In a world of minimalism and mass production, Kim Hill stands apart as a maximalist with a mission. The designer, whose handwoven chair sculptures have earned her a place in Bloomingdale’s as their first Black furniture designer, brings ancestral traditions, vibrant colors, and authentic storytelling into every piece she creates.

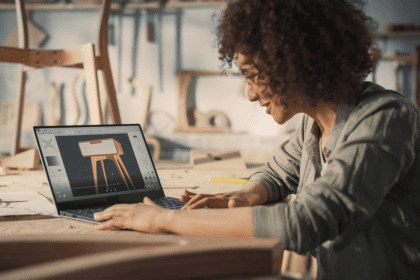

During a conversation with Munson Steed for “Design and Dialogue,” Hill reveals how a pandemic project evolved into a thriving creative practice that honors her family legacy while redefining furniture design.

Finding authenticity in design

“Design has to reflect you,” Hill explains. “It has to reflect your aesthetic and your creature comforts, your color ways. It has to resonate with you.”

This personal philosophy shapes her approach to both her own creations and her client work. When designing for others, Hill believes in drawing out their authentic selves rather than imposing her vision.

“When I’m designing something for someone else, I take Kim Hill out of the equation, at least for the first phase,” she says. “That person has to be front facing. It has to be about them.”

Her process involves asking deeply personal questions, What was your mother’s favorite color? Are you a red lipstick person or more drawn to earth tones? These inquiries help Hill uncover clients’ true design preferences, especially when they’re hesitant to express them.

“Part of why people hire designers is they’re afraid or nervous, or not confident around texture and design,” Hill notes. “They want to color outside the box, but they feel constrained.”

From pandemic necessity to artistic calling

What makes Hill’s journey particularly remarkable is how unexpectedly it began. During COVID lockdown in Newark, New Jersey, Hill was sheltering in place with her son, who was nine at the time, when inspiration struck.

“We were being advised to shelter in place, and if you did have people over, to be outside,” she recalls. “I had just moved into this house and I did not like the lawn furniture. I certainly didn’t want the same lawn furniture that everybody else was going to get.”

Looking around her home, Hill noticed the intricate weaving on the seats of antique Indonesian chairs she’d owned since her twenties. This observation coincided with memories of lawn chairs her grandmother had bought for family gatherings in upstate New York.

“Every summer we would clean out the garage, paint the floor, take down the garage door, put up screens and sit in these lawn chairs,” Hill remembers. “It was like we had this indoor-outdoor space.”

When Hill called her mother to ask about those childhood chairs, she learned they were still in storage. She collected them during a visit, brought them home, and began experimenting with removing the vinyl and creating new woven seats.

“I didn’t know what I was doing,” Hill admits. “My technique was garbage, really bad, but I knew I was onto something.”

Her intuition proved correct when a friend spotted one of her early chair experiments during a video call and immediately requested multiple pieces. Shortly after, another friend commissioned 27 chairs for a hotel in Queens. Hill had unexpectedly launched a business.

Weaving heritage into modern design

For Hill, these chair sculptures represent more than beautiful object, they’re carriers of ancestral knowledge and family heritage. Her company, Hazel and Shirley, is named after her mother Shirley and late grandmother Hazel.

“My mother, who will be 85 the same month I turn 55, didn’t get labeled the textile designer she was, but she’s a textile designer,” Hill states. “My grandmother wouldn’t have been labeled the artist that she is, but she’s also an artist.”

This sense of reclaiming and honoring undocumented creativity from previous generations permeates Hill’s work. It’s particularly meaningful that two of her grandmother’s original chair frames were featured in The New York Times.

“How serendipitous is that,” she reflects. “These weren’t expensive. These might have just been regular chairs to somebody, but my grandmother bought those, and they meant something because of the memories that were had on these chairs.”

The frames, once holding simple vinyl strapping, now showcase Hill’s intricate weaving patterns that blend influences from South American, Tunisian, Moroccan, and East African traditions.

Maximalist with a message

Hill proudly identifies as a maximalist, eschewing the minimalist trends that dominate contemporary design. Her Newark home features bold wallpaper, vibrant colors, and unexpected juxtapositions—a hairdryer in the dining room, colorful barstools, and artwork from various cultural traditions.

“Maximalists tend to have a bunch of stuff on top of a bunch of stuff. We’re not afraid to combine patterns, colors,” Hill explains. “Everything makes sense once it’s in the space.”

This embrace of abundance and layered meaning extends to her chair sculptures, which incorporate upcycled frames from American-made steel chairs sourced from a Pennsylvania junkyard.

“A big part of this early work, and still is, is upcycling—helping them stay out of a landfill,” she says. “Then reinventing them with this weaving that’s very niche and specific to my style.”

Breaking through boundaries

Becoming the first Black furniture designer carried by Bloomingdale’s represents a significant milestone for Hill and the design industry at large. “It means something,” she acknowledges. “I don’t take it lightly.”

Yet she views her work through a broader lens of storytelling and cultural preservation. “I think it comes down to these things choosing me to tell stories and continue to tell stories about how powerful we are,” Hill reflects. “Our indigenous footprint is everywhere.”

In an era she describes as a “season of erasure or attempted erasure,” Hill sees her colorful, handwoven chairs as vessels of resilience and cultural memory.

“You’re sitting in my grandmother’s prayers,” she says. “You’re going to feel it, and I think that’s a big piece that my work offers.”

Throughout the conversation, Hill returns to the theme of joy and laughter as her superpower, a deliberate choice to find and create happiness even in challenging times. Her maximalist approach to design mirrors this philosophy, embracing abundance rather than restraint.

“I’m always going to color outside the lines,” Hill declares, “and I also make the crayons.”