Royce of suburban Wilmington, Del., likens watching black reality television shows that beam social and familial dysfunction into living rooms every week to slowing down for a car crash. Royce, a commercial real estate executive, knows that what he may mentally devour could be stomach-churning, but he and others can’t help but crane their necks to get an eyeful of the twisted cultural wreckage anyhow.

“A couple of times a week I enjoy seeing people demeaned for their personal style and, sometimes, ‘ethnic’ features. I laugh at women portrayed as vapid, man-hungry gold diggers,” writes Tami Winfrey Harris, an African American writer from central Indiana in a story printed in Psychology Today. “I am entertained by a parade of ugly stereotypes: angry black women, dumb blondes, ‘spicy’ Latinas and dusky, hyper-sexed, buffoonish lotharios. Yes. I watch reality TV.”

Winfrey Harris and Royce are not alone.

The trash talking, weave pulling, wig snatching, fist-flying and other forms of pure buffoonery and histrionics — on shows where the cast members butcher the English language more than each other — makes for very watchable TV.

What’s the problem, Winfrey Harris essentially asks, about watching the wretched lives (many now call it “ratched”) and poor choices of other people after a hard week at work?

“Admit it: you like a little guilty pleasure,” Winfrey Harris continued.

But there’s plenty wrong with it, says Jennifer Pozner, who authored Reality Bites Back: The Truth About Guilty Pleasure. Pozner proffers that reality TV is responsible for reinforcing racial and ethnic stereotypes, negatively impacts women, and people of color and will have a detrimental effect on a generation of viewers coming of age. She boldly opines that reality TV is skewered to “court controversy” and, thus, boost ratings. And if producers have to submerge themselves and the cast members in the racial tropes cesspool to accomplish this objective, then they and the cast will gleefully do so for a paycheck and faux fame.

Psychologists decry the mindless behavior that mutates reality for the undiscerning, the ignorant and the impressionable young minds who are drinking in these tainted images.

“Programs like ‘The Apprentice’ routinely stereotype black participants,” psychologist Simon Rosemead wrote. “Black contestants are often portrayed as stormy and indolent fringe elements, while their white counterparts are portrayed as stable and industrious collaborators. Black reality TV contestants face discrimination at levels approaching those of everyday life.”

