When RaMell Ross speaks about filmmaking, he doesn’t talk about entertainment or box office success. Instead, he describes his work as “knowledge production” – a means of engaging with the world’s complexity through a lens that challenges conventional storytelling. This perspective has served him well, from his Oscar-nominated documentary “Hale County This Morning, This Evening” to his latest triumph, the critically acclaimed and also Oscar-nominated adaptation of “The Nickel Boys.”

In my conversation with Ross, he shares his artistic vision for bringing Whitehead’s haunting narrative to the screen, which I consider quite bold. The film, which follows two boys in a Jim Crow-era reform school in Florida, showcases Ross’s distinctive approach to visual storytelling – one that demands full engagement from its audience while weaving together time travel, memory, and the duality of Black experience in America. Having read the book and now experienced the movie – because this movie is an experience so put your cell phone down while watching – I am aware of how bold storytelling can make you react on a multisensory level. I shared with the director there were several moments during the film that I was leaning in to hear, see, and interpret what was happening – and I read the book so you would think I would know the next move on screen. I didn’t and that was fine by me. Below is my conversation with this director who embraces his bold cinematic approach as a part of his DNA as an artist.

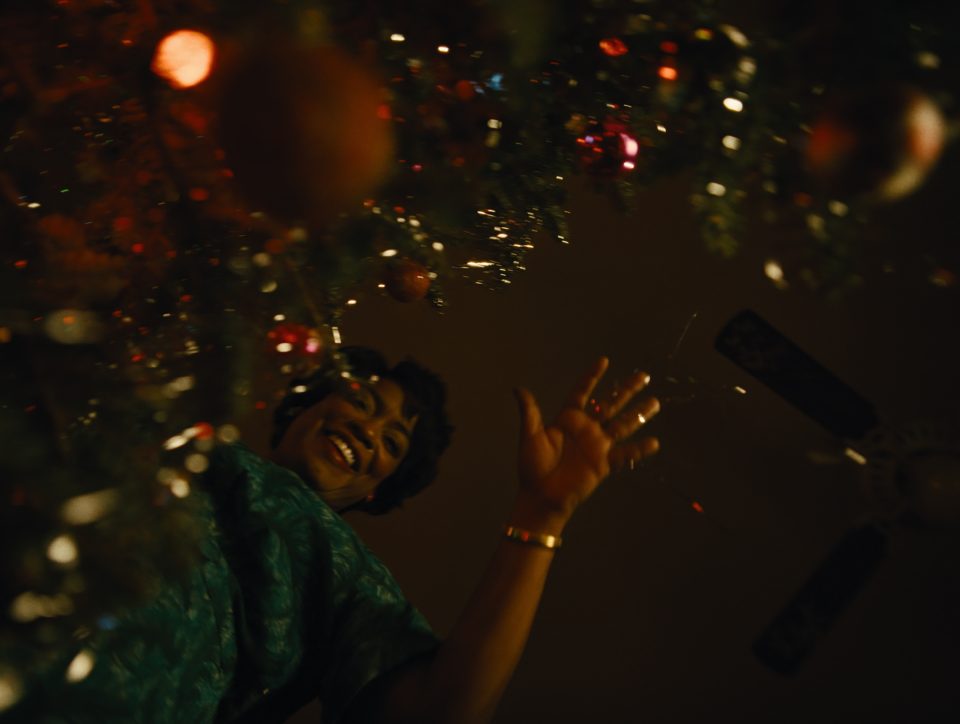

Photo credit: Courtesy of Orion Pictures © 2024 Amazon Content Services LLC. All Rights Reserved.

How are you and your community feeling about the nomination?

Thanks, Christina. I think everyone’s overjoyed. I’m overjoyed—surprised, like shocked—but also appreciative and kind of still enjoying the ride.

What drew you to this story and its adaptation?

