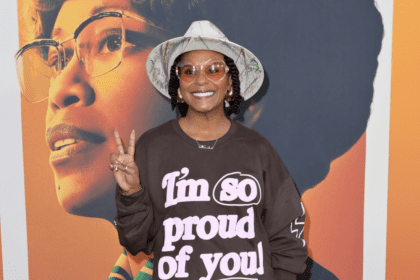

In a bookstore’s thriller section, the covers tell a familiar story: square-jawed men in tactical gear or tailored suits, occasionally interspersed with the silhouette of a femme fatale. What you won’t often find is a spy who looks like Johnny Harrington, the Black female protagonist of Judy Hutson’s debut novel “Spy Notes.” Born from Hutson’s decades of experience as a music publicist to stars like Jill Scott and Bobby Brown, Harrington represents a groundbreaking departure from espionage fiction’s well-worn tropes.

“That was very important, in fact, that was one of the other inspirations for the book,” Hutson revealed in a recent interview with Vera on “Meet the Author.” Her voice carries the enthusiasm of someone finally bringing a long-held vision to life. “I love James Bond movies, I love Ian Fleming, I love the glamour of it, the different cities that he goes to, the gadgets. And every time I watched it, I always thought, ‘Why don’t we have a Black woman as a spy that could be just as glamorous and go to those different places?'”

Redefining who gets to be a spy

The spy genre has long been defined by a particular type of protagonist. From Ian Fleming’s James Bond to Robert Ludlum’s Jason Bourne, the archetype tends to be a white man with exceptional combat skills, a government affiliation, and often a troubled past. When women appear, they’re frequently relegated to supporting roles, helping or hindering the male hero’s mission.

Hutson’s Johnny Harrington shatters this mold. Not only is she a Black woman navigating spaces historically closed to people who look like her, but she comes to espionage through an unconventional route: the music industry. As a publicist to musical artists, Harrington possesses a different kind of power than the traditional spy’s physical prowess or official credentials.

“When you’re working with entertainers, you have access to different levels of society, because high society, rich people, they all want to be around stars,” Hutson explains, drawing from her own career experience. “So I was thinking that music publicists would make great spies, because they would be able to infiltrate these places that the CIA and FBI would not be able to get into that easily.”

This fresh perspective doesn’t just diversify the spy genre demographically, it expands our collective imagination about what constitutes power and who wields it. Harrington doesn’t rely on government-issued gadgets or formal training but instead leverages her professional skills and industry connections to navigate dangerous situations.

“What a publicist has to do is a lot of times what a spy has to do,” Hutson observes. “She has to think quickly, she has to make sure that things turn out correctly.”

Drawing from overlooked history

While creating a fictional Black female spy might seem like a purely imaginative exercise, Hutson anchors her narrative in historical reality. Her primary inspiration comes from Josephine Baker, the legendary Black American performer who captivated Paris in the 1920s and ’30s before serving as an intelligence operative for the French Resistance during World War II.

“She was an iconic songstress, actress in the 1920s and thirties that just took over Paris, and she was one of the biggest African American actresses, singers at that time world renowned,” Hutson recounts with evident admiration. “During World War 2, she was working with the French resistance, and while she was on tour she would get information for the French resistance from the Germans. She would find out that information and sneak it in between her music notes.”

Baker’s contribution to the Allied war effort was so significant that France honored her with a state funeral when she died. “She is now buried in Paris,” Hutson notes. “She’s only the African American woman who is buried in the same place that some of the great French people of that time.”

By drawing attention to Baker’s little-discussed espionage work, Hutson reclaims a piece of history that challenges our understanding of who has participated in intelligence gathering. The novel “Spy Notes” thus serves not only as entertainment but as a reminder that Black women have always been present in these narratives, even when they’ve been written out of the popular historical record.

Additionally, Hutson incorporates Barbados’ complex colonial history into her plot, highlighting the island’s former status as “one of the richest countries in the world because of the sugar trade” and the transportation routes between Barbados and South Carolina that once moved both enslaved people and goods. These historical details add depth to her fictional world while educating readers about often-overlooked aspects of Caribbean history.

Challenging publishing’s gatekeepers

Hutson’s journey to publication represents another form of barrier-breaking. The publishing industry, particularly in genres like thriller and espionage, has traditionally catered to a specific demographic of both authors and readers. Breaking into this space as a Black woman writing a Black female protagonist required determination and a willingness to navigate or circumvent traditional gatekeeping mechanisms.

“What excites me the most about the future of storytelling,” Hutson reflects, “is that the gatekeepers, a lot of the gatekeepers, are gone so that you can write your story and get it out there.”

She speaks with particular passion about the challenges faced by writers from marginalized backgrounds: “Especially for people of color, especially Black women, Black men, they had gatekeepers, and they were their agents and their publishers, and what is considered a good story is so subjective, and it’s subjective to the world that you live in and the people you surround yourself with.”

These subjective judgments have historically limited which stories get told and which perspectives reach mainstream audiences. “If your experience and your world experience is not that of somebody of a whole different culture, you might not relate to that story,” Hutson explains, “but there could be thousands, millions of people who would relate to that story, but because you’re the gatekeeper in publishing, it’s never heard.”

For aspiring writers, particularly those from underrepresented backgrounds, Hutson emphasizes the importance of community. “The writing community is very generous. I’ve had a lot of help and advice from writers who’ve been writing loads of books, and they’re very successful.” She also stresses that writing is “just one part of the book” and that understanding marketing is equally crucial to success.

The future of diverse storytelling

With her second Johnny Harrington novel already in progress and plans for a cozy mystery series set in Barbados, Hutson is building on the foundation she’s established with “Spy Notes.” Her protagonist will soon be “pulled into this billionaire’s tour” with “a lot more political intrigue,” expanding the character’s world and challenges.

When asked to complete the statement “Storytelling for me is a way to,” Hutson responds without hesitation: “To create my own worlds and control my own worlds.” This sentiment captures the essence of what makes her work revolutionary. By creating Johnny Harrington, Hutson has carved out space in a genre that has historically excluded characters who look like her protagonist, demonstrating that the best stories are “the ones that are authentic to that writer, to how that writer feels, and the world that that writer wants to create.”

As readers increasingly seek out diverse perspectives and publishing continues to evolve, Judy Hutson stands at the vanguard of a new wave of thriller writers redefining what espionage fiction can be and who it can feature. Her advice to aspiring writers reflects this forward-looking stance: “Read, read as much as possible in the genre that you write, because you automatically get the rhythm and the pace by reading when then you start writing.”

For those who have long loved spy stories but never saw themselves reflected in the protagonists, Johnny Harrington offers a new kind of hero, one who brings both glamour and authenticity to a genre ready for reinvention. And for Judy Hutson, this is just the beginning of what promises to be a boundary-pushing literary career.

“I really would love to be the Black female Ian Fleming,” she says, her ambition clear. “Just writing a whole bunch of Johnny Harrington books.”