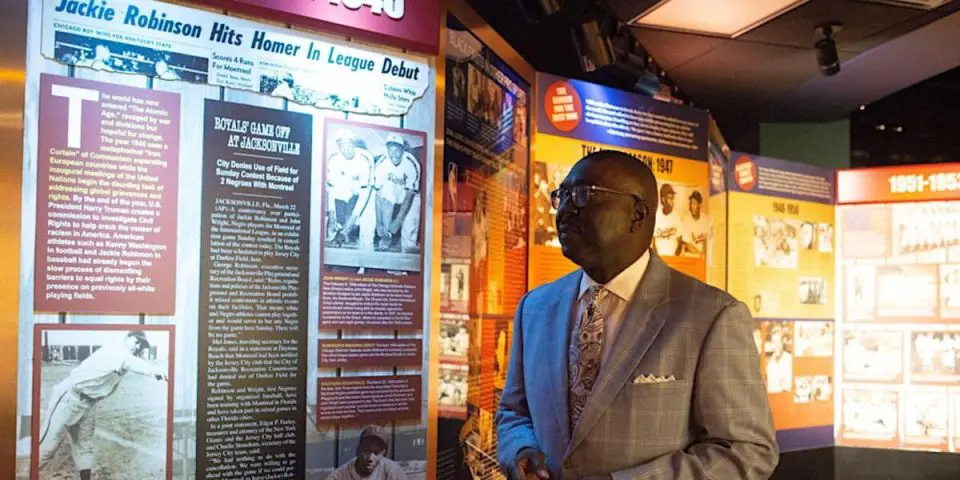

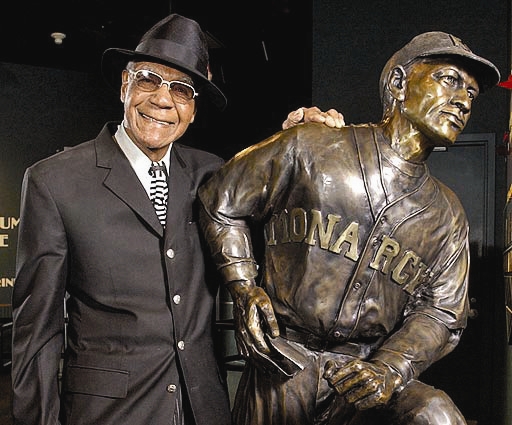

In the heart of Kansas City stands a monument to triumph, resilience, and the entrepreneurial spirit of Black America. The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum preserves not just baseball history, but a seminal chapter in American civil rights. Leading this vital institution is Bob Kendrick, whose passion for the subject radiates through every word he speaks about the legends who built their own baseball league when America’s segregation policies barred them from Major League Baseball.

In this enlightening conversation Kendrick shares why this museum matters to all Americans and highlights the incredible stories of determination that flourished despite segregation. From Satchel Paige’s legendary pitching prowess to the economic impact the Negro Leagues had on Black communities, this interview reveals why the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum represents one of America’s greatest success stories.

Why should people visit the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum?

First and foremost, it’s a forgotten piece of Americana. It had basically been ignored for decades. Really, until this museum came forward and thought it started to bring it to the forefront. What people are now discovering is that it is one of the greatest chapters, not in baseball history, but in American history. It is one of the greatest American success stories in the annals of American history. It is anchored against the ugliness of American segregation, a horrible chapter in this country’s history, but out of segregation rose this wonderful story of triumph and conquest, and, as I like to say, it is all based on one small, simple principle.