Yeah, I think the reason why the adaptation worked so well—if one can say it worked well—is because the ideas that Colson is organizing, I think I’m just fundamentally interested in them. They’ve shaped my life and how I’ve understood the relationship between myself, my family, my community in larger society. I was fortunate enough to be asked to adapt the book and had a copy of it two months before it was released. Immediately, I started to imagine, from inside of my own experience, what it would be like to be those two boys, Elwood and Turner, who meet in the reform institution—for those who are unfamiliar with the narrative. And I think that as an on-ramp to the story, when you super identify with the characters, there’s kind of nothing better.

How did you balance your artistic approach with audience accessibility?

Yeah, I love that question because this is the challenge. I talked with Luca Guadagnino about this—he made Challengers and Call Me by Your Name, like some pretty amazing films. We both connected over trying to sneak in art-world ideas and aesthetics into commercial cinema. The balance, for me at least, is leaning on ambiguity and leaning on the poetic— leaning on what I like to call the epic banal—and having, honestly, as little narrative continuity as needed in order to have the audience just follow just enough. But then, everything else can provide a sort of reflexive and complex aesthetic experience. You know, I feel like when we’re watching films, typically, the films do the thinking for you, one could say. Aside from that, it’s also interesting to me to have an aesthetic experience of Blackness—to experience it experientially. And you know, you do that through cinema, fundamentally. But the degree to which that is true obviously varies depending on the type of approach you’re taking. So yeah, the balance is leaning on the art.

Where does your boldness come from?

Yeah, well, I think if you’re making work—I don’t make work for the audience, per se, meaning that my main goal isn’t to have them think something is good or bad, or to take them on an entertainment experience. My relationship to photography and film is knowledge production, and it’s how to engage with the world in a way that approximates the complexity of the world—not the desire to have an experience of it that makes you feel good or is just fundamentally narrative. I have nothing against that, and I love all of that work. But, you know, it’s just my practice. And I think the reason why it’s bold to audiences is because it’s not bold to me. It’s just the way that I think about making work and the way I think about making art. And that, coincidentally, is abnormal—at least in a commercial space.

How did you approach weaving different timelines together?

Yeah, that’s a really, really good question, because it’s something that has a lot to do with intuition and a lot to do with satisfying one’s own whims and desire for a type of sensory insight or visual insight. I love that you talk about time traveling because time is central to the organizing mechanism of the brain and to our consciousness. I love—there’s this quote, I forget who says this online, but he’s like, “Have you ever been to the past? Have you ever been to the future? These places don’t exist.” They exist in our heads as they relate to anxiety or memory. And to me, the process of making a narrative is most interesting when you bring in the past and the future into the present—and to do what Aristotle says: contend with the thickness of time. Like, how thick is the moment? And with that, I was fortunate to be making this in the context of Colson Whitehead’s novel, which is a phenomenal piece of literature and does the narrative work for us. We know the story, and it’s written so well that the task of Jocelyn [Barnes] and I was actually to distill, as opposed to even translate. So, I think a lot has to do with the source material that we were working with.

How did you balance the heavy themes without overwhelming the audience?

Your questions—I know they’re as much prompts as they are questions because they’re so much the process of making the film. Because you’re constantly going back and forth between—this is too much, this is too little, this is not enough, this is too much. I think, with the balance of personal narrative, narrative continuity, and aesthetics, I always lean into what’s interesting to me. I know you had to lean forward because when I thought about even making that image, I was like—wait a second. That means we’re not showing Daveed Diggs’ face. We’re shooting this entire scene from over his shoulder. This means that his entire body becomes his face. You are now reading every single element of it, looking for information, because you’re denied the one thing you normally get information from—which is the human face. And so, it’s about—I think it’s about satisfying a sort of curiosity that myself and my collaborators have had. We had an amazing director of photography, Jomo Fray, and our production designer, Nora Mendez, and co-writer Jocelyn Barnes. All of us had a curiosity. I think that when brought together—yeah, it’s ultimately the right decision. I think if anyone works in isolation, it becomes too personal, which is a strange thing because this film is—it’s like my personal poetry. It’s deeply personal, but it’s also deeply collaborative to allow the audience to really participate. And that is a tough balance.

