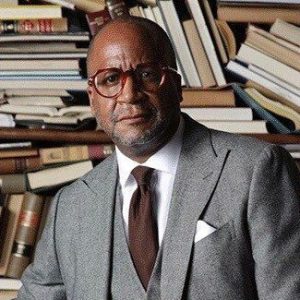

Benjamin Todd “Ben” Jealous was named the seventh executive director of the Sierra Club in November 2022.

Jealous has served in roles from organizer to investigative journalist to president of two of the nation’s most influential groups pursuing equity and justice and protecting democracy and the environment.

Jealous’s school years were spent in Pacific Grove, California, a community he describes as full of oceanographers and nature photographers. Throughout his childhood, he enjoyed summers with his grandparents in West Baltimore, Maryland, surrounded by elders who were leading civil rights activists, locally and nationally. He connected with the fights for civil rights and the environment shaped by his parents’ activism. He is the son of a white New England outdoorsman and a Black mother who had to leave Maryland when she married because interracial marriage was illegal in her native state. By 1988, Jealous split his free time between leading Youth for Jackson in his county and giving tours at the Monterey Bay Aquarium.

From 2008 to 2013, Ben led the NAACP as the youngest-ever president and CEO of the nation’s oldest and largest civil rights organization with more than 2,400 chapters. He launched the NAACP’s Climate Justice Program, which in 2012 issued Coal Blooded: Putting Profits before People, a report assessing the impact of the nation’s 378 coal-fired power plants on people of color and low-income communities. It was an extension of work Ben began in the 1990s as a reporter and managing editor at the Black-owned community newspaper, the Jackson Advocate, exposing alarming “cancer clusters” in Mississippi’s rural communities caused by industrial pollution. He also helped convince the Sierra Club and Greenpeace to join the voting rights struggle, pointing out that the forces suppressing voting were funded by the fossil fuel and paper industries that are destroying the planet.

Ben joined the Sierra Club from People for the American Way (PFAW), where he was president from 2020 through the 2022 midterm elections. At PFAW, he co-led an advocacy and civil disobedience campaign by civil rights activists, women’s rights advocates, and religious leaders to convince the Biden administration to take a more assertive role in overcoming a Senate filibuster of voting rights legislation (and was arrested numerous times in the process).

Munson Steed, the publisher and CEO of rolling out, took advantage of the opportunity to engage in a conversation with Jealous.

[Editor’s note: This is an extended transcription. Some errors may occur.]

Munson Steed: Hey, ladies and gentlemen, this is Munson Steed and welcome to another edition of CEO to CEO. I truly am amazed that the progress that we make when we have leadership around organizations. It was probably unanticipated in the past. But truly we’ve got a future that is bright. I’m here today with my dear brother, the one, the only CEO, Ben Jealous. How are you, brother?

Ben Jealous: Hey, man, it is good to be with you, Munson, and we’ve been out here on these streets for a long time, trying to do the right thing by our people. And I can remember when you launched rolling out, which now has decades of credibility under your belt. It’s just nice to see you keep on. Keep on succeeding and lifting up our people.

MS: I think that’s a very kind thing for you to say, and I truly believe and trust it, and heartfelt still the same but you’re pretty amazing yourself, brother, just to wanna stay in the fight. I mean, most people by now, given the rooms that you’ve been in, would have taken an exit. Board seat, three board seats, nice sustainability job and a huge corporation where you wouldn’t have to interface, or in any fights. What attracted you to this position as CEO, just as it relates to human rights more so than even just civil rights?

BJ: I’ve always admired people like Reverend Dr. Joseph Lowery, folks who, [late Atlanta] Mayor [Maynard] Jackson, folks just stayed in the fight their whole lives. And that’s very much what I was raised to do. I’m a fifth-generation member of the NAACP and a second-generation member of the Sierra Club, and my faith really is in these large, messy grassroots institutions. Because disproportionately, they have been responsible for our country moving in the right direction. The NAACP is that baseline throughout advancement in Black civil rights.

At any given moment it could be SNCC, it could be the Black Panther party, it could be BLM, and there’s some young group kind of capturing the zeitgeist of the moment. And yet, it’s hard to explain what got done in that decade without just the steadiness of the NAACP. The Sierra Club’s similar and they’re gonna be in different environmental groups that kind of grab all the headlines at any given moment. But see, our club is everywhere all the time. We’ve helped to create more than 400 national parks, and our Beyond Coal campaign which the NAACP was right there at the beginning, when I was leading it.

We started a climate justice program. We issued a report to help the Sierra Club in their campaign. But that campaign started, I guess about almost 20 years ago, about 15 years ago, has kept more carbon pollution out of the atmosphere than Obama’s cap and trade program would have, than the Waxman-Markey Bill, if it had passed. Whatever. But what nonprofits can say, the federal government couldn’t quite get it together. So, we stepped up and had a bigger impact. And what it gets down to is, like the NAACP, Sierra Club is a network of activists that’s in every corner of every state.