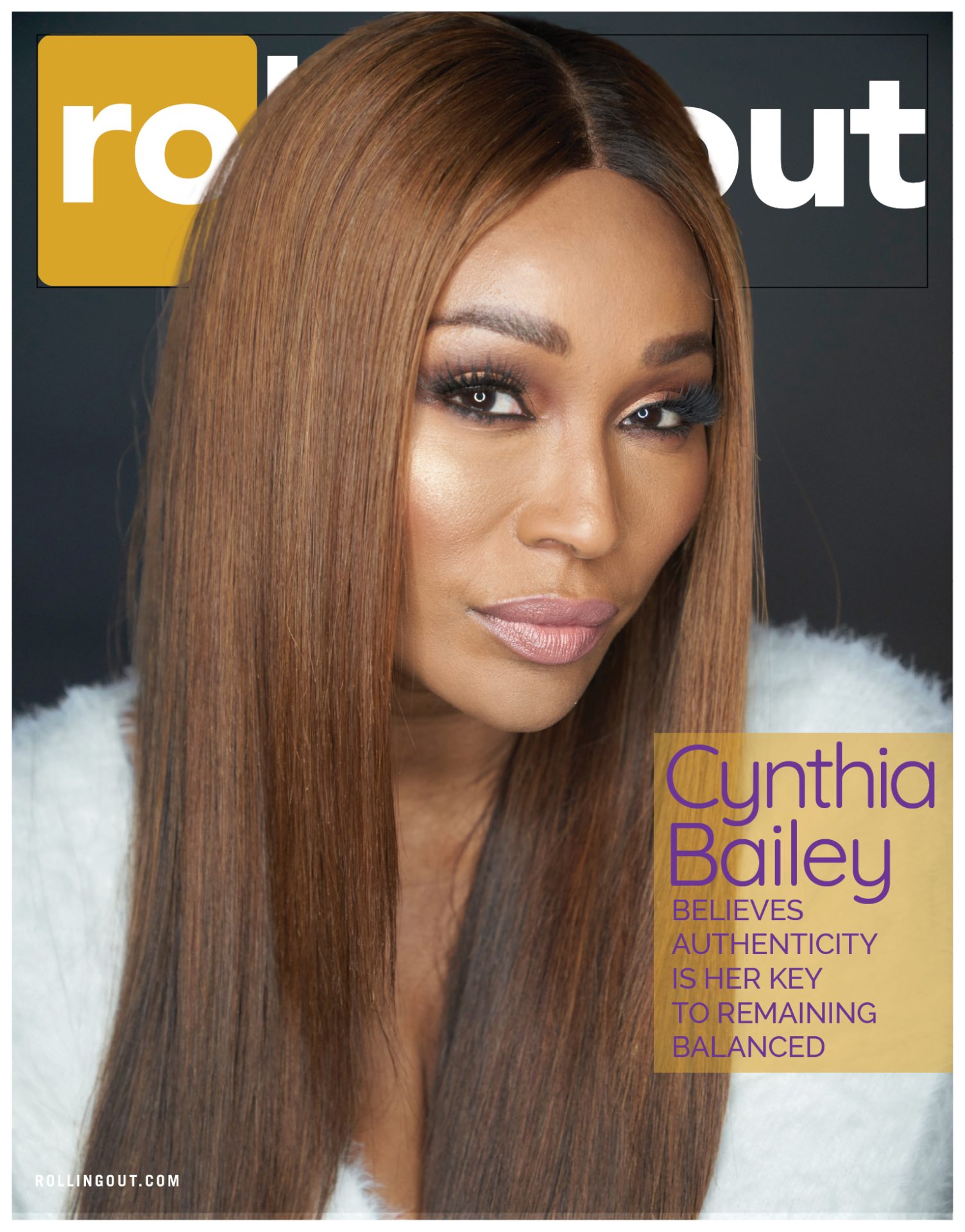

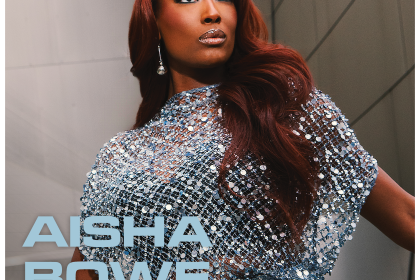

Black reality TV, in particular, illuminates a disturbing new formula that producers discovered for the reality TV genre: Put two or more headstrong and mostly black women in the same room — and let the fireworks begin. Everything from Oxygen’s “Bad Girls” to Bravo’s “Real Housewives” to the “Basketball Wives” franchise, the small screen is overflowing with black women who roll their eyes, bob their heads, snap their fingers, spit verbal poison in each other’s faces and otherwise reinforce the ugly stereotype of the “angry, uncouth, uncivilized black woman.”

Re-examine two shows in particular, VH1’s “Basketball Wives” and “Love & Hip Hop,” which feature the scorned ex-wives and baby mamas of rich NBA stars and rappers, as examples. No episode is complete without a catty confrontation or a threat to do bodily harm.

These shows get the highest ratings even as they are taken apart as horrific examples of how black women (in particular) are viewed.

The study cited the case of Omarosa Manigault-Stallworth, a black woman who criticized “The Apprentice” for stereotyping her and other black contestants.

“Producers edited footage to make Omarosa look like a self-involved diva,” said Rosemead, the study director of the 5,000 page report on the harmful effects of black reality TV. “Her allegations are not isolated. Reality shows often depict black female contestants as sassy and overly aggressive, and black male TV contestants often appear incompetent and lazy. They are minor characters who are often prematurely ousted from the TV workplace.”

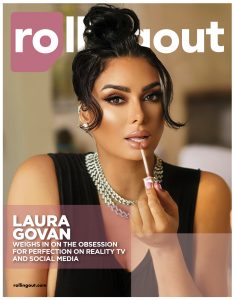

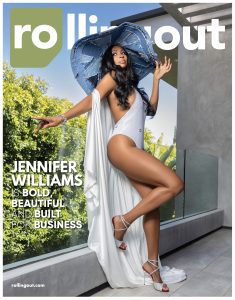

All of the shenanigans are bad enough. But when Evelyn Lozada walked across the table in the infamous scene to engage in a knuckle game with her adversary Jennifer Williams, some people had seen all they could take. Black female celebrities were among the most vocal — even as they watched:

Diahann Carroll: “What I see now on television for the most part is a disgrace, as far as how we’re depicted,” says Carroll, who was the first black woman to star in her own television show, “Julia,” in 1968. “I won’t and don’t watch it.”

