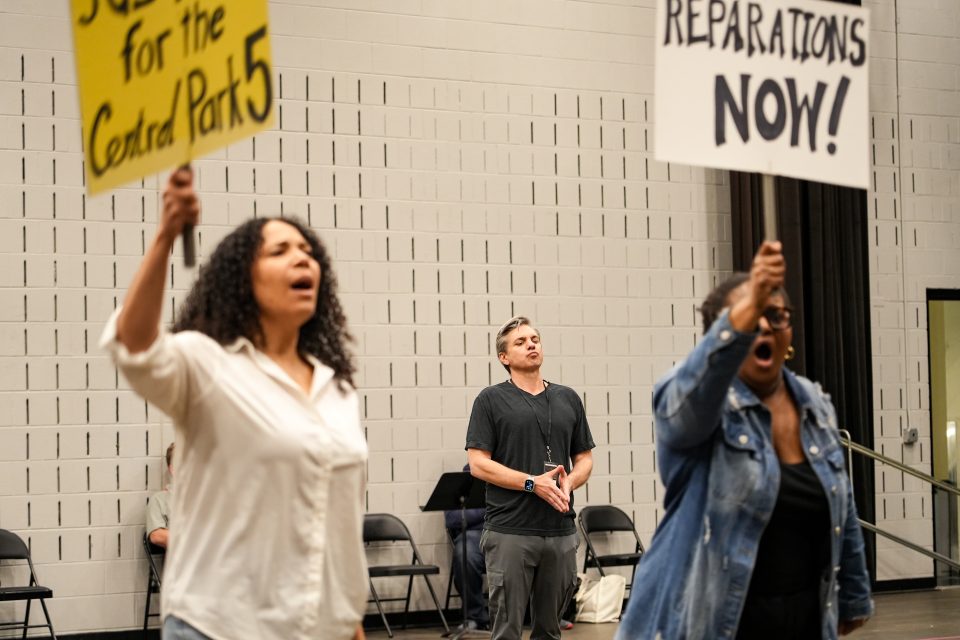

Chaz Williams-Ali represents a new generation of classical performers breaking barriers and expanding representation in traditionally exclusive spaces. The acclaimed tenor currently stars in the Pulitzer Prize-winning opera “The Central Park Five,” portraying Raymond Santana, one of the five young men wrongfully convicted in a case that continues to resonate in American culture.

With an impressive resume that includes performances at the Metropolitan Opera, English National Opera, and Washington National Opera, Williams-Ali brings extraordinary talent and cultural insight to this groundbreaking production. The St. Louis native, who began his journey at Central Visual and Performing Arts High School before studying at the University of Iowa School of Music.

What emotions surface when thinking about starring in an opera based on the Central Park Five case?

Opera is a very unique form of storytelling, ultimately it is what we are, storytellers. I think that’s not just about artists. I think we, as humans, it’s baked into our DNA, into our anthropology to be storytellers. And so opera is just a unique form of that storytelling.

Where I grew up, I wasn’t really exposed to a ton of opera in my background. I think if someone sees the name Central Park Five, which they may recognize from either being around when it happened, or the Netflix series, When They See Us or documentaries, that might draw some people in to say, “Okay, I know what their story’s about,” and then when they get there, they’re going to see themselves represented on stage, which is a rarity in our genre, sometimes.

They get to see a uniquely American, a uniquely 21st century story with relevance to today being told in a vehicle, or, as our director Nataki likes to use the term container, being told in a container that is different. One of the things that I think makes opera so unique is that you have not only the what but you also get to feel the how and the why in the music.

How would you describe your role as Raymond Santana and the challenges of bringing his story to life through opera?

