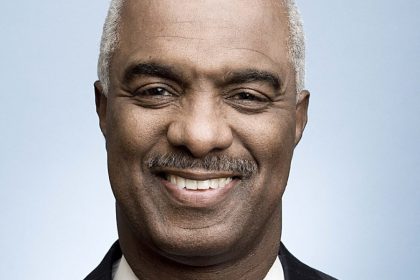

Bryant McBride is a trailblazing entrepreneur and CEO who has successfully exited seven companies. Known for his resilience and innovative spirit, McBride draws parallels between running marathons and navigating the business world.

In an exclusive interview with Munson Steed, McBride shares his journey from mastering the ice as a hockey player to revolutionizing industries as an entrepreneur and filmmaker. He offers invaluable insights on leadership, problem-solving, and the importance of continuous learning. Dive in to discover how McBride continues to transform industries and inspire with his impactful storytelling.

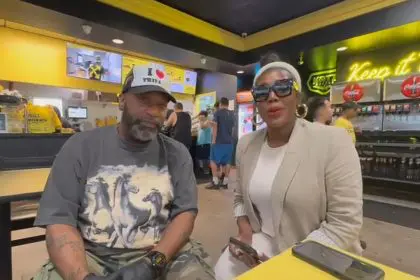

Munson Steed: Hey, everybody! This is Munson Steed, and welcome to CEO to CEO, where we introduce you to some of the most dynamic, insightful, and committed entrepreneurs and CEOs all in one. My dear brother, Bryant McBride, how are you?

Bryant McBride: I’m doing great, Munson. It’s a pleasure to be here. Thank you for having me.

MS: You’ve 7 exited it and finished marathons. What’s it like to be an entrepreneur and a CEO that has exited companies? And what should other CEOs know about the whole process?

BM: Wow! It’s a big question. There’s so much that goes into it, but I think it starts with understanding your entrepreneurial risk. Know what your DNA is, what you’ve learned, and your capacity and ability to maintain. You mentioned my good fortune to run a number of marathons. It’s really just a metaphor for entrepreneurship. This is a marathon, not a sprint. This is a survival, a will, and a desire to succeed despite incredible obstacles that appear constantly. It’s not for the faint of heart.

You have to have the entrepreneurial appetite to do it. So, I think that’s the starting point. I often analogize entrepreneurship to marathoning, except that the big difference being, in entrepreneurship, they keep moving the finish line. That’s hard, mentally, that’s really, really hard. In a marathon, you can break it into bites: you get to mile 10, then mile 17, then mile 21, and you know that you’ve got 5.2 left. You can summon the will to get there by just mental fortitude.

But in an entrepreneurial venture, they move the goal line on you after you’ve just withstood one of the hardest challenges of your life. That’s a real test. When that marathon goes from 26.2 to all of a sudden 37.8, that’s the mentality I try to bring to it. Hopefully, that’s helpful for people to think about it in that framework.

The mentality of a CEO

MS: Talk about mentality as a CEO, just from a leadership style when you approach problem-solving or the product. What should other young entrepreneurs know that as a CEO, their job is to do?

BM: Your product or service has to be 10 times better than the one that exists. If it’s not, you’re kidding yourself. That’s one thing. The other is, and I’ve seen thousands, and this is just my deduction, I could be wrong, but I’ve had it battle-tested over 25 years, and so far it’s held up: There are only three reasons that people buy companies. Everything else is BS, it’s all noise. It’s just shiny objects that get in your way and distract.

The first reason is revenue. If you’re driving revenue and a consistent trajectory upward, you’ve got a product. … You’ve got a product-market fit by then. … And customers are pulling it out of you. So, revenue is the first. The second is proprietary IP technology. If you have a product that builds something special, and people are pulling it out of you, because on the other side, on the buy side, they have a choice—they can build or buy. If you’re driving revenue and you’ve got proprietary technology, then you’re interesting.

The third piece of the puzzle, and this is related to revenue as well. All three are related to revenue frankly. The third is people — teams, badasses, the best people. John Wooden who coached with the best players win. If you have at least two of those three, if not all three, then you’ve got a good chance of exiting. If you don’t, you need to understand the chessboard. There’s usually an invisible chessboard in every vertical where companies are being bought or sold that most people just never see, don’t understand, and don’t spend the time on. But if you’re in that game, and your vertical, and driving revenue, have proprietary intellectual property, technology, and a team that is driving all of that upwards, then you’re attractive to buyers. If you’re not doing one of those three things on a daily basis as an entrepreneur, you need to reevaluate.

