Designer Kim Hill doesn’t believe in boundaries or boxes, whether in her personal style, her Newark home filled with unexpected treasures, or her revolutionary approach to furniture design that earned her a historic place at Bloomingdale’s. In a candid conversation, Hill reveals how her maximalist approach to design serves as both personal expression and cultural preservation.

Embracing the “too much”

“For me, I’m Luther, it’s never too much,” Hill laughs, referencing the legendary Luther Vandross while describing her design philosophy. In her Newark home, patterns clash deliberately, colors compete for attention, and unexpected objects, like a hairdryer in the dining room, find their perfect place.

Hill proudly identifies as a maximalist in an era dominated by minimalist aesthetics. “A minimalist is like tone on tone whites and creams and grays,” she explains. “Those are the kinds of things that come together, or like ‘I like blue’ so it’s all different kinds of blues.”

Her approach stands in deliberate contrast: “Maximalists tend to have a bunch of stuff on top of a bunch of stuff. We’re not afraid to combine patterns, colors. Everything makes sense once it’s in the space.”

This philosophy extends beyond aesthetics into a way of being that embraces fullness, complexity, and authenticity.

Design as authentic storytelling

For Hill, design is inseparable from personal narrative. “I think my inspiration is always my lived experiences,” she says. “More than being an artist, I’m a storyteller.”

This storytelling approach informs not only her personal design choices but how she works with clients. Hill believes authentic design begins with understanding the person, not imposing a predetermined aesthetic.

“You really have to get to know the actual person first, or at least ask the questions so that you’re able to best amplify their beat,” she explains. “It’s so very personal.”

When working with clients, Hill delves into their personal histories and preferences: “What was your mother’s favorite color? What makes you happy when you put on a certain kind of thing? Are you a red lipstick person or more earth tone?”

She’s particularly attuned to working with clients at transitional life stages, those who’ve recently divorced, become empty nesters, or reached retirement. “Sometimes they’re in a phase where they just want to do them,” Hill notes. “They’re like, ‘I’ve waited until retirement to explore wallpaper or a cool lamp, but my husband or wife was hesitant.'”

In these moments, design becomes “very cathartic for people,” offering permission to express long-suppressed aspects of themselves.

Rejecting the boxes of black femininity

Hill’s maximalist approach extends beyond design into a life philosophy that rejects artificial limitations, particularly those imposed on Black women.

“I’ve always known that the box of Black femininity is a box that was not created by Black women,” she states, “and I’ve lived a life of constantly being asked to cram into this box.”

She observes that these limitations appear in countless contexts, “A lot of us have, no matter what you are. You’re a Black man. You’re an Asian woman. You’re tall. You got crooked teeth. You’re always reminded when you meet people at their level of discomfort.”

Hill resists these constraints, questioning why she should aspire to conventional markers of success, “It’s like the old saying of ‘a seat at the table.’ Maybe I’m not even supposed to be at a table. What makes your table so fly? Why am I supposed to be over there?”

Her rejection of societal constraints manifests in everything from her furniture designs to her lifestyle choices, including raising chickens in Newark, which surprises many people but feels perfectly natural to her.

Laughter as resistance and superpower

Throughout the conversation, Hill returns to joy and laughter as her defining characteristics and greatest strengths.

“My real superpower, I think, is my ability to laugh,” she reflects. “Through it all, I have this ability to help people laugh.”

This laughter serves multiple purposes, as genuine expression, as connection to others, and as resistance against expectations that would confine her. Hill notes that her exuberant laughter has often been deemed inappropriate, particularly in the strict religious environment of her childhood.

“I don’t try to always come up with ‘da-da,'” she explains, “I’m not always trying to ‘gotcha,’ but I’m gonna find the joy. That is something that no one can take from me.”

Hill links this devotion to joy with her commitment to service, especially for those dealing with trauma or hardship: “I’ve been very blessed to have a charmed life, not filled with a lot of trauma. So I really try to be of service to people who have had a lot of discourse and trauma, and I try to infuse some joy and some color and some laughter.”

From vintage frames to cultural preservation

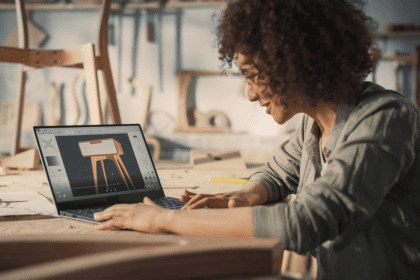

Hill’s signature chair sculptures, which transformed vintage American-made steel frames with intricate, colorful weaving pattern, exemplify her philosophy. These pieces, which started as a pandemic project, quickly gained attention from prominent collectors and eventually Bloomingdale’s.

“A big part of this early work, and still is, is upcycling,” Hill explains. “They’re American made because they’re steel. And then reinventing them with this weaving that’s very niche and specific to my style.”

The chairs carry cultural and familial significance, with weaving patterns inspired by “true, indigenous, South American, Tunisian, Moroccan, East African, South American weaving.” Some of her most meaningful pieces incorporate frames from her grandmother’s lawn chairs, connecting generations through craft.

“I think it comes down to these things choosing me to tell stories and continue to tell stories about how powerful we are,” Hill reflects. “Our indigenous footprint is everywhere, and now, more than ever in a season of erasure or attempted erasure, it’s in my work. You’re going to feel it in the weaving, you’re sitting in my grandmother’s prayers.”

The path forward

As the first Black furniture designer carried by Bloomingdale’s, Hill has achieved historic recognition, but she remains focused on authenticity and joy rather than external validation.

“I’m always going to color outside the lines, and I also make the crayons,” she declares, reinforcing her commitment to defining her own path.

For Hill, design is not merely about aesthetics—it’s about honoring heritage, challenging limitations, and creating spaces where authentic self-expression can flourish. Her maximalist approach stands as a vibrant alternative to minimalist trends, reminding us that sometimes more truly is more—more joyful, more meaningful, and more authentically human.