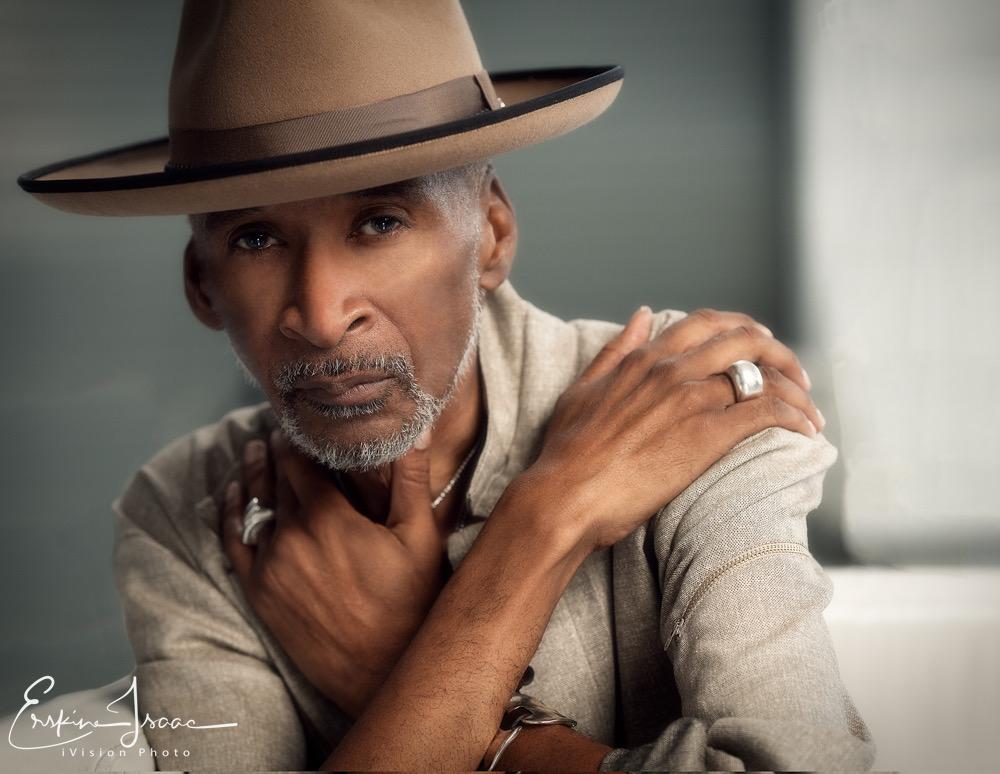

The modern music industry presents itself as a paragon of diversity, playlists that merge genres, executives who tout inclusion initiatives, award shows that celebrate voices from every community. Behind this carefully cultivated image, however, lies a history of rigid segregation that continues to influence how music is marketed, distributed, and valued. Few individuals have navigated these hidden boundaries as successfully, or can speak about them as candidly, as Angelo Ellerbee.

For more than four decades, Ellerbee has represented some of music’s most transformative voices, from Whitney Houston to DMX, Mary J. Blige to Alicia Keys. Through his company Double XXposure, he has shaped not just how these artists are perceived by the public but how they understand themselves. Yet his newly released memoir, “Before I Let Go,” reveals that his most significant accomplishment may be the barriers he dismantled along the way, barriers that many pretend never existed.

“Back in that day and time, there was a separation of what was Black music and what was mainstream music,” Ellerbee explains, describing his early years at Chrysalis Records in the 1980s. “I always thought music was music, but it was like society, there was segregation within the music industry.”

This segregation manifested not as vague cultural bias but as explicit policy. “You could not, as a Black person, go inside of the mainstream marketing meetings,” Ellerbee recalls. “You could stay on your side of the street with your Black music.”

Explicit industry segregation

The modern discourse around music industry inequity often relies on coded language and abstract concepts. Terms like “urban” have long served as convenient euphemisms for “Black,” while discussions of algorithmic bias in streaming services provide technical distance from more uncomfortable conversations about racial valuation of art.

Ellerbee’s account strips away this veneer. His experience at Chrysalis Records in the early 1980s reveals segregation that was neither subtle nor apologetic.

When recruited to Chrysalis for what seemed to him the surprisingly substantial salary of $40,000 annually, Ellerbee encountered immediate hostility from Frances Pennington, then the company’s Vice President. “If Frances Pennington didn’t hate every inch of my guts,” he recalls with characteristic directness. The underlying assumption was clear: “Black people are not supposed to be intelligent, they’re not supposed to be smart, they’re not supposed to know their craft.”

The expectation that Ellerbee would simply follow orders rather than contribute ideas reflected not just individual prejudice but a structural understanding of how Black executives should function within predominantly white companies. “You’re just going to come and follow me,” Ellerbee summarizes the unspoken expectation.

His response was unequivocal, “Angelo Ellerbee is not the one that just followed you. My mother created a leader, and that’s what I was going to do.”