And so, that’s ultimately my faith. Both families have been here for about 400 years. My dad’s family, we know exactly when they came over to Salem, Massachusetts. It was 1624. So that’s 400 years ago this year, my mom’s family. What we know is like, we’re genetically the grandchildren of [president] Thomas Jefferson. We’re genetically the descendants of Thomas Jefferson’s grandmother, and a lot of the older families in Virginia.

Either way, I think, what those rich family histories that in this country teach you is groups like this matter. We’ve got to invest in them, as we say when we’re organizing the streets. There’s organized people. There’s organized money. Organized people can still win but we’ve got to be organized.

MS: So, for those young people that really don’t know why they should be part of the movement, or at least be in the struggle. You may not be in the streets. You might be on your phone. Why should you be a part of a struggle and part of a movement? All of your life.

BJ: Part of it is, you gotta give yourself a chance to catch up with yourself. At any given moment, Professor Hamilton, Charles Hamilton, co-author of Black Power with Stokely Carmichael said, when he taught me Politics 101 at Columbus. At any given moment, the activists tend to come from those Americans around and below university age and those Americans around and above retirement age. And so, in our middle years when we’re paying the house note, the car note, raising the kids actually is like, socially when we tend to be most conservative, just least involved and protest and activism.

And so, when my eldest child headed off to college, and my son not too far behind, I think part of this is me just kind of coming back to who I am, and really leaning back into the struggle. And for young people, I would say, now’s the time. If you don’t do it now, your 40-year-old self, your 30-year-old self, can be distracted with other things. And so lean in, and to older folks. Get back in like we need you.

And so, wherever I’ve been, NAACP or Sierra Club. I was really focused on organizing these two generations. Yes, let’s get the university kids, high school kids empowered and head in the right direction. And let’s get the retirees and the folks who don’t have kids or grandkids at home fired up and focus on the right direction. By the way, there tends to be more of the latter group. They vote more; they have more disposable income. They’re very, very powerful to organize.

MS: Yeah, when you think about environmental justice and racial equality, where should we really be thinking, what’s ahead like? What’s your vision for us moving forward?

BJ: I’m very much inspired by Frederick Douglass. Frederick Douglass really was to Dr. King what Dr. King is to most of us: the great leader from the past century who sets the North Star that we all follow. And Frederick Douglass, in [his] tirade against the Chinese Exclusion Act after the Fourteenth Amendment was passed, called our composite Nation. I’ll paraphrase and I’ll quote. To paraphrase, he says, look, every nation has a unique destiny. It seems like its mission in the world that’s based on a nation’s character. A nation’s character is that nation adds best not its worst.

And every nation’s character is ultimately shaped by its geography, and Douglass reasoned, America’s geography was unique. Reported North and South by nations. Great nations [are] defined by people with different hands, and east and west by great oceans that connect us to every person on the planet. And so Douglass reasoned, well then, our mission, defined by our character being us at our best and shape of that world connecting geography was to be, quote “the most perfect example of the unity and dignity of the human family the world has ever seen.”

And that’s fundamentally a promise as America, whenever we move closer to that, we get stronger, we’re gonna leap forward, and that’s our challenge. There’s a lot of inherent difficulties and moving beyond old patterns of xenophobia, jingoism and racism and classism, and all the things. And yet, I think as a people, the American people know, the more united we are, the more connected we are, the quicker we are to recognize the dignity of our neighbors. The better we do.

I think that the other challenge honestly in this century is really to get back to making stuff in this country. So much of the next economy, this green economy. If we’re gonna be energy independent, we gotta make the solar panels here. We gotta make the wind turbines here. We’re gonna make the batteries here. You and I went through COVID like we had a toilet paper shortage. Well, 10 years from now, about a quarter of our power is gonna come from solar. We don’t wanna end up with a solar-panel shortage.

If there’s a big storm for instance. And so I’m excited, I’m excited because I see a great opportunity to bring back manufacturing to this country and, Munson, that would solve a lot. Most Americans live in that place with 65,000 factories having shut down since NAFTA passed 30 years ago. Most Americans kind of live in some version of the same address. It’s the place where we used to have a factory and ever since it shut down, opiates have shot up, suicides have shot up, meth has shot up, misery shot up, poverty shot up.

We have the power to change that but it means we gotta get back to the old American formula that lifts all boats. We follow the science, we design the best technologies, and then we build it here, and that last part we’ve neglected at our peril for 30 years. It’s time to turn it around.

