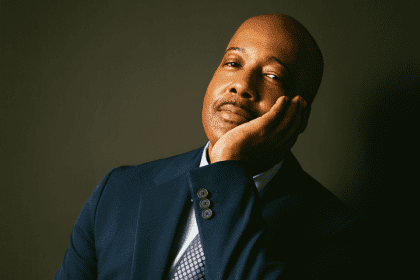

With his unmistakable warm baritone and signature newsboy cap, Gregory Porter has become one of jazz’s most compelling ambassadors. The Bakersfield-born artist, who began his journey singing in small San Diego jazz clubs while on a football scholarship, has evolved into a global phenomenon whose music transcends traditional boundaries.

From his Grammy-nominated debut “Water” to his breakthrough “Liquid Spirit” that sold over a million copies worldwide, Porter has consistently honored the jazz tradition while infusing it with his Southern gospel roots and deeply personal storytelling. His mother’s Nat King Cole record collection and the storefront church experiences of his youth created a musical foundation that would eventually carry him to sold-out performances at Carnegie Hall and Royal Albert Hall, venues his mother prophetically predicted he would conquer.

Now a two-time Grammy winner with albums like “Take Me To The Alley” and the uplifting “ALL RISE,” Porter continues to push jazz forward while carrying the torch of legends like Lou Rawls, Nat King Cole, and Abbey Lincoln. His music serves as both loving protest and spiritual uplift, addressing themes of family, identity, and the complex beauty of the Black American experience.

You work extensively, traveling 200-300 days a year. What do you want to project when you step on stage, especially knowing you’re representing a rich tradition?

Several things. There’s a lot that’s happening when I step to the stage, I am carrying a bit of my family with me. The memory of my mother is always in the music, and she’s inside of me, and quite frankly, she’s inside of other people now that they get washed with her sermons, the same sermons that washed over me. “Liquid Spirit,” “No Love Dying,” “When Love Was King”, these are all ideas, not the same wording, the ideas, the seeds were planted in me by the energy that she put into me.

Yes, I have two boys. It’s important that they get a bit of that. It’s important that they see me on stage. They travel with me, in a couple of days they’ll be with me in Poland, and so I take them all over the world with me from time to time when the school allows it.

Also, there is a thing that is happening. There’s been some lies and stories told about who black men are, and I take that message with me all over the world. I stand up in front of people, and I present myself with all of the human complexity that every other man should be allowed. I express love and anger and pride, and all of the things that exist in other people are there for me as well, and so sometimes you have to be a representative.

Your Christmas album features collaborations with artists from Detroit, including a “Purple Snowflake” tribute to Marvin Gaye. What’s your connection to Detroit?

I think my mentor Kamau Kenyatta and my producer for my first three records, he’s been there for every record as a consultant, but he’s my producer as well, and mentor. Kamau Kenyatta is from Detroit, and just the energy that he gave me, and this idea of older musicians, older men giving to younger musicians. Really, sometimes he was even showing me how to be a friend, how to be a generous musician sharing music.

So I have great respect for Detroit, and I have loved ones there, and I feel like I’m from there, but I have no claim to it properly. But in some way, all of the world has a claim to Detroit, because there’s so much soulful wisdom and hard hitting music has come out of there. Just like Harlem, it is one of the sacred grounds in terms of the production of black American culture.

“Be Good” has been described as a grown man’s lullaby. Can you explain the story behind it?

“Be Good” is a grown man’s lullaby, is what it is. I wrote the song on a bike on my way home from being essentially dismissed or dumped, and these are the words that came out. Essentially I was this big man, full of all of this masculinity, but there was this little dancer that was able to break me down and she was putting me in the cage in a way, that friend space. She took me out of the romantic and love space and put me in the friend space, and so I was caged. I was a lion in a cage, and she was quite frankly, she was afraid of where our love could go. And so this was my alliteration, finding a way to vent that love frustration and soothe myself with a grown man’s lullaby.

Oftentimes, when a man wants to express like a heart injury, it has to be done the right way. You have to still call him a lion. Don’t make him weak. You still have to give him his lion’s mane and his roar, but still express that you’ve been hurt.

How does it feel to be a global ambassador for jazz, seeing your name on signs internationally?

It’s really something, and it’s a responsibility. I do feel really fortunate to be able to carry the banner, and quite frankly, the legacy of this great music, of jazz, that speaks of a loving protest. It’s been a music that has spoken to power since the creation of the sound.

And so I lean to the understanding and the wisdom of Abbey Lincoln, Louis Armstrong, Lou Rawls, Leon Thomas. I lean to them even in my approach in terms of the themes that I want to touch on in a record or in a concert.

It goes up and down. It is love, it is protest. It is informative. It is prayer-like. It is all of the things that the diaspora of black culture can be. I think that’s important to me. I think jazz is “Fly me to the moon and let me play among the stars”, it is that. But it’s also “Precious energy flow right into me”, it’s this spirituality. It’s a little bit of church. There’s a bit of riot in it as well.

