Actually, that question was posed to filmmaker Mario Van Peebles when he tried to get Posse — a movie about black cowboys and black heroism — completed back in the early 1990s.

Change the faces, change the names of the studios and change the script a little, and basically you have the same conversation some 18 years later with George Lucas. That insulting question posed to Van Peebles stuck with me because it gave me, for the first time, a peek into the inner-workings of behind-the-scenes Hollywood. I can only imagine the quizzical looks shot at Lucas and words of disdain that the floated out of studio execs’ mouths when Lucas laughably wanted to make a movie about black heroism. I say ‘laughably’ because Hollywood surely gave legend Steven Spielberg all the support to make a mostly-black movie about black pathology in The Color Purple.

I was young, black and quick-tempered and that one sentence thrown at Van Peebles — “why do you want to make a fried chicken western?” — set my mind on fire. I was engulfed with rage. I was going to support his movies, even if I had to walk the 10 miles to the theaters. I paid to see Posse and van Peeples’ next film, Panther, about 15 times apiece, going by myself, with my family members, my friends, with my then-girlfriend and by myself again. And again, and again. I was obsessed. I finally got a chance to thank Van Peebles for making Panther when I ran into him in Beverly Hills one day, because I had read books on the topics of the movies he made in the 90s — on black cowboys and the Black Panther Party. But actually watching the Huey Newton character and his Panther comrades having the fortitude to stand up against racist and criminal elements inside the police department had me spellbound.

I don’t care to guess the racial makeup of the inquisitors who asked Van Peebles that question or those who rejected Lucas. It’s axiomatic. But I will always remember the hell Van Peebles had to go through to get that movie made, and then, a worse kind of hell he had to endure in the promotion and distribution of Panther. He was crucified. They didn’t beat Van Peebles down when he made the urban classic, New Jack City, that made Wesley Snipes a box office star. But he got bludgeoned on movies that focused on black empowerment. I felt like Hollywood and the mass media were beating down a family member. I remember wanting to come to his defense in a little-brother-kind-of-way and concerned if he would maintain his sanity.

So, today, I openly wonder if the hordes of blacks who flooded the theaters in my city and caused theaters to be sold out for the George Lucas film, Red Tails, were going to the theaters because they wanted to support the film or out of defiance for Hollywood — or even because they were fearful that if Red Tails became another box-office disappointment — like the well-made Miracle at St. Ana — not another historical or biographical black film would ever be made again.

Did we go to the theaters for the right reasons? If we went to the theaters out of fear or defiance, this is a behavior that is not sustainable. I have valid fears that the next quality black movie will not get supported because no one talked bad about it or the news of its mass rejection will not seep into cyberspace. Hell, there are dozens of black films sitting on shelves of Hollywood right now, rotting with no help, no financing and no hope [click here]. Where’s the outrage? Where’s the support for those films? Reactionary, knee-jerk behavior and anger alone will not lead to positive change.

Fellow Atlanta writer Todd Williams said appropriately that “we don’t have to have a town hall meeting” to get blacks to go support films done by, and talking about, black people and the black experience. Businesswoman Nicole Harbin is extremely disgusted by the problem, even though she supported Red Tails. She knows many blacks did not know what the Tuskegee Airmen stood for or ever read about them before Red Tails. Many may not even have ever heard about them, she believes. Her Tulsa, Okla., hometown is always the subject of jokes when she tells folks where she’s from. But, Harbin says, they have no clue that, almost 100 years ago, it was the largest hub of black wealth in the world before white folks burnt it down and slaughtered hundreds of black people out of jealousy and devilish hatred.

Harbin’s and Williams’ point is this: we cannot wait until we’re insulted before we gather enough gumption and motivation to go see black films en masse. We should be exercising our enormous economic clout on the regular, not just when there’s a sense of urgency and panic. –terry shropshire

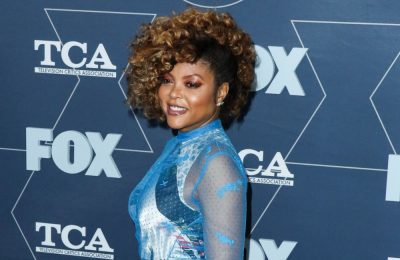

- Director and actor Mario Van Peebles, left, in “New Jack City” with Ice-T and Judd Nelson