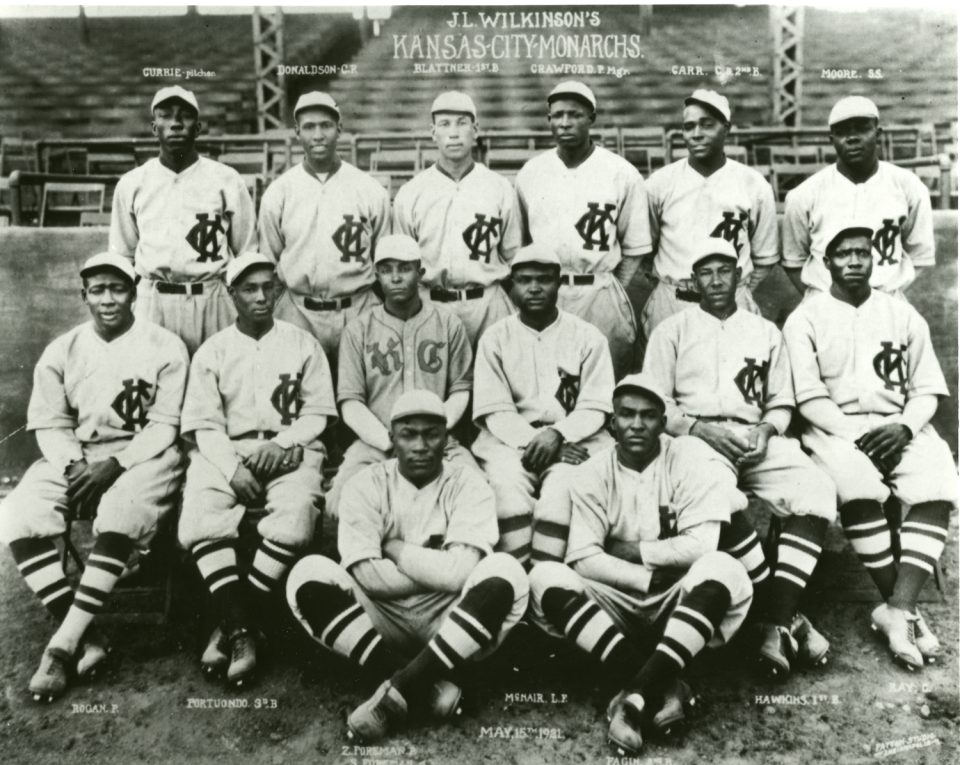

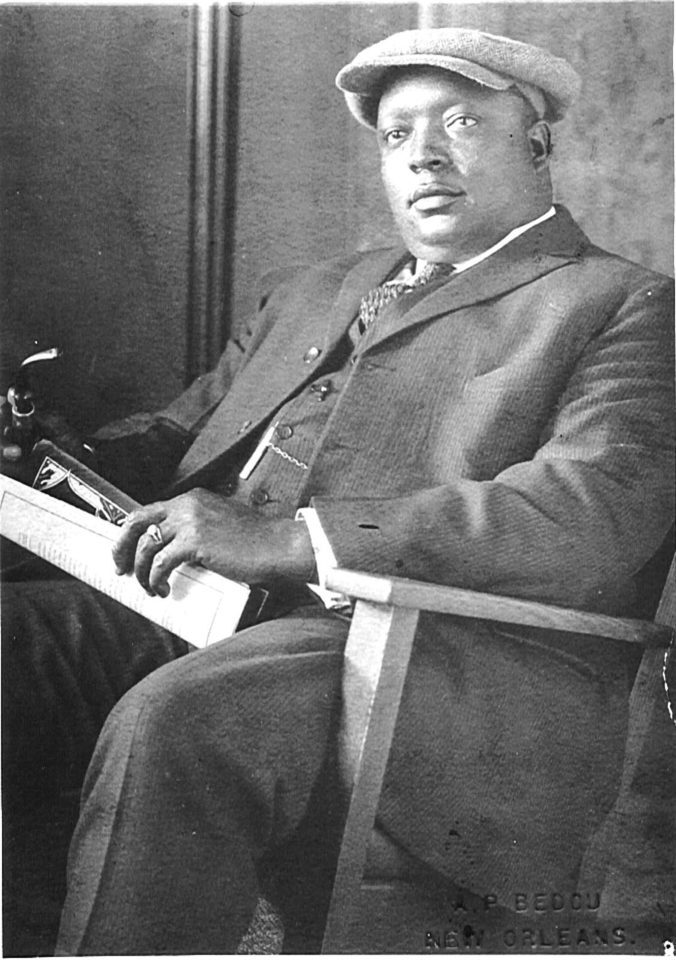

You won’t let me play with you in the Major Leagues, okay, I’ll create a league of my own. And that’s exactly what they did here in Kansas City on February 13th, 1920. A Chicagoan by the name of Andrew “Rube” Foster would lead a contingent of 8 independent black baseball team owners into Kansas City, and they formed the Negro National League. The Negro Leagues would then go on to operate for 40 years, and give us some of the greatest athletes to ever put on a baseball uniform.

What insights can you share about the depth of Satchel Paige and how he approached life?

