The psychological patterns that define America’s overlooked caregivers

Across American households, millions of women navigate adult relationships while carrying invisible emotional baggage accumulated during childhood. These eldest daughters, thrust into premature responsibility, often discover that their early caretaking roles have fundamentally shaped their approach to love, partnership, and self-worth in ways that can prove both empowering and limiting.

Recent psychological research indicates that approximately 40% of eldest daughters report feeling overwhelmed by family responsibilities that began before age 10. This phenomenon, increasingly recognized by mental health professionals, extends far beyond simple birth order dynamics, creating lasting patterns that influence everything from career choices to romantic partnerships.

The psychological framework that develops in these early years often persists well into adulthood, manifesting in relationships where these women excel at nurturing others while struggling to advocate for their own needs. Understanding this dynamic has become crucial for therapists, relationship counselors and the women themselves as they work to establish healthier boundaries.

The early formation of caretaker identity

Family dynamics in larger households frequently position eldest daughters as secondary parents, a role that typically emerges organically rather than through deliberate assignment. These young girls learn to anticipate needs, mediate conflicts and provide emotional support for younger siblings while simultaneously managing their own developmental challenges.

This premature assumption of adult responsibilities creates a psychological blueprint that values service to others above personal fulfillment. Many women describe feeling most comfortable when they are needed, finding their sense of worth intrinsically tied to their utility within family systems or romantic relationships.

The pattern often reinforces itself through positive feedback loops, where family members come to depend on the eldest daughter’s emotional labor, inadvertently reinforcing behaviors that may later prove problematic in adult relationships. These women frequently report feeling valued primarily for what they provide rather than who they are as individuals.

Professional and personal manifestations

In professional settings, former eldest daughters often gravitate toward helping professions or roles that require significant emotional intelligence and interpersonal management. While these career paths can prove fulfilling, they may also perpetuate patterns of over-giving that originated in childhood family dynamics.

The workplace often rewards the same behaviors that characterized their early family roles: anticipating needs, managing conflicts and taking responsibility for group harmony. However, this professional success can mask underlying issues with boundary-setting and self-advocacy that become apparent in more intimate relationships.

Many women find themselves excelling in professional environments while struggling in romantic partnerships, where the same caretaking behaviors that brought career success may create imbalanced dynamics. The transition from being valued for competence to being loved for intrinsic worth often proves challenging for those accustomed to earning affection through service.

Romantic relationships and boundary challenges

Adult relationships present unique challenges for women who learned early that love requires constant effort and anticipation of others’ needs. Many report feeling most secure when partners depend on them, unconsciously recreating familiar dynamics where their worth stems from indispensability rather than mutual affection.

This pattern can manifest in relationships where these women consistently prioritize their partner’s comfort over their own needs, often without conscious awareness of the imbalance. The difficulty lies not in their capacity for love and care, but in their ability to receive the same level of attention and consideration.

Mental health professionals increasingly recognize that successful relationships for these women require intentional work to develop comfort with vulnerability and receiving care. The challenge involves learning to distinguish between healthy interdependence and the problematic patterns established during childhood.

The psychological cost of perpetual responsibility

The mental health implications of carrying excessive responsibility from a young age extend beyond relationship difficulties. Research indicates that eldest daughters show higher rates of anxiety, perfectionism and difficulty with emotional regulation compared to their younger siblings.

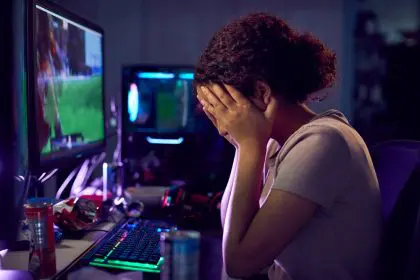

The constant state of vigilance required to anticipate family needs often creates chronic stress responses that persist into adulthood. Many women describe feeling unable to fully relax, always scanning for potential problems or unmet needs in their environment.

This hypervigilance, while adaptive in chaotic family systems, can prove exhausting in adult contexts where such intense monitoring is unnecessary. Learning to recognize when this response is appropriate versus habitual represents a crucial step in psychological healing.

Therapeutic approaches and healing strategies

Mental health professionals working with this population emphasize the importance of recognizing these patterns as adaptive responses to challenging circumstances rather than personal failings. The same skills that enabled survival in demanding family situations can, with conscious effort, be redirected toward healthier expressions of care and connection.

Effective therapeutic interventions often focus on developing comfort with receiving care, setting appropriate boundaries and distinguishing between chosen acts of service versus compulsive caretaking behaviors. These women typically benefit from approaches that validate their strengths while addressing the underlying patterns that may limit their relationships.

Group therapy settings prove particularly beneficial, as many women discover they are not alone in their experiences. The opportunity to connect with others who share similar backgrounds can provide validation and practical strategies for implementing healthier relationship patterns.

Redefining strength and vulnerability

The journey toward healthier relationships often requires redefining concepts of strength and vulnerability that were established during formative years. For many eldest daughters, vulnerability feels dangerous because their early safety depended on maintaining competence and control.

Learning to view vulnerability as a form of strength rather than weakness represents a fundamental shift that enables deeper, more authentic connections. This process typically involves gradual exposure to situations where they can practice receiving care without feeling obligated to reciprocate immediately.

The goal is not to eliminate their natural capacity for nurturing others, but to develop a more balanced approach that includes space for their own needs and desires. This balance allows for relationships built on mutual care rather than one-sided service.

As more women recognize these patterns and seek support in addressing them, the conversation around eldest daughter experiences continues to evolve. The path forward involves honoring the strength developed through early challenges while creating space for the softness and vulnerability that enables genuine intimacy.

Their journey toward emotional freedom benefits not only themselves but also the partners and children who will experience more balanced, authentic relationships as a result of this important psychological work.