Hiding within many of our most nutritious foods is a naturally occurring compound that deserves more attention than it typically receives. Oxalic acid, also known as oxalate, exists in varying amounts in countless fruits, vegetables, nuts, and grains. While completely avoiding this compound would be nearly impossible, understanding its effects can help you make more informed dietary decisions.

Most people consume oxalic acid daily without ever realizing it. Your body even produces small amounts naturally as part of its metabolic processes. For the majority of the population, this poses no concern whatsoever. However, for specific groups, monitoring oxalate intake can make a meaningful difference in their health outcomes.

The dual nature of oxalic acid creates an interesting nutritional paradox. Many foods highest in this compound also rank among the most nutrient-dense options available. Spinach, for example, contains impressive levels of vitamins and minerals despite its high oxalate content. This complexity challenges simplistic “good food/bad food” categorizations and highlights the importance of understanding your individual needs.

The mineral-binding properties of oxalates

Oxalic acid earns its reputation as an “anti-nutrient” through its ability to bind with certain minerals in the digestive tract. When this binding occurs, both the oxalate and the mineral become less available for absorption, effectively passing through your system without delivering their nutritional benefits.

Calcium stands as the mineral most significantly affected by this binding process. When oxalic acid and calcium combine, they form calcium oxalate, which cannot be absorbed by the intestines. This interaction becomes particularly relevant for those concerned about calcium intake for bone health or those managing specific health conditions.

The binding doesn’t stop with calcium. Minerals like magnesium, iron, and zinc can also form complexes with oxalates, though to a lesser extent. For most people consuming varied diets, these interactions don’t significantly impact overall mineral status. However, those with restricted diets or increased mineral needs may benefit from being more mindful of their oxalate consumption.

Who needs to monitor oxalate intake

For most healthy individuals, oxalate consumption requires little attention. The body efficiently processes and eliminates these compounds without issue. However, specific populations benefit from greater awareness and potentially modified intake.

People with history of kidney stones stand at the top of this list. Since approximately 80% of kidney stones consist of calcium oxalate, reducing dietary oxalate can help prevent recurrence in susceptible individuals. When oxalate levels in urine become too concentrated, these compounds can crystallize and form painful stones.

Those with compromised kidney function may also need to monitor oxalate intake. Healthy kidneys efficiently filter and remove oxalates, but this process becomes impaired when kidney function declines. In such cases, oxalates can accumulate to problematic levels if dietary intake remains high.

Individuals with certain digestive conditions that affect fat absorption face increased oxalate absorption. These conditions include Crohn’s disease, celiac disease, and surgical alterations to the digestive tract. When fat digestion becomes compromised, more oxalate becomes available for absorption into the bloodstream.

Typical daily oxalate consumption

Most people consume between 50 and 200 milligrams of oxalate daily through their normal diet without any adverse effects. Some individuals may consume considerably more—up to 1,000 milligrams—especially those following plant-rich diets heavy in spinach, beets, almonds, and other high-oxalate foods.

Unlike essential nutrients, oxalic acid has no recommended daily allowance since the body doesn’t require it for any physiological functions. Instead, the focus remains on limiting excessive consumption for those at risk of complications.

For most healthy people, the body effectively regulates oxalate levels, allowing for considerable dietary flexibility. When consumed as part of a varied diet alongside adequate calcium, even moderate amounts of high-oxalate foods typically pose no health concerns.

The kidney stone connection

The relationship between oxalate and kidney stones represents the most well-established health concern associated with this compound. Kidney stones affect approximately 10% of the population at some point in their lives, with calcium oxalate stones being the most common variety.

When oxalate levels in urine rise above normal ranges (typically 20-40 milligrams per day), the risk of stone formation increases substantially. For each 100 milligrams of oxalate consumed through diet, urinary oxalate levels rise by approximately 1.7 milligrams.

This relationship between dietary intake and urinary concentration isn’t strictly linear, as several factors influence how much oxalate ultimately appears in urine. Calcium consumption, hydration status, and individual metabolism all play significant roles in determining final urinary oxalate levels.