MS: That mentality, staying with it. When you first started thinking about hockey, another game that you know a little bit about, you’re an anomaly for most. I mean, obviously, we don’t get many invitations. It’s not an easy sport. It’s not waiting for the ball to come to you. It’s a contact sport. How is literally being a CEO a contact sport? And how do you transfer those fearless moments when you know you’re gonna get hit into your mindset? I’m just using a sports analogy, but it seems like a brother in tech, that’s a whole hockey field in itself?

BM: Absolutely, it’s a great question. And I’m gonna take it from hockey out. I tell people all the time, and as you said, I’m an anomaly. I’ve been an anomaly my whole life in that regard. Born in Chicago, but I grew up in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, Canada. They don’t let you leave unless you can play hockey, and it was one of the greatest gifts I’ve ever received: learning this sport, establishing a mastery of it, and gaining a deep knowledge of it. I make the argument all the time that the most … this is gonna sound a little crazy but stay with me.

The most important sport in the world for kids of color to play is ice hockey. People are like, “What? What are you talking about? We’re not welcome there. We don’t get many invitations.” Well, I’ve worked my whole career to change that, and I’m still working to change that. Hockey is just a metaphor for opportunity. When you step on the ice at 3, 4, 5, 7, or 10 years old, the first thing you do is fall down. The first thing you learn is to get back up. That’s a muscle you need as an entrepreneur and as a person of color in this country.

You need it over and over again. From the time you’re 5 years old, stepping onto a foreign surface like ice, everyone’s equal. White kids don’t know how to skate better than Black kids at 5 years old. Nobody knows because it’s hard. A dime’s worth of your skate is touching the surface at any one time. It’s wild to master, but once you get it, you can get it quickly, especially when you’re little. You have padding on, so falling doesn’t hurt. It’s fun. From that time in October when you’re 5 until April, you learn how to do something hard. That translates to your schoolwork, to STEM, to whatever you want. You figure out, “I can do hard things.”

That’s why the sport is so important for kids of color. You learn that an assist is the same value as a goal. It’s got all these inherent traits about teamwork, building, staying with it when you’re down 3-1 with 10 minutes left in a game. You gotta figure it out. And the way to get there, to all of that, to come from down 3-1 to tying and winning the game. And in every game you play. Hockey is a series of one-on-one battles all over the ice at hyperspeed. You’re counting on your teammates, being unselfish. It reinforces entrepreneurial, team, and leadership traits that are critical to success.

A company by a phenomenal name

MS: Thanks for that. You decide to create a new company. You’re in the space, and you think about Burst. Phenomenal name, by the way.

BM: Thank you. Expensive URL, by the way.

MS: What’s your vision? Share your vision.

BM: This is a long time ago when I started it, and that vision has shifted many times. You just have to be open to that. Every startup, this is my ninth one now. Crazy. That’s the place to start. You gotta be crazy to do this. But you also have to have this burning desire to work for yourself and not be dependent on other people who may not like you or your haircut, or whatever. I’ve been there. That’s not fun. That’s lack of control. If I’m gonna rise or fall, I want it to be on my merits. That’s why I chose entrepreneurship.

I’m basically unemployable now. But I don’t have any desire to work for anyone else. I’d rather they’re my issues, my problems, rise or fall on my strengths or weaknesses. The way I start every entrepreneurial journey is every startup is a baby. I have kids, so I’ve raised three of them successfully. Every startup is a baby. They’re learning how to walk, breathe, roll over, all those stages of childhood. That is entrepreneurship. The same care, love, and feeding. You don’t leave the baby in terms of choosing your teammates with someone you don’t trust implicitly.

Who’s going to do right by the baby, feed the baby? What kind of food are they eating? I’m going to give him a steak. He can’t handle a steak. He’s gonna get in trouble with a steak. We’re gonna run a marathon. He’s three months old. He’s gonna fall down. He can’t even do it. It doesn’t work. You really have to sequence it. Step by step, think about what the baby can handle. How do I get product-market fit? Is the baby big enough and strong enough for this? Or is my team big enough? Metaphorically, are all the pieces right to scale? Are all the pieces right? That’s the process.

In terms of the vision of Burst, I saw what social media was doing to our kids. It made me crazy. I’m in my late 50s. This was 10 years ago. I said, “Wait a second. We are putting all our most personal, private, important information inside four companies. That should work well.” Crazy. That’s what we did. So I said, “Hey, there’s gotta be niches where I can do it better, 10 times better than what Mark Zuckerberg and Jack Dorsey, now Elon Musk, what could go wrong if those guys have all our most personal information?” Crazy.