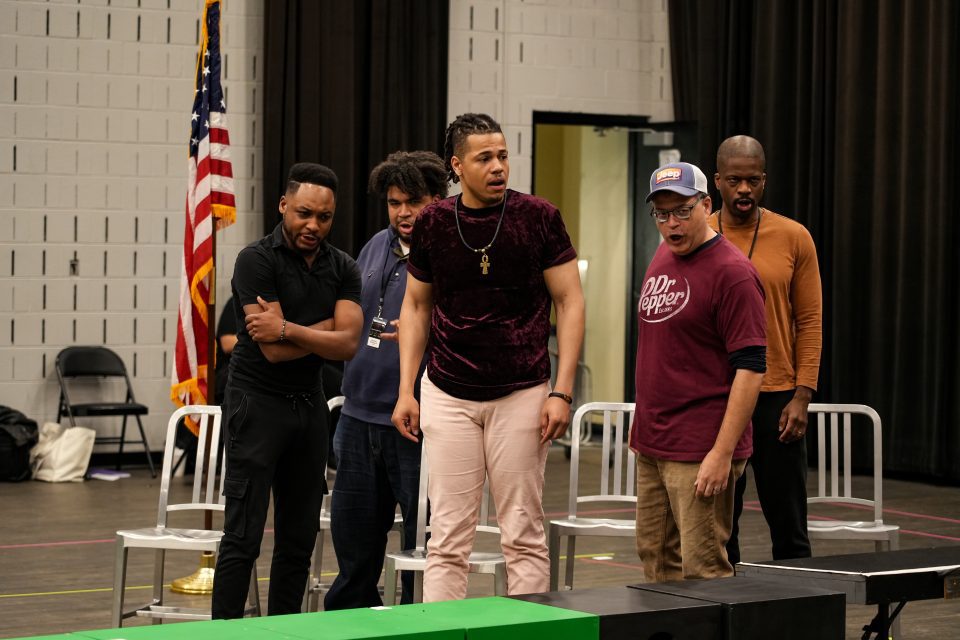

I am given the huge task of playing Raymond Santana, a young man who is at the intersection of Latinx community and African American community in Harlem. I think it’s always challenging to play people that are still alive because you have footage of these people and you have social media.

Looking at a story like this, that has so much relevance you have to have multiple brains. You have Chaz, the actor who is trying to really tell this story, and Anthony Davis is a musical genius, and so you have to have Chaz, the musician who knows all this complicated music, and what’s going on, and you have to be together with the orchestra, with your cast and everything.

I’m a father of 3 children, 2 of which are boys, and so for me to imagine my sons going through this. There were times in rehearsal where I had to just step away from the process, because I can’t allow myself to go all the way there, because then I’m not able to tell the story because Chaz, the performer, is too emotional. So you have to find that balance and find that separation so that you leave space for the audience member to insert his or herself into that position. If there’s no space for the audience to put their emotions, then they don’t really get a chance to experience that journey with you.

How did you discover your passion for opera and acting?

My mother is a very talented choreographer and theater director, so I grew up on stage. My dad is a very accomplished and very talented drummer who’s played with The Drifters, and Johnny Hooker and Zakiya Hooker and Lady Bianca. On his side I had a lot of music, on mom’s side, I had a lot of theater and so I’ve been able to kind of blend those 2 together in something, opera.

Anthony Davis allows me to stretch those musical muscles that live in the jazz world and in the Blues world and in the funk world, growing up doing that stuff with my dad. A little side story, I’ve had the mission since I was 9 years old to go to Hitsville, so my very first day, I made the trek over to Hitsville, and I was able to scratch that itch. Being able to be in that building with that history informed my rehearsal process, because I was like, these guys grew up on that stuff, too.

Opera was one of those things that came later in the game for me when I was in high school. I went to a performing Arts High School, and I was able to link up with Opera Theatre Saint Louis for their High School students program. We went to see Verdi Traviata when I was 18, and that was a life changing experience for me, because that pushed me into a path to say, Okay, well, if opera is that, then I can do that, then I want to do that because that is musical storytelling, I believe, at its finest.

For those who have never experienced opera, how would you describe what they’ll experience in this production?