For those who have experienced kidney stones, dietary modifications that reduce oxalate intake often form a cornerstone of prevention strategies. Combined with increased fluid intake and appropriate calcium consumption, oxalate reduction can significantly lower recurrence risk.

How oxalates affect nutrient absorption

Beyond kidney health, oxalate’s mineral-binding properties have implications for overall nutritional status. When oxalates bind to minerals in the digestive tract, both substances become largely unavailable for absorption, essentially passing through the system without imparting their benefits.

This binding activity creates an apparent nutritional contradiction. Foods like spinach contain exceptional levels of calcium on paper, yet the high oxalate content significantly reduces how much of that calcium your body can actually use. This doesn’t make spinach an unhealthy food choice, but it does highlight the importance of varied nutrition sources.

For calcium specifically, high-oxalate foods may provide as little as 5% bioavailability of their calcium content. In comparison, low-oxalate calcium sources like dairy products offer bioavailability of approximately 30-35%, making them more efficient sources of this essential mineral.

The impact on iron absorption deserves special mention, particularly for those following plant-based diets. Since plant-based iron sources (non-heme iron) already have lower bioavailability than animal-based sources, the additional reduction from oxalate binding can potentially contribute to iron deficiency if diet planning doesn’t account for this interaction.

High-oxalate foods you might eat every day

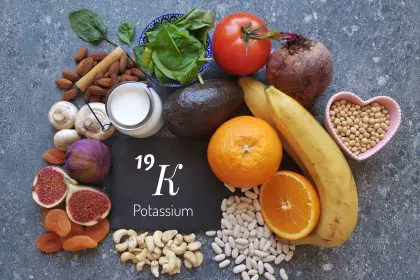

Many nutritious foods contain significant amounts of oxalate. Being aware of these sources doesn’t mean eliminating them but rather making informed choices about frequency and preparation methods.

Leafy greens vary dramatically in their oxalate content. Spinach ranks exceptionally high with approximately 750 milligrams per cup, while kale contains significantly less at about 17 milligrams per cup. Swiss chard, beet greens, and purslane also contain substantial amounts.

Root vegetables like beets, sweet potatoes, and regular potatoes contribute moderate amounts of oxalate to the diet. Their nutritional benefits often outweigh concerns about oxalate content for most people.

Nuts and seeds present another significant source, with almonds, cashews, and peanuts containing particularly high levels. A single ounce of almonds provides approximately 122 milligrams of oxalate, making them one of the most concentrated sources in common diets.

Certain fruits contain moderate oxalate levels, including raspberries, kiwi, figs, and oranges. While lower than leafy greens or nuts, regular consumption adds to daily oxalate intake.

Chocolate and tea deserve special mention as popular items with considerable oxalate content. Dark chocolate and black tea, in particular, can contribute significantly to daily oxalate consumption when consumed regularly.

Low-oxalate alternatives to maintain nutrition

For those needing to reduce oxalate intake, numerous nutritious alternatives exist that provide similar nutrients with lower oxalate content.

In the vegetable category, cruciferous options like broccoli, cauliflower, cabbage, and Brussels sprouts offer excellent nutritional profiles with minimal oxalate. These vegetables provide fiber, vitamins, and antioxidants without contributing significantly to oxalate intake.

For fruits, apples, bananas, cherries, grapes, and melons all contain relatively low oxalate levels while providing valuable nutrients. These make excellent choices for those monitoring oxalate consumption.

Protein sources like eggs, fish, poultry, and meat contain negligible oxalate levels. These foods provide complete proteins without the oxalate concerns associated with some plant proteins like soybeans or lentils.

Dairy products offer dual benefits for those concerned about oxalate. Beyond containing minimal oxalate themselves, the calcium in dairy helps bind oxalates from other foods in the digestive tract, reducing overall absorption. This makes foods like yogurt, milk, and cheese particularly valuable in diets that include some high-oxalate foods.

Cooking techniques that dramatically lower oxalate content

One of the most practical approaches to reducing oxalate intake while still enjoying nutritious foods involves modifying preparation methods. Simple cooking techniques can significantly reduce oxalate content in many foods.

