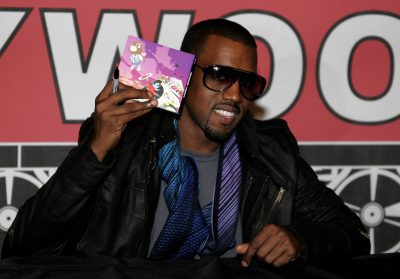

When it was announced that Kanye West was recruiting famed super producer Rick Rubin to assist him in finishing up his recently released sixth album Yeezus, fans and critics immediately began wondering what type of effect the bearded Jewish guy from Long Island would have on West’s creative output. The man responsible for producing some of the greatest hip-hop albums of the 1980s was teaming with hip-hop’s current caustic creative — what on earth would come of this?

It’s fairly easy to hear Rubin’s touches on Yeezus; the stark minimalism on tracks like “New Slaves” is very much a musical signature of the man who was known for giving himself credit as a “reducer” as opposed to a “producer.” But many younger hip-hop heads recognize Rubin as the guy who co-founded Def Jam Recordings with Russell Simmons and the guy who produced “99 Problems” for Jay-Z a decade ago; which is only the tip of the proverbial iceberg of his contributions to popular music over the last 30 years.

At Def Jam, Rubin was the producer that took hip-hop to platinum status. In 1985 and 1986, he produced three rap albums that proved to be game-changers commercially and artistically for the genre, beginning with LL Cool J’s debut album, Radio. The album announced the brash teenager from Queens as the newest solo superstar in rap, and helped finish what Run-D.M.C. started a year earlier; that is, tearing down any remnants of early hip-hop and its funk-and-disco sounds. Radio was a hard, aggressive, stripped-down album meant for rattling trunks–and it was “reduced” by Rick Rubin.

Shortly after that success, Rubin was let loose on hip-hop’s biggest group. Run-D.M.C. had been churning out rap hits for almost three years by the time Rubin and the Kings from Queens recorded their seminal third album, Raising Hell, and they’d already experienced crossover success with hit songs like “Rock Box” and “King of Rock” and an appearance at “Live Aid” in 1985. But Raising Hell catapulted the group to the forefront of pop culture, alongside the biggest acts of the day. The Rubin-produced LP was an instant classic and became hip-hop’s first multi-platinum album, catapulted by hits like “It’s Tricky,” “Peter Piper” and the ubiquitous Aerosmith cover, “Walk This Way.”

The third in his trifecta of ’80s rap classics was the debut rap album of three obnoxious white guys from Brooklyn. The Beastie Boys’ Licensed To Ill would go on to become the biggest-selling rap album of the 1980s, and on it, Rubin’s knack for merging hardcore hip-hop with classic rock samples and riffs reached its zenith. He only produced one album each for these three major hip-hop artists, but each one that he produced had a seismic affect on the genre.

Rubin would go on to work with the Geto Boys (they were signed to his Def American label following his departure from Def Jam), and as the 1990s progressed, he moved from producing hip-hop to producing a little bit of everything. His biggest successes were the Red Hot Chili Peppers breakthrough 1991 album Blood Sugar Sex Magik (as well as their 1998 comeback Californication) and country icon Johnny Cash’s acclaimed 1994 album American Recordings. But Rubin has worked with a wide array of other artists, including Tom Petty, Mars Volta, Weezer, Metallica, Linkin Park, Rage Against the Machine, Slayer and many more.

Rubin was brought in at the last minute to work on Yeezus, and the man who’s had a hand in so much of the last few decades of popular music admitted to the Daily Beast that the prospect of cleaning up that album was nerve-racking. “To me it seemed impossible what [Kanye] was asking,” he said. “I remember I wasn’t feeling that well that day, and I was thinking, ‘Is the music making me sick?’ I don’t feel good about this. We ended up working probably 15 days, 16 days, long hours, no days off, 15 hours a day. I was panicked the whole time.”

“There was so much material we could really pick which direction it was going to go,” he shared. “The idea of making it edgy and minimal and hard was Kanye’s. I’d say, ‘This song is not so good. Should I start messing with it? Can I make it better?’ And he’d say, ‘Yes, but instead of adding stuff, try taking stuff away.’ We talked a lot about minimalism. My house is basically an empty white box. When he walked in, he was like, ‘My house is an empty white box, too!'”

It’s easy to understand why a guy like Rubin can’t be bothered with dressing up a home. After all, if there’s anything he’s epitomized over all these years, it’s the idea that less is more.