First of all, I believe that our experience, as people of color, is the human experience. It’s not separate from everybody else’s story. Our stories are all told together. We are all pieces of the puzzle and anybody that’s ever done a puzzle knows that a lot of times the part of the puzzle that doesn’t have the clearest picture is the hardest part of the puzzle to put together. And that’s the part of the story that we’re trying to tell.

When you go to an opera, you can see yourself on the stage, and in this opera in particular, for people of color here in the D or anywhere nearby. I know Chicago’s not far, I know a lot of places not far, come check us out. It’s interesting to see elements that we all grew up with, I don’t want to spoil anything, but there are dances that I know everybody from the cookout knows how to do, that’s on the stage. There are imagery, and people wearing Run-D.M.C. Hoodies and things that you really can identify with being told in this way.

I think that’s a special thing to do, and I think that if you come in with an open mind, it may take you 5 to 10 min to get into the world, to get into the idea that we’re not talking to each other, we’re singing to each other, but when we sing to each other, that is how we are communicating. Once you get past that hurdle, once you allow yourself that suspension of disbelief, then you can really bask in the music and bask in the story, and bask in the way that we’re relating to each other in this traditionally hoity-toity art form of opera. But when you see these brothers interacting with each other, you see, “Oh, man he dapped him up like I dap up my barber, but he’s singing opera.”

How would you introduce opera to someone who has never experienced it before?

I would say that opera itself is a genre of music, but it is not a monolith, just like rap or hip hop is not a monolith, because you can be somebody who’s really into hip hop, and you can say, Man, I’m super into hip hop, and somebody else at the barbershop can say, Man, I’m super into hip hop, but they don’t like the same stuff. One of them is talking Sugarhill Gang and Run-D.M.C. and Flavor Flav, and the other person is talking about Lil Yachty and Jeezy, and these young guys. And somebody else is like man, it was all about Pac and Biggie and Bone Thugs-n-Harmony in the 90s, and they’re like, no man, it’s Jay-z and Kanye.

Opera’s the same way. There are so many different ways inside of the vehicle of opera to tell a story, and this is one of those ways. This opera is a chance to see our culture, to see the way we interact with each other, using the style of communication of opera. Being able to see that is really, really cool, and it’s something that you don’t get to see every day, and it’s worth coming to check out.

What would you say to young people about entering spaces that traditionally haven’t welcomed people who look like us?

I would say that most of the time people don’t believe that they can do something until they see somebody that looks like them do it. And I would like to point everybody back through the last century to show that when we, as people of color, decide to do something, typically, we rise to the cream of the crop. When we decided to get into golf, we didn’t just get into golf in the middle, we gave you the best golf of all time. When we decided to get into tennis we didn’t get in the middle, we decided to give you the greatest tennis players of all time, the greatest pair of sisters to ever play the same sport of all time.

When they finally broke the color barrier, Jackie Robinson didn’t come in and say, No, man, I’m happy to be in the middle, he became one of the greatest second baseball players of all time. When we decided to get in the opera, we didn’t get in the middle, we had Marian Anderson. We had Leontyne Price. We had Jessye Norman who decided to do it at the highest levels of all time. That’s what we do, and this is another mountain for us to climb.

This is another door for us to open, and I believe once you come out of the darkness you should turn on the light for your friends. That’s a quote from another Detroit Group Commission with Fred Hammond and the boys. When you come out of the darkness, turn on the lights for your friends, and that’s what we’re here to do. We’re here to turn on that light and to show people that anything is possible, so many things that you didn’t think is possible, is not only possible, but probable for you at the intersection of preparation and opportunity.

If you could prepare yourself, and if you can get yourself ready for it, and if you can see it and put in the work then you could do something like this, because people don’t wake up in the morning and just sing opera. It takes a lot of training, it takes a lot of dedication. It takes a lot of taking care of your mind, taking care of your voice, taking care of your body, taking care of everything. But if you are willing to put in that work. This is another avenue and another vehicle to experience storytelling.