But that’s what we’ve done. The Faustian trade of “I want to know what my old girlfriend or boyfriend are doing” versus “They have 17,000 data points on me.” But we don’t think about that. That’s behind the curtain. So we said, “Media companies, stop making that Faustian bet. How about we create a product that allows you to take a video, and how about you own it rather than renting it and giving up your data, giving up your customer relationship, the ability to monetize that customer, and giving up your content?”

If you look at the fine print, Mark Zuckerberg and Elon Musk own everything on their platform. That’s crazy. There’s gotta be a way where we can do that better. And that’s what we started to do for media companies around the United States. We’ve had to pivot multiple times and find the exact fit. Very Edisonian. Have the ability and not have your ego stand in the way of, “That’s not right. I gotta fix it.” If your ego gets in the way, you can’t adjust, you can’t shift, you can’t find that revenue trajectory you need. That’s long and hard sometimes.

That’s what this one has been for us. But that ability to adapt. Edison, they once asked him, “You tried inventing the light bulb 873 different filaments. Didn’t you get frustrated?” He goes, “No, I just found 872 that didn’t work.” That’s the game.

MS: When you think about the proposition moving forward as a CEO, and many are trying to fundraise, and they’ve never had that experience, and you’ve had that, what are the keys for getting the yesses? Given that we already know you’re gonna face a no, what are those keys for just coming in and making that ask?

BM: It’s constant learning. First of all, this is embarrassing. Let me tell you something really embarrassing. I was stunned by it, frankly. Right after George Floyd, I’ve been an entrepreneur for 25 years. I’m going on my 25th year. I’ve looked at about almost 10,000 deals, all categorized in that timeframe. I’ve invested in nine. That’s it. Only things that made sense that I felt I could impact, my team could impact. Very high bar. We’re 6-1-1 on our track record so far.

We’ve invested a little over 10 and returned just over 90 prior to the venture we have in the ground right now. Lots of doubles and singles, no Google or Facebook, or NVIDIA but everyone’s eating and we’re doing okay. We’re standing, still. Which is victory in my book. We’ve created positive returns for most of our investors. Not all, but most. The first thing we look at in opportunities is, can we influence the outcome? If we can’t influence the outcome, it’s not for us. Investors on the other side are thinking the same thing. So, it’s a marriage.

The thing I’m embarrassed about is that I didn’t understand the framework until three years ago. I’m sure others watching this podcast know 2% of invested capital goes to Black entrepreneurs in this country. I did not know that until three years ago. I’m running up and down the hill for 22 years, not understanding why the hill keeps getting steeper. I felt like an idiot. You gotta understand that going in. Understand the terrain. I went to West Point. If you don’t understand the terrain and you’re in a battle, you’re gonna lose. I don’t know how I survived, frankly, looking back on it. I think it was just with a huge multicultural group of people behind me who had patience and allowed me to persevere. So, understand the terrain.

Then you’re looking for someone you’re getting married to when you take investment capital. You’re gonna spend a lot of time with that person for the next 3, 5, 7, 10 years. If they don’t see themselves hanging out with you, it’s often pattern matching. “I’m Joe White guy from Joe Suburb. Black entrepreneur! What are you about?” You just don’t have that commonality. I’m generalizing, but it’s fit. You’re looking for someone you want, and they’re looking for someone they want to hang out with, that you have the gumption to withstand all the insanity that is definitely coming.

So, that’s the way to think about it, to think. Who’s the person I want to spend in the foxhole for this amount of time, and are they going to be there when things go sideways? Because they’re looking at you the same way. The other thing that’s helpful is to understand modern portfolio theory. Modern portfolio theory is, it’s an oversimplification. But a VC takes money. Three of them are going to be awful right away. Three of them are going to be middling. 10 company portfolio. Three are going to be awful, three in the middle, and one or two have to crush it for them to keep their BMW and country club membership.

They’re looking to get rid of those seven or eight as fast as they can, so they can pour all their follow-on dollars and resources into those top two. If you’re not one of those top two, you’re done. It’s over. So I like to talk to strategics, not just pure VCs, because there are barriers there. It’s no different than policing, incarceration, schooling. There are systemic issues in this country that have persisted for hundreds of years. I don’t care what anyone says. I’ve lived it. I’m living it now. My kids live it. Just that realization of understanding the terrain is important.

Who’s going to be with you? Who can help break down the systemic barriers, and who can help you thrive when things get really hard? I’m sorry for the long-winded answer, but it’s a subject that warrants a whole hour or two to talk through in terms of fundraising. Find people that like you, that you like, that you want to run with in the hardest of times. And obviously, product market fit. Have a value proposition that shows them you can hit their benchmark. They’re looking for things that return 10 times the dollars they give you.