When assigned to the Black music division, Ellerbee found himself literally segregated into a different physical space from his white counterparts. “It was a cubicle. I wasn’t sitting in no cubicle,” he insists, recounting his refusal to accept this physical manifestation of the company’s racial hierarchy.

Instead, Ellerbee went to the executive floor, where he encountered a “big, tall German guy” who turned out to be Chrysalis’s co-chairman. After introductions, the chairman offered Ellerbee office space on the executive floor, a radical breach of the company’s unwritten but rigid racial geography.

“That didn’t sit well with those people on that floor, neither did it sit well with the people downstairs,” Ellerbee notes. Yet this physical positioning became symbolic of his broader refusal to accept the industry’s segregated structure.

The true test came when Ellerbee was invited to attend mainstream marketing meetings, spaces explicitly designed to exclude Black executives. “I went to one particular meeting, and it was colder than a refrigerator,” he recalls. “They said, ‘You’re in the wrong meeting.’ I said, ‘No, I was invited to this meeting.'”

When asked to present ideas for promoting pop artist Pat Benatar, Ellerbee’s suggestions received approval from company leadership, creating visible discomfort among those accustomed to racial exclusivity in decision-making. The unspoken questions hung in the air, “How is this Black man going to come up in my white meeting, my mainstream media, and start to dictate to me what needs to be happening with my pop artists?”

From basement to boardroom

Ellerbee’s journey through the music industry’s racial landscape began not in corporate offices but in his mother’s basement in Newark, New Jersey. After working with Grammy-winning musician James Mtume, Ellerbee decided to launch his own public relations firm, despite having virtually no resources.

“I was flat broke, didn’t know anything about where to get money from,” he recalls, “but I was full of vigor, and I was full of ambition.” With a repurposed dining room table as his desk and only a basic telephone without call-waiting capabilities, he began building what would become Double XXposure.

His initial client base consisted largely of dance and club artists like Jocelyn Brown and Sybil, performers who “were totally unaware of what a publicist was.” This educational component became central to Ellerbee’s approach: helping artists understand not just their public image but the industry mechanisms designed to categorize and often limit them.

After leaving Chrysalis, Ellerbee’s understanding of industry racism informed his strategic decisions. When seeking office space for his expanding company, he recognized that his race would be an obstacle with certain landlords. “I was smart enough to know that I couldn’t bring my Black body up in this white establishment,” he explains regarding a rental opportunity in an Italian-owned building.

His solution utilized his full name: Angelo Antonio Ellerbee. “I called my Italian friend, who was a lawyer, his name was Ed Toptani. He went upstairs,” Ellerbee recounts. “I signed the lease for seven months under the name of Angelo Antonio.”

When the landlord eventually met Ellerbee in person, the reaction confirmed his suspicions. “He says, ‘I think I’m in the wrong office. I’m here to meet Angelo Antonio.’ I said, ‘Here I am, in living color.'” Ellerbee adds, “This man must have turned colors because he had absolutely no understanding that I was Black, but I signed it for seven years.”

This incident illustrates Ellerbee’s pragmatic approach to systemic racism: recognizing its existence, anticipating its manifestations, and finding ways to circumvent rather than directly confront it. This strategy, using the system’s biases against itself, would inform how he would later guide artists through similar barriers.

The communal response

Rather than merely adapting to the industry’s segregated structure, Ellerbee worked to create alternative pathways for talent development, particularly for Black artists and professionals. His basement operation became an incubator for developing not just artists but future industry executives.

“I had nothing but interns because I had no money,” Ellerbee explains of his early operation. One of those interns was Vincent Herbert, who would later discover Lady Gaga and produce for artists like Destiny’s Child and Toni Braxton.

“Vincent used to come, and he used to take my mail to the post office, sweep up the basement floor,” Ellerbee recalls. “While I was feeding them, particularly for Vincent, I was feeding him the wherewithal on how to be successful in the music industry. Well, as time goes on, I think he could teach me some things at this particular point.”

This approach, creating informal mentorship within marginalized communities, represents a common response to institutional exclusion. Unable to access established pathways, Ellerbee and his contemporaries built parallel structures for knowledge and opportunity sharing.

“We all, as a community working together, trying to make a difference in our community, wanted to show the world that we have the extra ingredients to be great,” Ellerbee explains. “Not just to be great, but to be greater, not just to be greater, but to be the greatest that we wanted to do in our chosen professions.”

This collective ambition extended beyond individual success to encompass community advancement, a recognition that within a segregated industry, individual breakthroughs must translate into expanded opportunities for others.

The relationship crucible: Mary J. Blige

Ellerbee’s understanding of industry racism informed not just his business strategy but his approach to artist development. Recognizing that Black artists faced different challenges and expectations than their white counterparts, he developed methodologies specifically designed to prepare them for these disparities.

