When I think about vinyl records, I reminisce about 70’s house parties in somebody’s mama’s basement. I recall record players and Bose speakers, pulsating purple strobe lights, and dancing slowly, and way too close, with cute boys sporting afros. The scent of that forbidden green herb would ultimately permeate the space and we’d sip on grape flavored Boone’s Farm while immersing ourselves in the sounds of Earth Wind and Fire, Chaka Khan and Parliament. Everything was “copasetic,” as we would say.

As I matured, those house parties became a thing of the past, and because of technological advances, so did turntables and vinyl. Like other African Americans who came of age in the 70s, my cultural identity was to a large part shaped by those experiences with vinyl records.

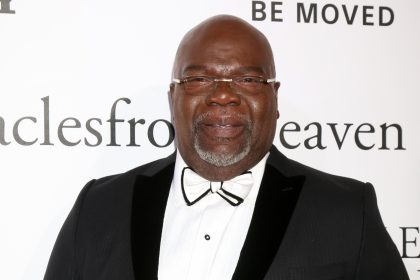

Jonathan Blanchard believes that vinyl records are just as relevant to the African American community today as they were back then. His new record store, JB’s Record Lounge, recently opened to the public in historic West End, Atlanta. While this venture may prove to be economically timely, due to a burgeoning demand for vinyl records amongst both young and older demographics, his ambitions are more directly tied to stimulating consciousness in the African American community while using the record store and music as a catalyst for change.

According to Blanchard, the store is a “dream born out of necessity” derived from his “love of vintage vinyl” and his experiences as a musician. As a full time performer, Blanchard began to realize that there are few, if any, venues for Black indie artists to perform their work, and even fewer distributors of African American music who look like him.

He said, “I recall walking into local eateries, and seeing posters for concert series with artists I’d never heard of. I would ask myself, ‘Where are our venues?’ The bigger question, however, is who is controlling and exploiting African American music, culture, and labor? I fear that in our ambition to dissolve into the dominant culture, we have offered up our institutions as ransom — be it music, music halls, the music circuit, once referred to as the ‘chitterling circuit’ and in other industries.”

Blanchard’s primary objectives are to sell product, while providing an outlet for indie artists from the community to perform, and to provide a space for progressive Black people to network.

The record store is located at 640 Evans Street. This local business emerged as a partnership between Blanchard and Jay White, owner of 640 West Community Café. While Blanchard occupies a separate space in the café, he has access to the café’s stage and other amenities and the two will collaborate on events and other forms of entertainment. Blanchard believes that this relationship will benefit both parties involved and the community at large.

“I expect JB’s to provide an undeserved community with a fresh yet familiar form of entertainment,” said Blanchard who believes records “make people stop and talk to one another, and talking to one another forms community bonds.” -keven lynch