The filmmaker bug

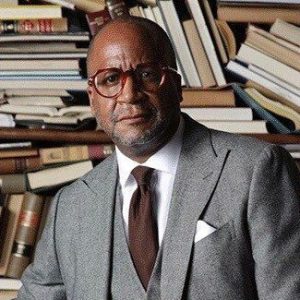

MS: Cool. Lastly, you’re a filmmaker. How’d that bug hit you? And why be a digital storyteller?

BM: Storytelling is critical. That’s what I do all day in everything I do, frame issues and opportunities and challenges as stories. People think and learn in stories. They remember stories. I’ve been a storyteller my entire life, my entire career. We all are to some degree. When I was 10 years old, I grew up in Canada, as I mentioned, Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario. I wanted to be the first Black player in the National Hockey League. No Google, dating myself. I went to the library, flipped through some books, and found Willie O’Ree, the first Black player in the NHL.

I was pretty upset with him from the time I was 10 to 12 years old. I went to good schools, worked hard, played hockey my whole teenage years, and then I was lucky enough to get in front of Gary Bettman, where I was the first Black executive at the National Hockey League. I remembered looking at that book and remembering Willie O’Ree. I wondered if he was still alive. No Google still. I looked and tried to find him, but I couldn’t. This was 1992. I called a friend, a Black FBI agent, and he’s a hockey fan. I said, “Hey, remember Willie O’Ree?” He goes, “Oh yeah.” I said, “Can you help me find him?” He goes, “Sure.” Twenty-four hours later, he came back and said, “He lives in San Diego. He’s working at the Hotel del Coronado in security.” I was like, no, that can’t be the same guy. He goes, “No, it’s him.” Full stop.

The Jackie Robinson of hockey was working security at a hotel, and everyone forgot who he was. I got on a plane, went to San Diego, and met him. I was blown away by him. Earnest, gracious, humble, incredible man. Unbelievable guy with a presence. I’ll never forget sitting in his office. Over his right shoulder, among all his memorabilia, he played for 22 years, professional hockey, was the Order of Canada, the highest civilian honor given by the Canadian Government.

That dissonance changed my life. I said, “Oh my God! This guy is an important guy, and no one knows who he is, or very few people know who he is.” I hired him, and he worked for me. He still works at the National Hockey League. He was 61 at the time. He’s 88 now. He still works at the National Hockey League today. So he’s this incredible guy. I gave him a platform, and he exploded it. On the 60th anniversary, this was five years ago, the 60th anniversary of his first game for the Boston Bruins, he invited myself, my family, his family, the Commissioner, and a whole bunch of people to celebrate Willie.

That night, it hit me, and I said to the Commissioner, “Why is he not in the Hall of Fame as a builder?” He said, “You know what? You’re right. What do you need?” I hadn’t worked at the NHL for 20 years. I said, “I’m going to need this, this, and this.” He goes, “I can’t impact that. That’s not my role as the Commissioner, but what do you need? How can I help?” That’s the night we started to get Willie into the Hockey Hall of Fame. About a third of the way through that process, I said, “We have to record this and tell the story at scale.” That’s when I became a filmmaker.

I’m not a trained filmmaker, but I have a short learning curve and figured stuff out. I just had to tell Willie’s story at scale. You can watch it on Peacock. We built a curriculum. Wayne Gretzky is in the film, Justin Trudeau is in the film. I’m an entrepreneur. We can figure stuff out. It’s the same skill set, except you need really smart people who shoot beautiful stuff. I was able to procure them and find partnerships. We made “Willie.” It’s on Peacock. It won a bunch of awards. We’re really proud of it. I’m just maniacal, and I had to make sure it grabbed people and didn’t let them go.

We make social justice films disguised as sports films. My wife calls it “We make good-tasting vegetables for America,” and we thread that needle of making sure our films teach, heal, and humanize. We did the same thing with one recently called “Beyond Their Years,” the story of Buck O’Neil and Herb Carnegie, who weren’t allowed to play at the highest levels. What they did in response to that is they changed the world. Those are the films we make.

MS: Cool. Ladies and gentlemen, I want to thank you for having my dear brother, Bryant McBride. Thank you for all that you have done to both lead and to actually give us a vision of ourselves that we wouldn’t have without your gifts. Thank you for coming on CEO to CEO.

BM: Munson, real pleasure. I am honored and humbled to spend some time with you. Thank you very much for all the work that you do.

MS: Thank you.