You might celebrate one birthday each year, but inside your body, different organs are marching to their own biological drums. That number on your driver’s license? It’s just a rough average that masks a fascinating reality – parts of you are aging faster than others, creating an internal mosaic of youth and maturity that defies simple chronology.

This biological asynchrony isn’t random or meaningless. It reflects how your lifestyle, genetics, and environment impact different systems uniquely. Understanding these varying timelines provides powerful insights into how you might protect your most vulnerable organs while supporting those that naturally age more gracefully. Let’s pull back the curtain on your body’s hidden aging patterns.

The brain begins its journey earlier than you think

Your brain hits its peak performance surprisingly early – somewhere between ages 22 and 27 for most cognitive functions. After this developmental summit, certain capabilities begin a gradual descent while others continue improving well into middle age and beyond.

Processing speed – how quickly you can take in and respond to information – typically slows first. That’s why video game reflexes often peak in the twenties. Meanwhile, vocabulary, emotional regulation, and pattern recognition can actually improve into your sixties and seventies, explaining why wisdom genuinely accumulates with age.

What makes brain aging particularly fascinating is its responsiveness to use. Unlike organs that deteriorate predictably with time, your brain follows the “use it or lose it” principle. Regions engaged in complex thinking develop denser neural networks that resist age-related decline, creating cognitive reserves that can mask or compensate for changes elsewhere.

This explains why two 70-year-olds can have dramatically different cognitive abilities despite identical chronological age. One might show minimal decline after decades of intellectual engagement, while another faces accelerated changes after years of cognitive monotony. Your brain’s biological age has less to do with birthdays and more to do with how you’ve challenged it throughout life.

Your skin reveals secrets about your lifestyle

As your most visible organ, skin provides a transparent record of your aging process, but its timeline varies dramatically between individuals. Genetically, skin begins showing age-related changes in your twenties as collagen production naturally declines about 1% annually after age 20. This timeline accelerates or slows dramatically based on environmental exposure.

The astonishing difference between sun-exposed and protected skin reveals how dramatically lifestyle affects aging rates. Sun-exposed areas can appear 10-15 years older than protected regions on the same person. This visible discrepancy provides perhaps the clearest evidence that chronological and biological aging operate on separate tracks.

Facial skin typically ages fastest due to its thinner structure and frequent sun exposure. Meanwhile, the skin on your buttocks often remains remarkably youthful well into advanced age – a somewhat comical reminder of how protection from environmental stressors preserves youth. This stark contrast explains why dermatologists can often guess your lifestyle habits with unsettling accuracy.

Interestingly, skin doesn’t just reveal its own aging timeline but often provides clues about internal aging as well. Certain aging patterns correlate with cardiovascular health, while others signal hormonal changes or metabolic issues, making your skin a window into broader aging processes throughout your body.

The surprising resilience of your immune system

Your immune system follows one of the body’s most complex aging patterns, with some components declining while others actually strengthen with time. The thymus – which produces T cells central to immune function – begins shrinking after puberty and continues diminishing throughout life. This helps explain increased vulnerability to novel pathogens with age.

Meanwhile, your adaptive immune system – the part that remembers past infections – grows more sophisticated throughout decades of exposure to various threats. This accumulated immunological memory explains why older adults often experience milder symptoms from common viruses their bodies have encountered before.

The most fascinating aspect of immune aging is its variability between individuals. Some 80-year-olds maintain immune responses comparable to 40-year-olds, while others show accelerated decline. Factors like chronic inflammation, stress levels, and sleep quality impact immune aging more dramatically than simple passage of time.

This variable timeline means your immune system‘s biological age might differ significantly from your chronological age, with lifestyle choices creating either accelerated aging or remarkable preservation. Few other body systems demonstrate such dramatic potential for either premature deterioration or extended youthfulness.

