Soy has become one of the most divisive foods in modern nutrition. As a versatile legume that forms the foundation of foods ranging from traditional tofu to modern meat alternatives, soybeans have secured their place in diets worldwide. Yet despite its popularity, soy remains surrounded by persistent questions about its effects on hormones, thyroid function, and overall health.

The nutritional profile of soy

Before addressing the controversies, it’s worth examining what makes soy nutritionally valuable. Soybeans offer an impressive array of essential nutrients:

A complete protein source containing all nine essential amino acids, rare among plant foods

Rich fiber content supporting digestive health and satiety

Heart-healthy unsaturated fats including omega-3 fatty acids

Vital minerals such as potassium, magnesium, iron and folate

Vitamin K, important for blood clotting and bone health

This nutritional density explains why soy has become a dietary staple for many people, particularly those following plant-based eating patterns. A single serving of soy foods typically provides significant portions of daily protein and mineral requirements.

Common soy foods and their differences

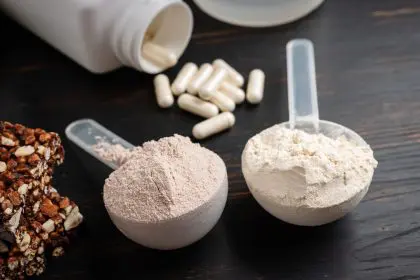

Not all soy products offer equal nutritional benefits. The processing method significantly impacts the final food’s nutritional value:

Traditional minimally processed soy foods include: Edamame (whole soybeans), Tofu (soybean curd), Tempeh (fermented soybeans) and Unsweetened soy milk

Highly processed soy products include: Many plant-based meat alternatives, Soy protein isolate in protein bars and powders, Soy-based snack foods and Sweetened soy beverages.

The distinction matters because traditional soy foods retain more of their natural nutrients and contain fewer additives than their highly processed counterparts. Fermented soy products like tempeh and miso offer additional benefits through enhanced digestibility and probiotic content.

The hormone question: does soy affect estrogen levels?

The most persistent concern about soy revolves around isoflavones, plant compounds structurally similar to estrogen that can weakly bind to estrogen receptors in the body. This has led to fears about potential hormonal disruption.

Modern research provides clarity on this issue:

Moderate soy consumption (around 25 grams daily) does not significantly impact hormone levels in either men or women

Soy isoflavones differ fundamentally from human estrogen, binding much more weakly to receptors

The body processes plant estrogens differently than it does human hormones

Clinical studies consistently show that men consuming reasonable amounts of soy do not experience feminizing effects, breast development, or significant testosterone changes

While extremely high consumption might theoretically influence hormone levels, typical dietary intake falls well below concerning thresholds. Most negative claims stem from isolated case reports or studies using concentrations far exceeding what people consume through food.

Potential benefits for muscle growth and weight management

Contrary to myths about soy being inferior to animal proteins, research indicates soy protein effectively supports muscle development:

Studies comparing soy to whey protein show comparable effects on muscle growth and strength when protein content is equivalent

The complete amino acid profile of soy makes it suitable for supporting exercise recovery and muscle synthesis

For weight management, soy foods combine protein with fiber, creating greater satiety than many other protein sources. This dual action helps control appetite and supports healthy weight maintenance.

Heart health and cholesterol benefits

Substantial evidence supports soy’s positive impact on cardiovascular health:

Regular consumption of soy isoflavones correlates with reduced risk of heart disease

Soy protein can help lower LDL (bad) cholesterol levels

The FDA has acknowledged that 25 grams of soy protein daily, as part of a diet low in saturated fat, may reduce heart disease risk

These benefits likely stem from soy’s combination of heart-healthy fats, soluble fiber, and specific plant compounds that collectively support vascular function and healthy cholesterol levels.

Cancer risk: clarifying the relationship

Early concerns that soy might increase cancer risk have been largely disproven by modern research:

Population studies indicate women with higher soy intake have approximately 12% lower breast cancer risk

For breast cancer survivors, moderate soy consumption appears safe and potentially beneficial

The protective effect may be stronger when soy consumption begins earlier in life

The relationship between soy and prostate cancer also appears favorable, with some studies suggesting protective effects for men

The key distinction appears to be whole soy foods versus isolated compounds. While concentrated isoflavone supplements warrant caution, dietary soy consumption correlates with positive or neutral cancer outcomes.

Thyroid considerations: separating fact from fear

Soy contains compounds called goitrogens that can theoretically interfere with thyroid hormone production, leading to concerns about thyroid health:

In people with normal thyroid function and adequate iodine intake, moderate soy consumption does not appear to cause thyroid problems

For those with existing thyroid conditions, particularly hypothyroidism, some caution may be warranted

Monitoring thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) levels is advisable for those with thyroid disease who consume soy regularly

Cooking reduces goitrogenic compounds in soy, minimizing potential impacts

The practical takeaway is that while soy might slightly affect thyroid hormone production, the effect is rarely clinically significant in healthy individuals or those receiving proper treatment for thyroid conditions.

Menopausal symptom relief

Some women report that soy foods help manage menopausal symptoms, particularly hot flashes:

Research shows mixed results, with some studies indicating modest benefits

Individual responses vary considerably, suggesting genetic factors may influence how women respond to soy isoflavones

Asian women who consume soy throughout life report fewer menopausal symptoms than Western women, though multiple cultural and dietary factors may contribute

For women seeking natural approaches to managing menopause symptoms, modest soy consumption represents a low-risk option worth considering, particularly when choosing traditional rather than highly processed soy foods.

Who should exercise caution with soy

While soy is safe for most people, certain groups should approach it cautiously:

Individuals with soy allergies must avoid all soy products, as reactions can be severe

Those with poorly controlled hypothyroidism might consider limiting soy intake

People taking thyroid medication should separate consumption from medication times, as soy can interfere with absorption

Those with specific hormone-sensitive conditions should consult healthcare providers about appropriate soy intake

For most others, moderate consumption of whole soy foods presents minimal risk and potential benefits.

Making informed choices about soy foods

For those interested in incorporating soy into their diet, these guidelines promote maximum benefit with minimal risk:

Choose traditional minimally processed soy foods most often

Look for organic options when possible to reduce pesticide exposure

Aim for moderate consumption, typically 1-2 servings daily

Be particularly cautious with isolated soy protein supplements and concentrated isoflavone products

Consider fermented soy foods like tempeh and miso for enhanced digestibility and nutritional benefits

Maintain dietary variety rather than relying exclusively on soy for protein

The balanced perspective on soy

When examining the totality of scientific evidence, soy emerges neither as miracle food nor health threat. Instead, it represents a nutritious protein source with specific benefits and considerations.

For most people, moderate consumption of minimally processed soy foods contributes positively to a balanced diet. The concerns that have circulated about soy largely stem from misinterpreted research or studies using amounts far exceeding typical dietary intake.

As with most nutrition topics, context matters tremendously. The form of soy consumed, individual health status, and overall dietary pattern all influence how soy affects health outcomes. By approaching soy with this nuanced understanding, consumers can make informed choices that align with their personal health goals and dietary preferences.