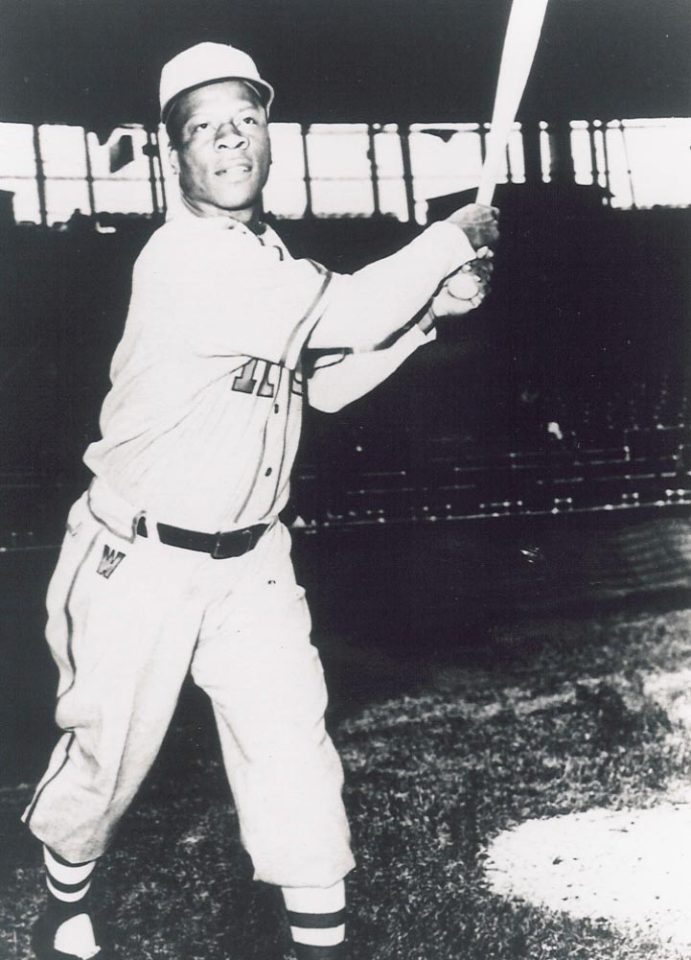

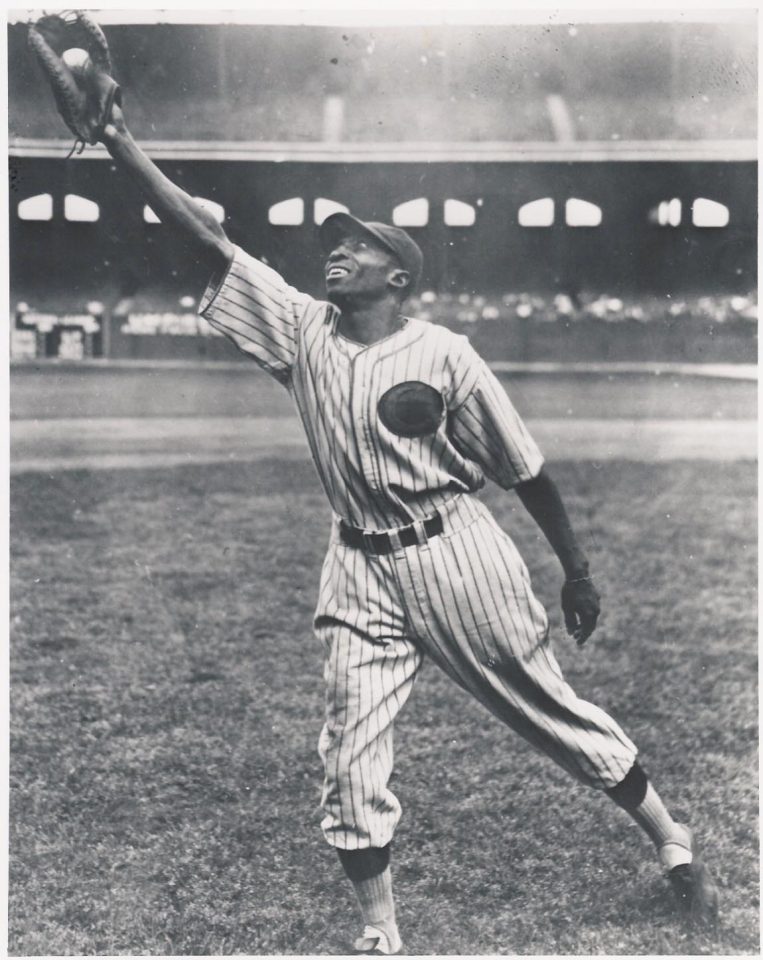

Number one, how he pulled himself out by the bootstraps literally, cause Satchel had a very troubled childhood. He was in a reform school, and he got a second chance, and he discovered baseball, and he discovered a hidden talent. When we talk about Satchel Paige, in my own opinion, we’re talking about the G.O.A.T., the greatest pitcher this sport has ever seen. We know for certain the oldest rookie in the history of Major League baseball. Major League baseball says the old man was 42 years old when he finally got his opportunity to pitch in the Major Leagues in 1948, with the Cleveland Guardians. Satchel was likely closer to 52 than 42, he never told his real age. It still remains an age-old mystery of just how old Satchel was, and he was still dominating at an ungodly age for any athlete. He was absolutely amazing.

He combined everything that you needed, in a league that was filled with big stars, he was the biggest and brightest. You combined longevity by his estimation, he pitched in over 2,600 games, recorded some 55 no hitters, and only God knows how many strikeouts and the charisma! He was the Muhammad Ali of baseball, before we ever knew who Muhammad Ali was. He could sell it, but he could back it up. He would ride into the small towns, and the entire towns would shut down to watch the old man do his thing, guaranteed to strike out the first 9, and more times than not, he did.

What can we learn from the business aspects of the Negro Leagues?

You just touched on something that is oftentimes overlooked, and I can understand why, because it’s so easy to fall in love with the romantic nature of these courageous athletes who, as I say, force a glorious history in the midst of an inglorious time in American history that we do sometimes lose sight, that the Negro Leagues was the third largest black owned business in this country. It only trailed black owned insurance companies who emerged during that era, as you know, and would insure African Americans more than the 10 to 15 cents that the white insurance companies would insure us. Essentially, the white insurance companies would insure me just enough to bury me a 10-15 cent policy. Well, black owned insurance comes about, and not only insured my livelihood but insured my stock, my crop, my home, and as a result made millions of dollars.

