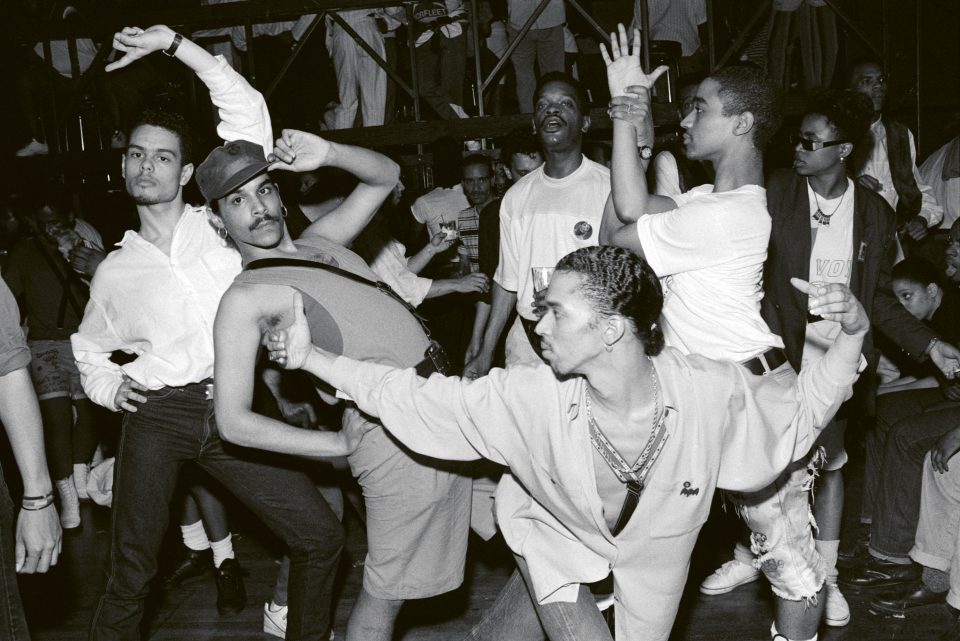

A century’s worth of significant LGBTQ+ New York City history is the focus of Marc Zinaman‘s new book, Queer Happened Here: 100 Years of NYC’s Landmark LGBTQ+ Places. With meticulous research he has compiled a documentation of popular and underrepresented spaces that have been vital to the evolution of LGBTQ+ culture and history from 1920 to 2020. Read on to hear Marc’s thoughts on the challenges behind landmarking queer spaces, the importance of redefining what is a queer space and his wish to inspire readers to appreciate history.

Only a handful of queer spaces are landmarks. What do you see as the way forward to getting more spaces landmarked?

Part of the challenge I think is that landmarking often prioritizes architectural significance or association with well-documented figures or historical events, which doesn’t always align with how queer spaces have often functioned. Many were ephemeral, constantly moving or deliberately kept under the radar because of surveillance, policing or stigma. Moving forward, I think the key would be to expand the criteria we use to define significance. It also means having the institutions in charge of landmarking engage more collaboratively with the particular communities, historians and archivists who are tirelessly working to surface the stories tied to these places, even when physical traces are gone.

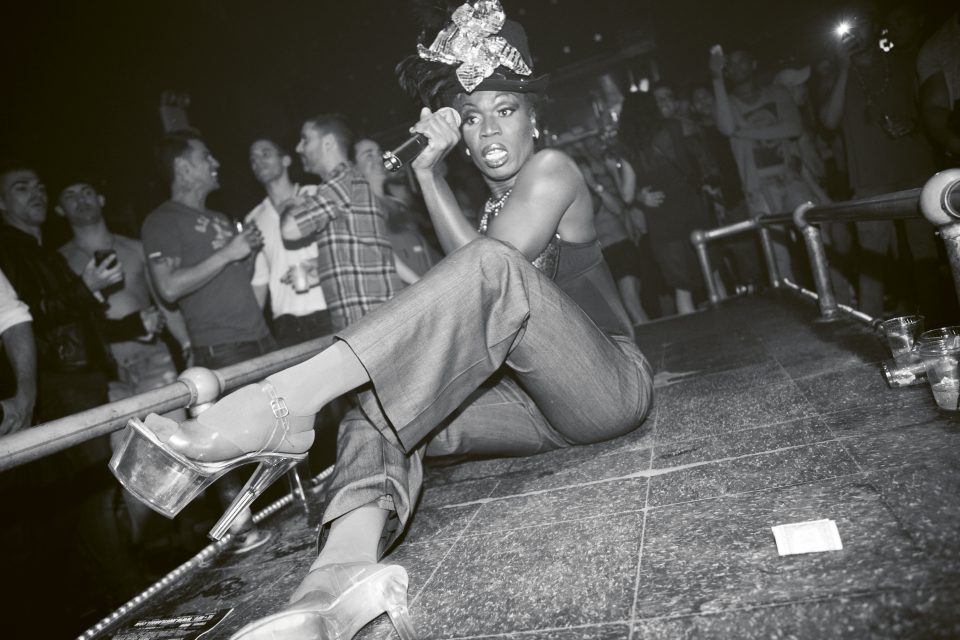

Nightclubs are heavily associated with queer spaces. But what are some of the lesser-known or surprising spaces you discovered during your research that have been central to the queer community?

In doing this research, I’m also drawn to the lesser-known or more unexpected spaces that have also played a central role in queer life, which include restaurants like Lucky Cheng’s or Stewart’s Cafeteria, bookstores like Oscar Wilde or A Different Light, and even spaces that were meant to be sites of queer oppression, like the Women’s House of Detention.

One of the most exciting parts of the Queer Happened Here project–both the book and the social media account–has been the chance to constantly expand upon the definition of what a queer space can be. So for me, as I carry on with this work an exciting goal is to continually stretch and complicate what we mean by “queer space” and recognize that they’re all worth documenting.

How do you hope readers engage with this book and its message?

I hope that readers can engage with this book and feel a sense of discovery—whether they’re encountering places they never knew existed or revisiting ones that shaped their earlier lives. And maybe some will even recognize aspects of themselves in stories from venues they never got to experience firsthand. Ultimately, I want this book to serve as both a record and a reminder: that queer people have always carved out space to connect, to celebrate and to survive. Especially now, in a political climate where LGBTQ+ rights and visibility are being challenged, it feels urgent to highlight how resilient and creative our communities have always been. In a city like New York, queer history is often hidden in plain sight, embedded in buildings and neighborhoods we pass every day. But that’s true beyond New York, too. No matter where you are, if you start looking hard enough, you’ll find traces of queer lives, spaces and stories.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.