I think the modern jazz singer has a larger role in which to play. I think Nat King Cole had to consider all of the people before him. Lou Rawls had to consider all of the people before him. I have to consider Al Jarreau, Luther Vandross, and Lou Rawls and Nat King Cole and Leon Thomas. Who’s going to sing their song now that they’re gone? And we have to do that where, if not their song, their energy, who’s going to carry their energy? We have to do that. There’s a responsibility to that, and I think about it. I consider them when I step to the microphone.

When discussing women in jazz like Abbey Lincoln and Sarah Vaughan, what would you want young people to understand about their contributions?

First of all, you have to look deeper because you don’t just go to the music. There’s some subtle cues that are being given. It’s not just the music, it’s not just the dress, it’s the album covers. It’s the whole nine that’s expressing the dignity, undeniable genius.

Undeniable genius in the way that Nina Simone played the piano. She wasn’t allowed to be the great classical pianist that she wanted to be. “Oh, okay. So you’re going to keep me from doing that? Well, watch. I’m gonna put some of this classical fugue into my jazz.” And you’re going to be like, “What is that?” It’s my genius is what it is, undeniable beauty.

They were not only killing it musically, but they were killing it culturally in terms of just saying who they were as women and as black women, and as black American women.

Abbey Lincoln has a special place for me, because her songwriting was so soulful and so deep that I took cues. I take cues from her, being personal with your songwriting, writing about personal experience, understanding that the personal experience is also universal in a way that we are all the same, we all suffer the same. We all bleed red. She made these very personal songs that are quite frankly applicable to all of us.

You’ve mentioned your friendship with Stevie Wonder. If you could write a song for him, what would it be called?

My title for writing a song or record for Stevie would be “Thank You.” Thank you for the shape and the structure of the music of my life. Fortunately we have connected, and I consider him a friend now, and he has written a song for me that I have yet to collect from his house. I pinch myself when I get a birthday message from Stevie Wonder. That’s insane. I learned how to dance to his music. I was probably birthed to his music. And so it’s just extraordinary to be one of the people that’s allowed to lift up the banner of his genius. I consider myself never a peer or even a colleague, just a disciple of his mastery.

What are you still working to master in your approach to music?

I’m trying to find that middle place that is the synthesis of what you feel and what you hear, and you have to live life to feel it. To sing about your children, you might have to have children, or be an uncle. You have to hear the sad story. You have to know somebody who struggled with homelessness. You have to have empathy, and after you have that feeling, you have to bring it through that synthesis of poetry and melody. And so this is the most important thing to me is to bring my emotions, my feelings of things that move me, bringing them to melody and poetry.

Your mother clearly had profound influence on your life. Can you share what she prophesied about your career?

I’m looking at a painting of my mother now that my wife did. Considering how she moved and went about her life, how she raised us, miraculous! But all the things that she put into me that I’m now experiencing 30 years after she’s gone.

She said some things that we laughed at when we were kids, because we didn’t believe it. We didn’t have brains big enough to understand what she was putting on our foreheads. She was like, “Gregory, your gift will make room for you at the table of royalty,” and we were like, “Mom, what are you talking about?” She said, “son, you will sell out Carnegie Hall. You will sell out Royal Albert Hall.” I didn’t even know what Royal Albert Hall was. I didn’t know what Carnegie Hall was. I’ve done both of those many, many times over, and so I didn’t have room or understanding or capacity for the dreams that she had for her children. And we’re stepping right into the things that she said.

She was really extraordinary. No disrespect to other mothers, but I had a real good one.

With various musical movements happening now, from Afrobeat to country influences, how do you approach your sound evolution?

The interesting thing is for me, I’m not so calculated about it. I’m quite organic with it. If I’m feeling like I need to go back to the sound of country blues, just a twangy and whiny guitar, I’ll do that if the song calls for it or for my spirit calls for it. But I am a product of all of the things that are happening at the moment.

Afrobeat is not new, those African rhythms are not new. They’ve been ringing in our heads before we were born. If I decide to get on that it won’t be a new trend. It’ll be just me going back to what already belonged to me. The only musical steeping that I had, live musicianship that I had, was gospel music. I got out into the world and realized that gospel music is everywhere. It’s in country music. It’s in hip hop, it’s in jazz, and it’s all over R&B, soul! It’s everywhere. And so quite frankly, that gave me my passport in which to go to all of these other music.

Now, I only grew up in storefront churches. I didn’t have that 7,000 person mass choir with a bunch of matching robes. It was just me, my brother, my sister, my older brothers, and we sang these songs, that Southern gospel sound. COGIC, Church of God, Holiness Church, just enough backbeat, and those hand claps to give me enough musicality to where it reaches into all of those genres that you mentioned.