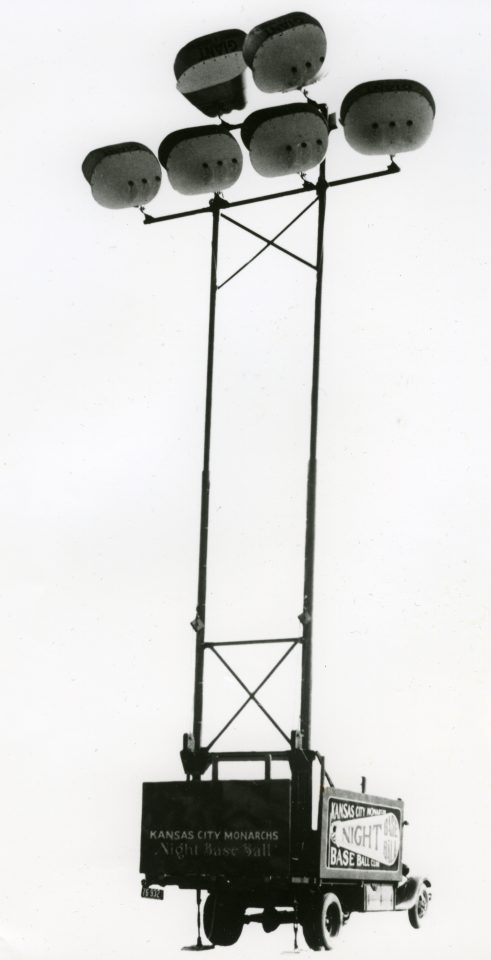

As we say, next was Madam C.J. Walker, this country’s first self-made businesswoman of any skin color, the first to earn a million dollars with a business structure, and she did it doing black hair. Next was Negro Leagues Baseball, and if my dear friend, the late great Buck O’Neil, the founder of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, legendary negro in his own right. If he was with us he’d tell you all you needed, man, was a bus, 2 sets of uniforms, and you’d have 20 of the greatest athletes who ever lived, but this was big business.

These owners were making a tremendous living. The ballplayers were making a living, playing the game that they love, and, as I tell people, and I try to describe the totality of Negro Leagues baseball, it is fascinatingly complicated, because when we lost the Negro Leagues, we lost that catalyst that sparked economic development in so many urban communities. Yeah, we gained integration, and it advanced us socially, but, it was devastating economically. Wherever you had successful black baseball, you typically had thriving black economies.

What was Louis Armstrong’s connection to the Negro Leagues?

He loved baseball, but black folks loved baseball then, everybody loved baseball, and there was no bigger fan of baseball than black folks during that era. But Louis Armstrong’s first love was baseball. He wanted to be a professional baseball player. He just happened to be a better trumpeter, and so he chose the right path. There’s a wonderful photograph that we have of Louis Armstrong and his semi-pro baseball team called the Armstrong Secret 9, and they were based out of New Orleans, as they would say.

As I tell my guests, interestingly enough, all the jazz musicians wanted to be baseball players. All the baseball players wanted to be jazz musicians, so it was only fitting that they would come together here in Kansas City, where you had the best of both worlds, jazz and baseball, radiating from that one street corner known as 18th and Vine, which in its heyday was as recognized street cross section, as there was anywhere in the world.

Why should families visit the museum and share this history with their children?

For me, and I believe this wholeheartedly, the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum is one of America’s most important civil rights, social justice institutions. It’s seen through the lens of baseball. Importantly, it’s triumph over that adversity, because most of our civil rights institutions, while they are so vitally important, they’re painful. You feel it when you go through there, there’s a weight that you carry. But see, the Negro Leagues Museum provides, what I believe to be, a counterintuitive look at the civil rights movement because this is uplifting, it is inspiring. Yeah, the stage is set against the backdrop of American segregation. A horrible chapter in this country’s history, but, as I mentioned earlier, out of segregation came this wonderful story of triumph and conquest. And so you see us in all of our glory.

It brought a tremendous sense of pride to our community, and I love when I see the entire family structure come to the Museum, because they’re passing this history down, and, as you know, there are so many gaps in the pages of American history books. And so without these cultural institutions, like the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, how are we going to learn about ourselves? We are essentially being eradicated from the pages of American history books as we speak, and so it requires an institution like the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum to bring this history to the forefront.

Where do we stand on getting Negro League records acknowledged in baseball history?

It was a seminal moment, or I dare I say, black baseball history, Negro Leagues history, American history, when May 29th of 2024, it became official that the statistics of the Negro Leagues were entered into the record books of Major League baseball and that Major League baseball had long last recognized the Negro Leagues for what I’ve always known it to be, a major league.

