This week in Columbia, South Carolina, Deputy Ben Fields was caught on video violently slamming a 16-year-old girl to the floor in a classroom at Spring Valley High. She’d refused to leave the classroom after the teacher told her to get off her phone when Officer Fields was called in. “We already know his reputation,” 18-year-old classmate Niya Kenny told the “Today” show. “He’s known as ‘Officer Slam.’”

Since the video has gone viral, the entire country seems to have weighed in on the incident. Twitter was buzzing with Black people sharing their memories of similar incidents in their respective high schools; evidence that this is far from an anomaly in how Black youth are “disciplined.” But away from the social media hive, the conversation has confirmed that so many people still believe that brutalizing Black youth is the only way to reach them. “She shouldn’t have been on her phone” and “I was taught to respect authority” became all-too-standard responses to outrage over the video. We disregard the rebellion of White kids or simply dismiss it as “kids being kids” while Black kids are treated as soon-to-be felons in need of prison yard overseers else they run amok.

Are we so convinced that Black children are uniquely unruly and so devoted to the idea of corporal punishment that we endorse the idea that any authority figure can assault a child? This is not “back in the day” when Big Momma and Miss Jenkins would give you a whuppin’ on top of what your own momma gave you; these are authority figures with well-established biases against Black children. They aren’t coming after Black children at a disproportionate rate out of concern — this is contempt.

This past August, the Graduate School at the University of Pennsylvania released the results of an analytical study that revealed that, in 132 Southern school districts, black students were suspended at rates five times their representation in the student population, or higher. The study showed that while Black students represented just under a quarter of public school students in those states, they made up nearly half of all suspensions and expulsions. A 2014 study by the U.S. Department of Education revealed that Black children make up 18 percent of preschoolers, but make up nearly half of all out-of-school suspensions.

This is not the “good ol’ days.”

A harsh reality that those who wax nostalgic about the “good ol’ days” have to face is the fact that there are agents in our communities who are not of our communities. We have to recognize the difference — because those deemed with authority while harboring disdain will be biased in who and how they discipline; this is true whether you’re talking about classrooms or courtrooms. “It takes a village” shouldn’t be applied to those who don’t respect the village or want to be a part of it. There is no justifiable reason to believe that those authority figures should be granted the leverage to physically assault Black youth with impunity.

And as it pertains to the village, we need to ask ourselves why these incidents elicit such troubling responses from so many of us. And we need to ask why do we always “need to know more” — as CNN’s Don Lemon posited — when the victim is a Black woman.

There is an underlying “They had it coming” lurking beneath so much of the commentary and it echoes an ongoing cultural attitude that dismisses the violence that Black women —specifically — face constantly. We routinely center the “young, black male” as the focal point of Black liberation from White supremacy — as though Black womanhood isn’t under the same kind of attack.

Black women are consistently stereotyped as loud, aggressive and confrontational; and that shapes the way that we view interactions involving Black women. In the past year alone, we’ve seen video footage of a teenage Black girl being slammed to the ground at a pool party, a Black girlfriend being knocked unconscious and dragged by an NFL player and this latest incident involving the police officer at the high school in South Carolina. All of these incidents garnered national attention and mixed responses — even within the Black community.

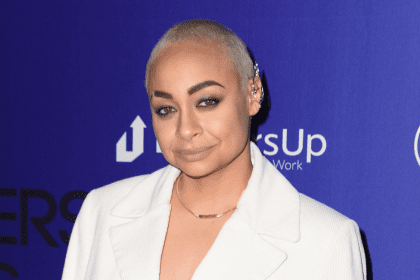

ESPN analyst Stephen A. Smith put the onus on Ray Rice’s then-girlfriend after the surveillance footage surfaced last year showing the running back punching her in an elevator. When actor Columbus Short was arrested for threatening his wife, comedian/commentator D.L. Hughley blasted her for being a “gold digger” and opportunist. “The View” co-host Raven-Symone admonished the young student in South Carolina for using her cellphone in class — as if that’s provocation enough for brute force from an officer. Popular V-103 radio personality Wanda Smith also criticized the child. The woman who was brutalized was the one being blamed for the brutality and who was subject to character dissection.

Why do we ignore, excuse and diminish assault when the victim is a Black woman? Can any of us really envision a Black male police officer hurling a teenage White girl from her desk and him being met with anything but scorn and derision? This incident at Spring Valley High is pretty clear. We shouldn’t need to “hear both sides” when a Black girl’s body is bruised by a grown man; we only need to determine how that man will be punished. He was wrong. No matter what she did — he was wrong. Regardless of where you stand on corporal punishment, regardless of how you feel about teenagers; one thing we should be able to admit is that not everyone who strikes your child does so because they love your child. And with all of the evidence and research that we’ve seen, it’s pretty easy to decide that high schools need a lot fewer “disciplinarians” like Deputy Fields.