatory resources.

When you overindulge, your digestive system suddenly demands an enormous increase in blood flow—up to six times its normal supply. This massive diversion pulls blood away from other parts of your body, including your brain, which typically commands about 20% of your blood supply despite making up only 2% of your body weight.

With this reduced blood flow comes reduced oxygen and glucose delivery to your brain cells. Your neurons are incredibly demanding energy consumers that need constant fuel to function optimally. When that supply gets redirected to digestive duties, your cognitive functions—particularly memory formation and recall—take an immediate hit.

This blood-stealing effect helps explain why you might struggle to remember names, facts, or what you were about to say after a particularly heavy meal. Your brain is literally operating with reduced resources, almost like running a high-performance computer on low power mode.

The sugar spike memory drop

Beyond the immediate blood flow diversion, the composition of your meal—particularly its carbohydrate content—plays a crucial role in how your memory functions after eating. The relationship between blood sugar levels and cognitive function creates another pathway for post-meal memory impairment.

When you consume a carbohydrate-heavy meal, your blood glucose levels spike rapidly. Your body responds by pumping out insulin to bring those levels back down. This response often overshoots the mark, leading to a blood sugar crash. This reactive hypoglycemia hits your brain particularly hard, as glucose is its primary fuel source.

During these low blood sugar episodes, your memory processing takes a significant hit. Your hippocampus—the brain region central to memory formation—is particularly sensitive to these glucose fluctuations. When glucose availability drops, so does your ability to form new memories and recall existing ones.

This explains why carb-heavy meals tend to produce more profound memory effects than protein-rich ones. Your turkey sandwich on whole grain might cause a mild dip in mental performance, but that plate of pasta or stack of pancakes creates the perfect storm for a memory blackout.

The inflammation connection

Perhaps the most concerning link between heavy meals and memory impairment comes from the inflammatory response triggered by overeating, particularly foods high in certain fats and simple carbohydrates.

Single high-fat, high-calorie meals can trigger an immediate inflammatory response in your body. This isn’t just happening in your digestive system—it’s a system-wide reaction that includes your brain. Inflammatory markers in your bloodstream can cross the blood-brain barrier, creating neuroinflammation that directly interferes with memory processing.

This post-meal inflammation particularly affects the hippocampus, which contains a high number of receptors for inflammatory compounds. When these receptors activate, they interfere with the delicate process of memory consolidation—the transformation of short-term memories into long-term ones.

The type of food matters tremendously here. Meals high in refined carbohydrates and certain saturated fats trigger stronger inflammatory responses than those rich in omega-3 fatty acids, antioxidants, and fiber. This explains why a fast-food feast leaves you mentally foggy, while a salmon salad might actually enhance your cognitive edge.

The gut-brain communication breakdown

Your digestive system and brain maintain constant communication through what scientists call the gut-brain axis. This bidirectional highway includes the vagus nerve, immune system signaling, and the production of neurotransmitters by your gut microbiome.

Heavy meals, especially those high in sugar and low in fiber, can disrupt the balance of bacteria in your gut, leading to temporary changes in this communication system. The resulting signaling chaos can trigger changes in brain function, including memory processing.

What’s particularly interesting is that up to 90% of your serotonin—a neurotransmitter crucial for cognitive function and mood regulation—is produced in your gut. When your digestive system is overwhelmed by a heavy meal, this production can be temporarily disrupted, further contributing to the memory-impairing effects of overeating.

The connection works both ways. The stress and altered brain activity that result from digestive overload can, in turn, affect your gut function, creating a feedback loop that extends the duration of both your digestive discomfort and cognitive impairment.

The sleep quality saboteur

Another indirect way heavy meals wreck your memory comes through their impact on your sleep quality. Large meals, especially those eaten close to bedtime, significantly disrupt your sleep architecture—the natural progression through different sleep stages.

During deep sleep, your brain consolidates memories from the day, essentially transferring important information from short-term storage to long-term memory. When heavy meals interfere with this process by reducing both the quantity and quality of your deep sleep, your memory formation suffers.

Digestive discomfort, acid reflux, and the energy demands of processing a large meal can all prevent you from reaching or maintaining the deeper sleep stages where memory consolidation happens. The result is not just feeling tired the next day, but actually having impaired recall of information from the previous day.

This sleep disruption effect explains why late-night feasts can impair your memory not just immediately after eating, but well into the following day. Your brain simply never got the opportunity to properly process and store the previous day’s experiences.

Beating the post-meal brain drain

The good news is that you don’t have to accept memory impairment as an inevitable consequence of eating. Several strategies can help minimize the cognitive impact of meals while still allowing you to enjoy your food.

Portion control stands as the single most effective approach. Smaller meals require less blood diversion for digestion, create smaller blood sugar fluctuations, and trigger less inflammatory response. Consider eating more frequent, smaller meals rather than few massive ones if maintaining cognitive edge is important to you.

The composition of your meal makes a tremendous difference in its cognitive impact. Prioritizing protein and healthy fats while moderating carbohydrates—especially refined ones—helps prevent the dramatic blood sugar swings that impair memory. Adding fiber-rich foods slows digestion and helps maintain steadier glucose levels.

Timing your most cognitively demanding tasks for before meals or at least two hours after eating allows you to work with your body’s natural energy allocation patterns rather than against them. If you absolutely must perform mentally after a meal, keep it lighter than usual.

Consider including memory-protective foods in your meals. Certain compounds like flavonoids in berries, omega-3 fatty acids in fatty fish, and curcumin in turmeric have been shown to counter meal-induced inflammation and provide neuroprotective effects that might buffer against post-meal cognitive decline.

A short, gentle walk after eating can work wonders for maintaining mental clarity. Physical activity helps regulate blood sugar response and improves circulation throughout your body—including your brain—without overtaxing your digestive system.

When to be concerned about post-meal memory issues

While some degree of cognitive dip after eating is normal, certain patterns might signal underlying issues that deserve medical attention.

If you experience extreme memory impairment after meals—like forgetting conversations that just happened or getting disoriented—this goes beyond typical food coma and warrants medical evaluation. Such severe reactions could indicate blood sugar regulation problems or other metabolic issues.

Notice if your memory impairment after eating lasts more than a few hours or seems to be worsening over time. Progressive changes might indicate developing insulin resistance or other conditions that affect both digestion and brain function.

Pay attention if you experience other symptoms alongside memory problems, such as extreme fatigue, visual changes, confusion, or mood swings. This constellation of symptoms could point to reactive hypoglycemia or other conditions requiring medical management.

That post-feast mental fog isn’t just an inevitable part of enjoying a hearty meal—it’s a signal from your body about how your eating patterns are affecting your brain function. By understanding the fascinating connections between digestion and cognition, you can make informed choices about when, what, and how much to eat when your memory performance matters most.