But this became official and it was indeed, a watershed moment, particularly for the handful of Negro League players who are still with us, their families, to see this level of atonement and recognition for what they had accomplished. And now to see the names of Josh Gibson and Oscar Charleston and Norman “Turkey” Stearnes and Boojum Wilson listed right there amongst the names of the great white major Leaguers of yesteryear.

What role did Black women play in the Negro Leagues?

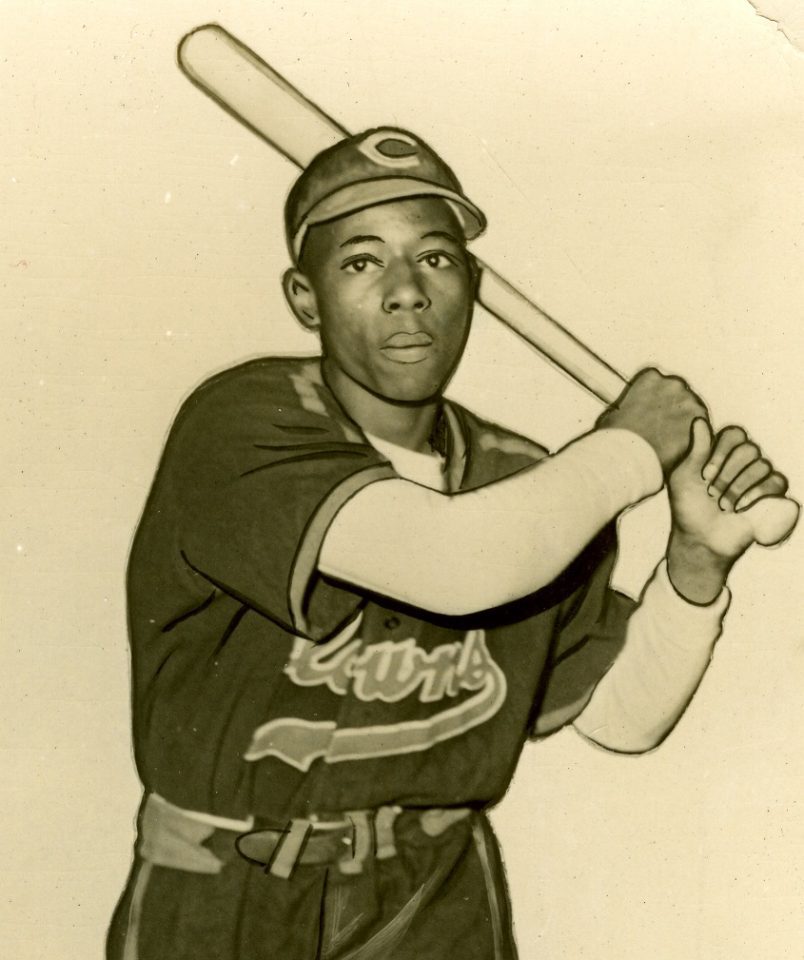

See what I love about the Negro League is that they didn’t care what color you were, and they didn’t care what gender you were. Can you play? Do you have something to offer? And as a result, 3 pioneering women call the Negro Leagues home as players, Toni Stone, Mamie “Peanut” Johnson and Connie Morgan. Women who competed with and against the men in the Negro Leagues in the 1950s. Toni Stone is the first female to play regularly in a male Professional baseball league. All 3 played for the Indianapolis Clowns in the Negro Leagues, and Toni would eventually retire from the Kansas city Monarchs.

But there were also women who were owners of Negro League teams and executives. Hilda Bolden, Olivia Taylor, Minnie Forbes, Effa Manley, Aka, the Queen of the Negro Leagues and the first woman to be nominated and inducted into the national baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. As I share oftentimes with our female guests, the Negro Leagues gave women an opportunity to do things in this country before this country gave women an opportunity to do things.