Phylicia Rashad: The beloved TV, movie and theater thespian played Bill Cosby’s lawyer wife in the legendary ‘80s comedy, “The Cosby Show. She distinctly remembers what the late NBC executive Brandon Tartikoff predicted would happen after Cosby went off the air: “He said it was going to get much worse before it got better in terms of diversity,” she says. “He was right.”

Holly Robinson Peete: “Listen, there are plenty of white women acting a fool on television every night,” says Robinson Peete, the runner-up on last year’s “Celebrity Apprentice.” “But there’s a balance for them. They have shows on the major networks — not just cable and not just reality shows — about them running companies, being great mothers, and having loving relationships. We don’t have enough of that.”

Star Jones: The attorney and TV personality who also appeared on ”Celebrity Apprentice” launched a petition to encourage an embargo against “Basketball Wives.” Even the show’s executive producer, Shaunie O’Neal, ex-wife of basketball legend Shaquille O’Neal, had to try to mop up behind some of the mess that her show was creating.

Robinson Peete added that Caucasians are not nearly as embarrassed by reality TV shows, such as “Teen Moms,” “Jersey Shore” and “Mob Wives,” because there is a plethora of positive programming constantly streaming in to provide sufficient cultural counterpoints to offset any damage that could be inflicted by such shows.

Dr. Amber Tillman, an assistant professor of communication at Prairie View A&M University, agrees with Robinson Peete. Tillman said black women instinctively feel shamed by the negative depictions of them on reality television, whereas women of other ethnicities do not, because of our typically narrow representations. Perhaps this is why most black women seem outraged, while women of other races, including those on the aforementioned white reality TV shows, do not.

“[Nigerian writer] Chimamanda Adiche reminds us of the dangers of the single story,” Tillman told the online news platform theGrio in an interview. “When all we have is one story or one representation of us, everything we do is judged by that standard. Because there are so many representations of white women, when a single white woman does something negative, it is not representative of the entire race. We have so few stories, that everything we do becomes representative of everything we are.”

Reality shows provide plenty of examples of what not to do, but in rare moments they may also show us what works — for example, how to build a genuine friendship with someone you’re in competition with, how to stay strong in a stressful environment, or how to recover and remain resilient after failure. Unfortunately, some of the information blacks learn from reality TV is inaccurate and destructive. Many reality shows reinforce negative ethnic and gender stereotypes and promote conspicuous consumption, materialism and “wilding out” to attain instant fame.

Some celebrities believe that reality TV detractors should pump the brakes a little bit. There are redeemable properties in some reality shows that are being overlooked in this inferno of national urban debate.

“I like shows like ‘The Voice,’ cooking shows like ‘Top Chef,’ ” actress Elise Neal told rolling out. Neal is known for her roles on shows such as “Seaquest,” “The Hughleys,” “All of Us,” “The Cape” and “Ant Farm.”

“I love how these shows … highlight the talented people who would not have had a shot in the spotlight … and show me new dishes to cook,” Neal adds. But then Neal states what perhaps many African Americans are thinking, “I just want to see more balance. And there should be an even amount of room for scripted shows and sitcoms. We should all have a presence.”

And therein lies one of the most important pieces of the discussion: balance. Balance with negative and positive programming and balance between scripted and reality shows.

Producers who have struck gold with reality shows in general are not likely to stop. And citizens who are attention whores are not going to stop auditioning for roles on these shows. There’s too much money and fame to be made.

Besides, says Christopher Martin, an Atlanta-based actor, promoter and host of “ATL Profile,” some detractors are not looking at the big picture when they call for an outright embargo of black reality shows:

“I think you should look outside the box. These shows give people employment — producers, directors, cameramen and so on,” Martin writes. “They offer a lot of opportunity for people in the business. If you don’t like reality TV shows, don’t watch [them].”

But black Americans can’t help but watch — even as they half-cover their eyes in shame.