Boiling stands as the most effective method for removing oxalates from vegetables. When high-oxalate vegetables are boiled, a substantial portion of their oxalate content leaches into the cooking water. For spinach, boiling can reduce oxalate content by 30-87%, depending on the cooking time and amount of water used.

Steaming, while less effective than boiling, still reduces oxalate content by approximately 5-53% in most vegetables. This method preserves more nutrients than boiling while still providing meaningful oxalate reduction.

Soaking certain foods, particularly beans and legumes, before cooking can help reduce their oxalate content. This traditional preparation method offers multiple benefits, including improved digestibility and reduced cooking time.

For maximum benefit, combine these cooking methods with discarding the cooking water, as this removes the leached oxalates rather than allowing them to reabsorb into the food. While some water-soluble vitamins will also be lost in this process, the tradeoff often proves worthwhile for those needing to restrict oxalate intake.

Smart dietary strategies for oxalate management

Beyond simply avoiding high-oxalate foods, several dietary strategies can help minimize potential issues while maintaining optimal nutrition.

Pairing high-oxalate foods with calcium-rich options represents one of the most effective approaches. When consumed together, calcium binds with oxalate in the digestive tract, preventing its absorption into the bloodstream. For example, adding milk to tea or cheese to a spinach salad reduces the amount of oxalate your body ultimately absorbs.

Maintaining proper hydration plays a crucial role in oxalate management, particularly for preventing kidney stones. Adequate fluid intake dilutes urinary oxalate concentration, reducing the likelihood of crystal formation. Aim for enough water to produce pale yellow urine throughout the day.

Spreading high-oxalate foods throughout the day rather than consuming them in a single meal helps prevent spikes in urinary oxalate levels. This approach gives your body time to process moderate amounts rather than overwhelming its capacity all at once.

Ensuring adequate calcium intake (approximately 1,000-1,200 milligrams daily for most adults) from varied sources helps manage oxalate absorption. Contrary to older beliefs, calcium restriction is counterproductive for preventing calcium oxalate kidney stones, as it actually increases oxalate absorption.

Finding balance with oxalate in your diet

For most people, the nutritional benefits of oxalate-containing foods outweigh potential concerns about their oxalate content. The key lies in balance, variety, and appropriate preparation methods.

A diverse diet naturally limits oxalate concentration from any single source while ensuring adequate intake of complementary nutrients that help offset oxalate’s effects. Rotating between different vegetables, fruits, nuts, and grains prevents overreliance on any particular high-oxalate food.

Those with specific health conditions affecting oxalate metabolism benefit from more structured approaches. Working with healthcare providers to determine appropriate oxalate limits based on individual health status, kidney function, and history provides personalized guidance beyond general recommendations.

Understanding that food quality extends beyond single compounds helps maintain perspective. Many high-oxalate foods offer exceptional nutrient density and beneficial compounds not found elsewhere. Completely avoiding these foods often creates more nutritional problems than it solves for most individuals.

When to seek personalized guidance

While general guidelines help most people navigate oxalate consumption appropriately, certain situations warrant professional guidance for personalized recommendations.

Those who have experienced kidney stones should work with healthcare providers to determine the specific type of stones they form. While calcium oxalate stones benefit from oxalate restriction, other stone types may require different dietary approaches entirely.

Individuals with compromised kidney function need specialized nutrition guidance that considers multiple aspects of their condition, including potassium, phosphorus, protein, and oxalate intake. These complex interactions require professional oversight.

People following highly restricted diets, whether for medical, ethical, or personal reasons, may need additional support to ensure nutritional adequacy while managing oxalate intake. This particularly applies to those following plant-based diets, which naturally include more oxalate-rich foods.

Anyone experiencing symptoms potentially related to oxalate consumption, such as joint pain, digestive issues, or urinary problems, should seek medical evaluation rather than self-diagnosing oxalate sensitivity, as these symptoms commonly relate to various other conditions.

Understanding oxalic acid and its implications allows for informed dietary choices without unnecessary restriction. For most people, the nutritional benefits of oxalate-containing foods far outweigh potential concerns, especially when consumed as part of a varied diet with appropriate preparation methods. By applying simple cooking techniques and balancing food choices, you can enjoy nutritious foods while minimizing any potential downsides of their oxalate content.