His work with Mary J. Blige illustrates this approach. Their relationship began inauspiciously, with Blige arriving “an hour and a half late” to their first meeting. “My mind was, ‘I got paid already,'” Ellerbee recalls. When Blige addressed him casually, asking “Is Angelo here?”, his response established clear expectations: “I said, ‘Are you speaking about Mr. Ellerbee?’ She said, ‘Whatever.’ I said, ‘No, I ain’t going to be too many ‘whatevers.'”

This insistence on formality and respect, “I am Angelo Ellerbee, I prefer Mr. Ellerbee”, reflects Ellerbee’s understanding that Black artists, particularly from disadvantaged backgrounds, needed different preparation for an industry that would hold them to higher standards than their white counterparts.

“How you start is how you finish,” Ellerbee explains. “You want respect, you can’t go raising your child at 15 years old, you’ve got to raise them from infancy so they respect and they understand who you are.”

The second meeting established a new foundation, “The next day, she was two hours early, and it was smooth sailing, smooth sailing from there on.” This reset illustrates Ellerbee’s philosophy of relationship building that acknowledges but doesn’t excuse the circumstances that shape artists’ behaviors.

By insisting on standards while still accepting the artist, Ellerbee created developmental relationships that prepared performers for an industry where second chances were rarely extended to Black artists labeled “difficult.” His approach combined accountability with understanding, recognizing the environments his clients came from while preparing them for the environments they would need to navigate.

The unseen humanity: DMX beyond headlines

Perhaps nowhere is the intersection of industry racism and artist representation more evident than in Ellerbee’s account of working with DMX, the chart-topping rapper whose public image often emphasized his legal troubles and struggles with addiction.

“I really think that the impression of DMX is that he didn’t give a damn, that he had an addiction, he didn’t care, and that is the wrongest story for anyone to ever believe,” Ellerbee states emphatically. “I worked for him for five years—six years. I started as his publicist, and then got into his management, the president of his record label, Bloodline.”

The DMX that Ellerbee knew was deeply spiritual and philanthropically committed. “Every time I would say to him, ‘Man, did you pray today?’ He was like, ‘No, man, can we pray?'” Ellerbee recalls. “For five years, every Friday, he would call me up and say, ‘Did you pay my tithes?'”

This commitment extended to substantial charitable work largely invisible to the public. “This is what this man did, churches all over the world, he would give donations, large donations,” Ellerbee explains. The rapper’s annual Christmas giving was particularly significant: “Every year, he used to host about five to a thousand families that did not have Christmas.”

The contrast between this reality and public perception reflects how industry racism shapes media narratives about Black artists. While white performers with similar struggles often receive redemptive coverage emphasizing their artistic contributions and humanitarian efforts, Black artists like DMX frequently see their troubles amplified and their positive contributions minimized.

“People always want to judge a book by its cover,” Ellerbee observes. “No, you need to read those pages because the pages of his life, if somebody wrote the truth about his life, you would see that he was an incredible, incredible human being.”

The purpose behind “Before I Let Go”

While Ellerbee’s memoir contains valuable insights about industry racism, his stated purpose extends beyond exposing these historical patterns. When asked about the book’s title, he pivots to broader social concerns that clearly weigh heavily on him.

“I’ve been so blessed, man,” he begins. “As I go through life, I’ve seen so many disappointments with those incarcerated, with the homeless, with the HIV and AIDS victims, it bothers me.”

These concerns connect to his observations about systemic inequities: “Incarcerated, we have a president that is, a President of the United States of America has 34 counts, federal counts against them, but a brother, brown or Black, can come out of jail, and they perish, they can’t do anything because they have all these legal things that are against them.”

For Ellerbee, these disparities reflect the same systemic racism he encountered in the music industry, different manifestations of the same fundamental inequities. His memoir aims to address these broader concerns by showing how even celebrated figures overcame similar obstacles.

“The book is to set an example,” he explains. “I take the Mary J. Bliges, the Alicia Keys, the Dionne Warwicks, all these people went through some of the same things that these people laying in the streets and at a disadvantage did.”

By connecting celebrity narratives to broader social struggles, Ellerbee hopes to reach readers facing similar challenges, “‘Before I let you go,’ I want you to understand that you’re one of God’s children. ‘Before I let you go,’ I want you to understand that you can come from incarceration and that you can be great.”

In this way, Ellerbee’s memoir becomes not just an industry exposé but a broader social document, using his unique vantage point at the intersection of race, entertainment, and commerce to illuminate patterns that extend far beyond recording studios and concert venues.

“I know everybody thinks that because I’m in the entertainment industry, I’m writing a book about, no, I’m writing a book about everybody,” Ellerbee insists. “The book is for everybody, it’s for everybody to learn by and to grow by and to understand they get chances and to be humanistic across the world.”

Ellerbee’s memoir stands as testimony to an industry whose racial reckonings remain incomplete, where progress has occurred but fundamental structures of valuation and opportunity continue to reflect America’s broader racial hierarchies. By naming these patterns explicitly rather than through euphemism, Ellerbee’s account provides valuable context for understanding not just music history but contemporary debates about representation, algorithm bias, and genre classification that continue to shape how different artists’ contributions are recognized and rewarded.