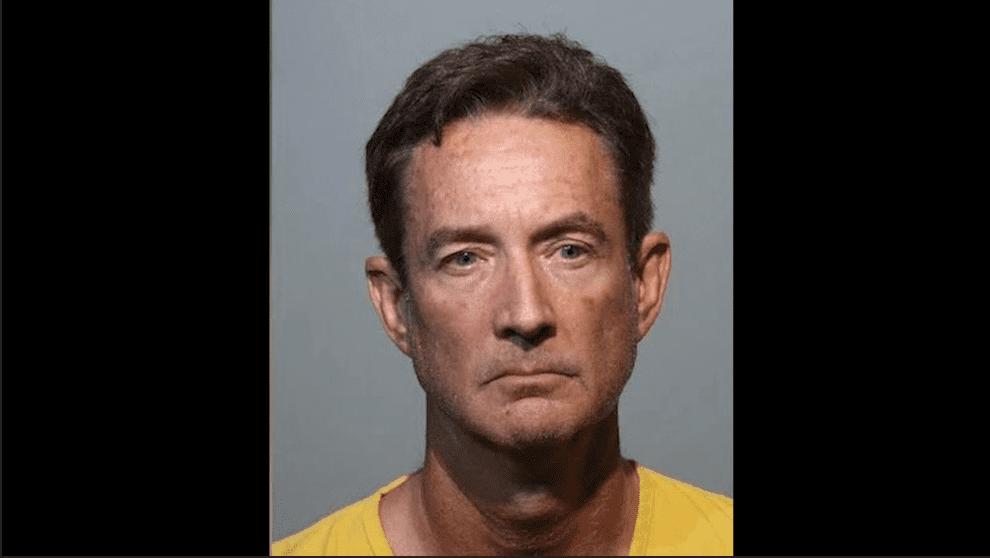

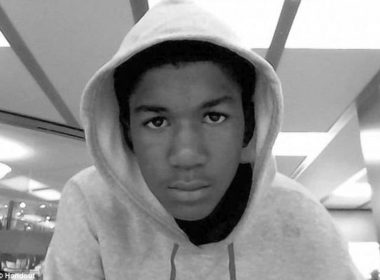

The killing of Trayvon Martin and its aftermath proved that race relations in America continues to be an ongoing problem. Civil rights leaders and upset citizens voiced their disapproval of what appears to be a case of racial profiling.

Dr. Kellie Carter Jackson, professor of African American Studies at Harvard University, teaches how the politics of violence has affected the nation since slavery.

During a recent trip to Harvard University, rolling out sat down with Dr. Jackson to discuss the Trayvon Martin case, the L.A. riots and race and violence in America. –amir shaw

The classes that you teach at Harvard focus on political and social tensions preceding the Civil War. How does the political aspect of violence then compare to what is happening today?

For me, violence is a political language and becomes a tool for oppressed people to advocate for change. It has relevancy today, because if you look at a contemporary mass movements around the world from Libya to Syria to the Occupy Wall Street movement, mass mobilized movements all revolve around a certain element of advocacy and the tool of violence always comes into question. So I ask questions such as, what makes violence inevitable? Is it inevitable? How is it useful? How can it be used as a tool? When does it succeed? When does it fail? All of those things are important for understanding how we can prevent mass calamities. The Civil War didn’t necessarily have to take place; the abolitionists were fighting for a very long time before the Civil War occur[ed]. I ask what moves a relatively nonviolent movement to a Civil War, which is one of the bloodiest, violent wars to ever take place in American history. I think if we can examine the politics that accelerate violence, perhaps it can inform other moments and movements that take place in a contemporary context. How can we prevent a particular circumstance or situation or political atmosphere from escalating to the point of violence? While the abolitionists may have succeeded in abolishing slavery, some might see the methods for their outcome as a failure.

If we consider the racial aspect of the Trayvon Martin case, things can get heated if George Zimmerman is found not guilty. How do we prevent what happened in the L.A. riots from occurring if Zimmerman is not convicted of murder?

Martin Luther King once said, “A riot is the language of the unheard.” This statement has informed my own personal ideology on many levels. In a lot of instances, mass political violence arises from rage. Rage that stems from a place where people’s voices, opinions, and desires have been unheard and unmet. When you look at chronic unemployment, massive incarceration, the break down of inner-city schools, the break down of the black family in a lot of ways, we are seeing problems that have been socially and politically engineered. For example, seeing what happened during the L.A. riots was volcanic. The idea that these four police officers could publicly and brutally beat up Rodney King and then be acquitted of all charges was absurd. But I think the reaction was so visceral, because it was an example of how disposable black people felt in their own communities. The conditions of L.A. had robbed black people of their humanity, of their dignity. When people feel as if they are disposable, it’s a very desperate place to be. I think the same thing happens with Trayvon Martin. You see a young black man walking down the street, but instead of seeing him as someone’s son, someone’s brother, he’s seen as a disposable person. Throughout history nothing has been more dismissed then the humanity and hopes of black Americans. I worry that in today’s society we no longer see people as people. We see them as pawns, we see them as products, as these almost inanimate objects that give us license to do whatever we want for the sake of maintaining the status quo. That very basic element of humanity, it sounds so cliche, but it is so crucial in listening to the language that people use. I think if you remove or impede a person’s right to a great education, the right to vote, the right to health care, the right to have a living wage, the right to a fair trial, you leave people with few little tools in their hands. I think we’ve come to a very problematic place when the only options people have in front of them is oppression or violence. Those can’t be the only two options; to be oppressed or to use violence as a way to overcome it. There has to be a way in which people can come and meet in the middle and politically decide what are the best changes to make before things escalate to something like the L.A. Riots or for the sake of my research, the Civil War. I think we spend more time extinguishing the flames of riots than we do preventing them altogether. In the 1960s, cities were all on fire for the very same reasons, but a lot of those reasons go back to how we treat people in society, how we treat people who are, in Christ’s words, “the least of these” in society. It will be indicative of how we can ever expect to go forward in the future.

What are your thoughts on individuals who believe that much of the racism that we witnessed during and before the 1960s no longer exists?

Racism has never gone away. It is alive. It is well. It is fully functioning. I think the reason why we don’t readily recognize racism is because it has evolved. Racism is so much more cloaked and complex than it was when things were very much black and white, no pun intended.