Walking patterns reveal more about health status than many realize. Subtle changes in stride, balance or foot placement may serve as early indicators of various medical conditions, often appearing before more recognizable symptoms develop.

These movement alterations—whether a mild shuffle, uneven pace or slight limp—can provide valuable insights into neurological, muscular and joint health, potentially enabling earlier diagnosis and treatment.

Reading the body’s signals

Movement patterns reflect the complex coordination between brain, nerves, muscles and joints. Disruptions in any of these systems can manifest in how a person walks.

Silent indicators: Changes in gait often emerge gradually and may be dismissed as minor inconveniences or normal aging. However, these subtle shifts frequently represent the body’s early warning system.

Clinical significance: Medical professionals routinely observe walking patterns during examinations because they provide objective evidence of various health conditions that might otherwise remain undetected.

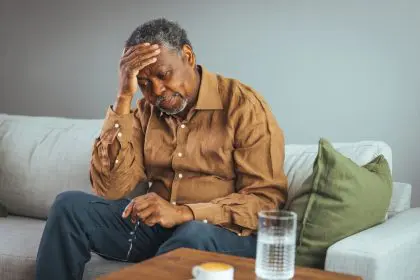

For those experiencing unexplained changes in walking ability—including slower pace, difficulty lifting feet, or increased stumbling—these symptoms warrant attention rather than dismissal.

Common gait patterns and potential causes

Specific walking abnormalities often correlate with particular health conditions:

Shuffling gait: Characterized by dragging or barely lifting feet, this pattern frequently appears in Parkinson’s disease and related movement disorders.

Waddling movement: Side-to-side swaying while walking may indicate hip dysfunction or certain forms of muscular dystrophy.

Wide-based gait: Taking unusually broad steps often signals balance problems stemming from neurological issues or inner ear disturbances.

High-stepping pattern: Exaggerated lifting of the feet, particularly common in diabetic neuropathy, typically indicates difficulty feeling the ground properly due to nerve damage.

Hesitant walking: Slow, cautious steps might reflect cognitive changes or fear of falling, particularly in older adults.

These patterns help clinicians trace symptoms to their underlying causes, whether originating in the brain, spinal cord, peripheral nerves or musculoskeletal system.

Neurological conditions

Several neurological disorders first manifest through walking abnormalities:

- Parkinson’s disease often begins with reduced arm swing, shortened steps and difficulty initiating movement

- Multiple sclerosis may present with uneven steps, poor coordination or leg dragging

- Stroke can cause asymmetrical walking patterns and foot drop

- Normal pressure hydrocephalus typically shows with magnetic gait—feet appearing stuck to the floor

These walking changes sometimes appear months or years before other classic symptoms become apparent, making gait observation a valuable diagnostic tool.

Musculoskeletal issues

Joint and muscle problems frequently alter walking mechanics:

Arthritis impact: Osteoarthritis in weight-bearing joints like knees and hips causes compensatory movement patterns as people try to minimize pain.

Muscle weakness: Age-related sarcopenia (muscle loss) or specific myopathies can reduce stability and strength, affecting walking confidence and efficiency.

Structural problems: Spinal stenosis, herniated discs or other back problems often create characteristic forward-leaning or stooped walking postures.

The body naturally adapts to pain or weakness by developing alternative movement patterns, but these compensations can create additional problems over time.

Systemic conditions

Certain widespread health conditions affect gait through their impact on nerves, circulation or overall function:

Diabetic effects: Peripheral neuropathy from long-term diabetes reduces foot sensation, creating uncertain steps and balance difficulties.

Vascular issues: Poor circulation in the legs can cause pain with walking (claudication), resulting in a halting gait with frequent stops.

Vitamin deficiencies: Severe B12 deficiency can damage nerves controlling movement, sometimes causing ataxic (uncoordinated) walking patterns.

These systemic conditions highlight how walking abnormalities often reflect whole-body health rather than isolated problems.

Cognitive connections

Mental and cognitive health significantly influence movement:

Dementia link: Changes in gait speed and pattern often precede obvious memory problems in Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias.

Emotional factors: Depression typically presents with slower walking, while anxiety may create rigid, hesitant movement patterns.

Executive function: The brain’s planning and coordination abilities directly affect walking efficiency, particularly when navigating complex environments.

This mind-body connection means walking assessment provides windows into both physical and cognitive health status.

Recognizing warning signs

Several indicators suggest when walking changes warrant medical evaluation:

- Asymmetry—favoring one side over the other

- Progressive difficulty with stairs or uneven surfaces

- Increasing frequency of stumbles or near-falls

- Comments from others about changes in walking style

- Needing to concentrate on previously automatic walking movements

These red flags, especially when developing over relatively short periods, deserve professional assessment rather than accommodation or compensation.

Diagnostic approaches

When evaluating gait abnormalities, healthcare providers employ various tools:

Observational analysis: Trained clinicians can identify subtle walking pattern abnormalities through careful observation.

Quantitative assessment: Specialized laboratories use pressure-sensitive walkways and motion capture technology to measure specific gait parameters.

Comprehensive testing: Imaging studies, nerve conduction tests and blood work help identify underlying causes when gait changes appear.

Early intervention based on these assessments often leads to better outcomes and preservation of mobility.

Understanding the significance of walking patterns empowers individuals to recognize important health signals. Rather than dismissing subtle changes as inconsequential or inevitable aspects of aging, treating them as meaningful indicators can facilitate earlier diagnosis and more effective treatment of underlying conditions.

For most people, maintaining awareness of walking quality and seeking evaluation for persistent changes represents a simple yet powerful approach to protecting long-term health and mobility.