MS: So, what would you say to young entrepreneurs about participating in the green economy? I mean, you got a lot of young hustlers that just don’t know where to lean into this whole green thing. What should they be doing? What? How do they? If you’re in Chicago? What’s next? How do I get started?

BJ: It really depends. If your skills, if your inclination is more in the construction field, there’s a lot of installation jobs, and they’re gonna be there for a long time and becoming a solar installer gives a great opportunity. If you’re on the finance side, well, then, there’s a lot of money to be made financing the adoption. People will be putting these on their roofs. They’re gonna need to underwrite that. If you’re inclined to go build the factories, it is, I would say, a tougher road, and yet it’s one that if people have the inclination, and you and I have both seen in the Midwest.

Black families have managed engines, I mean manufactured engines and different components for the automobile industry, historically. They give some of the families out in Indianapolis for instance. There were suppliers to Cummings engines and things like that. Then go do it, because the reality is that everything’s heading in one direction, cars one direction, power one direction. It’s towards electrifying everything, and it’s towards renewables. And there’s a lot of money to be made there. But you gotta be aggressive, and you gotta be willing to go try something new.

MS: Something new — that’s good. You still do outreach to young people. Why get involved in environmental justice as an issue, if you’re a young person?

BJ: Fundamentally, this fight for the environment, fight for environmental justice is to fight about the future, for your family, for your kids, born or unborn. We shift the country away from coal-fired power plants. So far, we’ve shut down two-thirds in the country. That’s literally tens of thousands of heart attacks prevented, tens of thousands of lives saved, hundreds of thousands of asthma attacks prevented, disproportionately impacting our community. A lot of times when people get involved in environmental justice battles because it’s something that’s happening, it’s very local to them.

But even the broader shift away from dirty power to clean power helps clean the air in a lot of places that are overburdened with toxics in the air right now. And I think, the No. 1 reason for young people to get involved is they want to book. It is the seventh-generation responsibility that every generation has a responsibility to think seven generations out, as our native neighbors have taught us. And there’s a lot of that anxiety for a lot of young people, and they try to think that far out, while they’re watching news that every night looks like a march to the Book of Revelation.

And so, I think the reason to get involved now is really to be able to live with confidence that you’re doing everything you can for future generations on the one hand. While on the other hand, seizing all these opportunities to increase jobs in our communities, increase the health of our communities, increase wealth in our families like this big power shift. There’s a lot in that for the enterprising entrepreneur.

MS: Lastly, if you were given a speech at a Morehouse, or Fisk or Howard and you were gonna challenge the three things that you’d like to see. What would the title of your speech be for that commencement? And what would be the three things that you would want to see them do as future leaders of this country?

BJ: I would say, why we will win. It’s a speech I’m getting ready to give at a university in a couple of weeks. And in the Black Church we are taught, we claim the victory in advance, and then we go make it real. That is our people’s tradition in this country, and it has worked. We need to declare victory and that we will save planet Earth for humanity. And then, we need to go make it real. And for young people, the first thing is choosing to be optimistic. Like so many other battles in life. This one is really won by our mindset. You’ve got to just decide we can win. We will win.

Two, you then have to really prepare to lead in the next economy. There’s a bit of Booker T. Washington in that. Either you make yourself indispensable to the economy or the economy dispenses with you. Well, when the economy is headed towards all-electrics. It’s headed towards renewables. It’s about cutting-edge technologies. It’s about artificial intelligence. You’ve just gotta decide to dive into that. And then the other thing I would say to their parents, which is that, so much of what allowed us to survive, if you will, in the last half century was about, black folks getting the opportunity to go take jobs at companies like Goldman Sachs or JP Morgan or Coca-Cola.

Some big break and then you get a pension, and you get all these things. But the era that these kids are coming onto right now, it’s much more like the gap between the end of slavery and the end of segregation, when so much of what really allowed us to flourish, build wealth was entrepreneurship. And that means that parents have to be ready to say to that kid, “Yup, take the job with the startup. Yeah, I know I’ve never heard of that company before. I can’t even quite understand what it’s about. But go do that because that you get equity, that you got a shot to become one of the people who builds the next economy.”

And it wasn’t a surprise to me that the first tech billionaire of the black community was Dr. Dre. He just came from a more risk-taking culture and we fundamentally got to raise young people and give them permission to go be risk takers in moments like this. That’s how we’re going to win the future.

MS: Cool. Well, I wanna thank my dear brother, Ben Jealous. It’s always great to see you. You’ve continued to be a part of every movement that moves this country and our community forward. You do not have to be in the streets, but you must be in the struggle. I’m Munson Steed, CEO to CEO, hanging out with my brother Ben Jealous. Thank you so much, Ben.

BJ: Always good to see you, sir. Thank you for what you do.

MS: Thank you.