How did you approach the duality of perspectives within Black community conversations—between survival and change?

My co-writer and I were very conscious of it, but it’s also something that’s built into Colson’s narrative. Watching his interviews, the conversation is between himself. He said—like, he is both Elwood and he is Turner. And I connected with that because I have a cynical side, and I have an optimistic side. Like, sometimes I’m skeptical, sometimes I’m Pollyannaish. Like, that’s just—I figured, like, most people are like that. And I think the power of the narrative, even before Jocelyn and I adapted it, is that Colson doesn’t make a value judgment on that. You know, as you mentioned—it’s actually people trying to survive. It’s not people not caring about the community. It’s just a response to the difficulty of being raised in a country that, one could say, wasn’t built for you. And so, I think the challenge—or I think the joy—is actually bringing those things to a sort of visceral level and allowing someone to, at times, believe that each one of those is the best route. And then, they have to be challenged within themselves to figure out maybe which one is best for them, you know?

Did you speak with survivors from the Dozier School that the story is based on?

I didn’t. I’ve talked with a couple after the fact. And, I actually just went to Dozier—to Marianna, two weeks ago. During the making? No. We definitely relied on a lot of the research that Colson had done. And there’s this amazing woman, Dr. Kimberly, who is kind of the original anthropologist who did the research for the Dozier Report. She worked at Southern Florida and produced the Dozier document. So, we were deep, deep into the facts and the unfortunate forensic tragedy of it all. But yeah, I didn’t speak with any of the survivors then.

Photo credit: Courtesy of Orion Pictures © 2024 Amazon Content Services LLC. All Rights Reserved.

How do you hope this film resonates with younger people searching for an understanding of their histories in a time where history is being muted across education systems?

It’s an interesting thing—that film fills in for history—because I think it’s both one of the most beautiful and active elements of it, but it’s also one of the most terrifying. Because film—even in the documentary space, unfortunately—is so tied to industry. It’s so tied to career. It’s so tied to, sustainability for the maker, that the decisions in it aren’t always best serving the history element of what you’re mentioning. They’re serving the connection with the audience. They’re serving the emotional. They’re serving the box office. And—not to make a huge generalization—but, it’s interesting to think about the way that these films, unfortunately, fill in spaces because of the lack of education and the lack of awareness otherwise.

How do you envision this film filling in the gaps in teaching a history younger people need to know about?

The experiential monument—which I think is interesting for those who are makers now to think about—specifically in a time in which dominant culture seems to be explicitly dead set on erasing history and rewriting it in a way that we all thought we were beyond. There’s a way to do history so that it has the same physiological impact. It’s almost like the oral storytelling you’d get from a grandparent—where you both feel it and hear it. And that’s not something that can be erased. It’s a type of memory and a type of relationship to story that—yeah, maybe—maybe transcends erasure. For lack of a better word, that’s kind of what I see Nickel Boys as—an experiential monument for the Dozier School for Boys.

What do you hope audiences take away from this film?

The films that I make—at least at this point in my life and in my interests—I believe they’re kind of a sidestep from a call to action. They’re kind of in a separate communication category than a campaign or a presentation of material for a certain type of awareness. I think I would like for the film to open up something inside someone. Like, to me, if we could live the life of another person, and live our own life, that would obviously change the entire world. People would not be as fixated on the way they think things should be—on their single experience. So, giving someone an experience—someone having an experience—is the type of knowledge that has an inarticulable consequence on their life. And so, the films are trying to be sensory. They’re trying to be so intangibly cellular that you just know something afterward. You just feel something afterward. Something is just different. And what that does for you—it can be anything from voting differently, to smiling at someone differently, to becoming an artist, to holding your spoon differently because you enjoy the taste of something. Like—I don’t know. But I think that’s where it’s interesting.