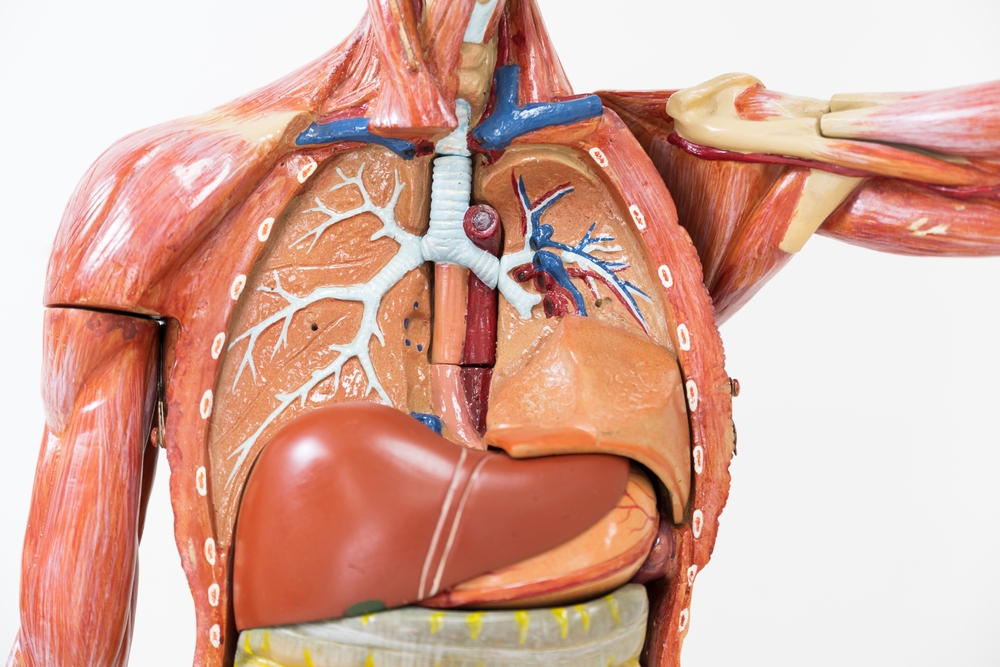

The liver’s remarkable regeneration powers

Your liver defies conventional aging wisdom through its extraordinary regenerative capacity. Unlike most organs that accumulate damage over time, the liver can replace damaged tissue throughout life, allowing it to maintain function despite decades of use.

This regenerative ability means the liver often ages more slowly than organs with less renewal capacity. A healthy 70-year-old liver typically retains about 80-90% of the function it had at age 30 – a remarkably small decline compared to many other organs over the same period.

However, this resilience has limits. Repeated damage from alcohol, certain medications, or fatty liver disease can eventually overwhelm regenerative capacity. The resulting accelerated aging creates a liver that functions like one belonging to someone decades older despite identical chronological age.

This pattern highlights a crucial principle in organ aging – baseline decline happens at a predictable rate, but lifestyle factors can dramatically accelerate or decelerate this timeline. Your liver’s biological age reflects your treatment of it far more than how many birthdays you’ve celebrated.

Your heart ages differently in men and women

Perhaps no organ demonstrates more variable aging patterns than the heart. Not only does cardiac aging differ dramatically between individuals, but significant sex-based differences create entirely different timelines for men and women.

Men typically experience earlier cardiovascular aging, with heart attack risk beginning to rise meaningfully in their mid-forties. Women generally benefit from hormonal protection until menopause, after which cardiovascular aging accelerates, eventually matching or exceeding male rates.

This sex-based difference creates about a 10-year gap in heart age between men and women of identical chronological age during middle adulthood. By older age, this gap typically narrows or reverses, with women eventually experiencing comparable or higher rates of certain heart conditions.

Beyond sex differences, individual heart aging varies dramatically based on fitness level. Regular cardiovascular exercise can essentially “freeze” heart aging, allowing some 70-year-old marathoners to maintain hearts biologically similar to sedentary 40-year-olds. Conversely, poor fitness can accelerate cardiac aging, creating the cardiovascular function of someone decades older.

The kidneys’ steady but manageable decline

Your kidneys follow one of the most predictable aging timelines of any organ. Beginning around age 30, kidney function typically declines about 0.5-1% annually, regardless of health status. This steady decrease means an 80-year-old with perfect kidney health still functions at about 50-60% of their youthful capacity.

Unlike some other organs, this decline rarely causes problems without additional risk factors. Your kidneys begin with significant functional reserves – you can lose over half your kidney function before noticeable symptoms develop. This buffer explains why healthy older adults rarely experience kidney problems despite predictable age-related changes.

However, risk factors like hypertension, diabetes, or certain medications can dramatically accelerate this timeline. Someone with poorly controlled diabetes might experience the kidney function of someone 20-30 years older, highlighting how disease processes can compress decades of natural aging into much shorter periods.

Kidney aging provides a perfect example of how natural organ decline interacts with health conditions. The predictable background aging creates vulnerability that other factors then exploit, leading to problems only when multiple aging accelerators combine.

The metabolic shift nobody warns you about

Your metabolic organs – primarily the pancreas and muscle tissue – undergo significant changes starting in your thirties that accelerate in middle age. Muscle cells become less responsive to insulin, while the pancreas gradually loses some capacity to produce this crucial hormone.

These changes help explain why maintaining the same weight becomes progressively harder with each decade. The average person loses 3-8% of muscle mass each decade after 30, creating a domino effect that reduces metabolic rate independent of activity level.

The fascinating aspect is how dramatically this timeline varies between individuals. Regular strength training can almost completely halt this process, preserving muscle mass and metabolic function decades beyond typical decline. Conversely, sedentary behavior accelerates this timeline, creating the metabolism of someone much older.

This variable pattern explains why some 70-year-olds maintain physiques similar to much younger individuals while others experience dramatic body composition changes. Your metabolic age reflects activity patterns and muscle preservation far more than chronological aging, making it one of the most modifiable aspects of the aging process.

The asynchronous aging of your organs reveals a powerful truth – your body isn’t wearing out uniformly but following multiple timelines influenced by genetics, environment, and lifestyle. This complexity offers both challenges and opportunities. While you can’t control the passage of time, understanding which of your organs age faster provides a roadmap for targeted interventions that might extend not just lifespan but healthspan – the period of life spent in good health.

The next time you celebrate a birthday, remember that inside your body, different parts are marking their own milestones on their own schedules. Your biological age is more mosaic than monolith – a complex picture painted by your choices as much as your calendar.