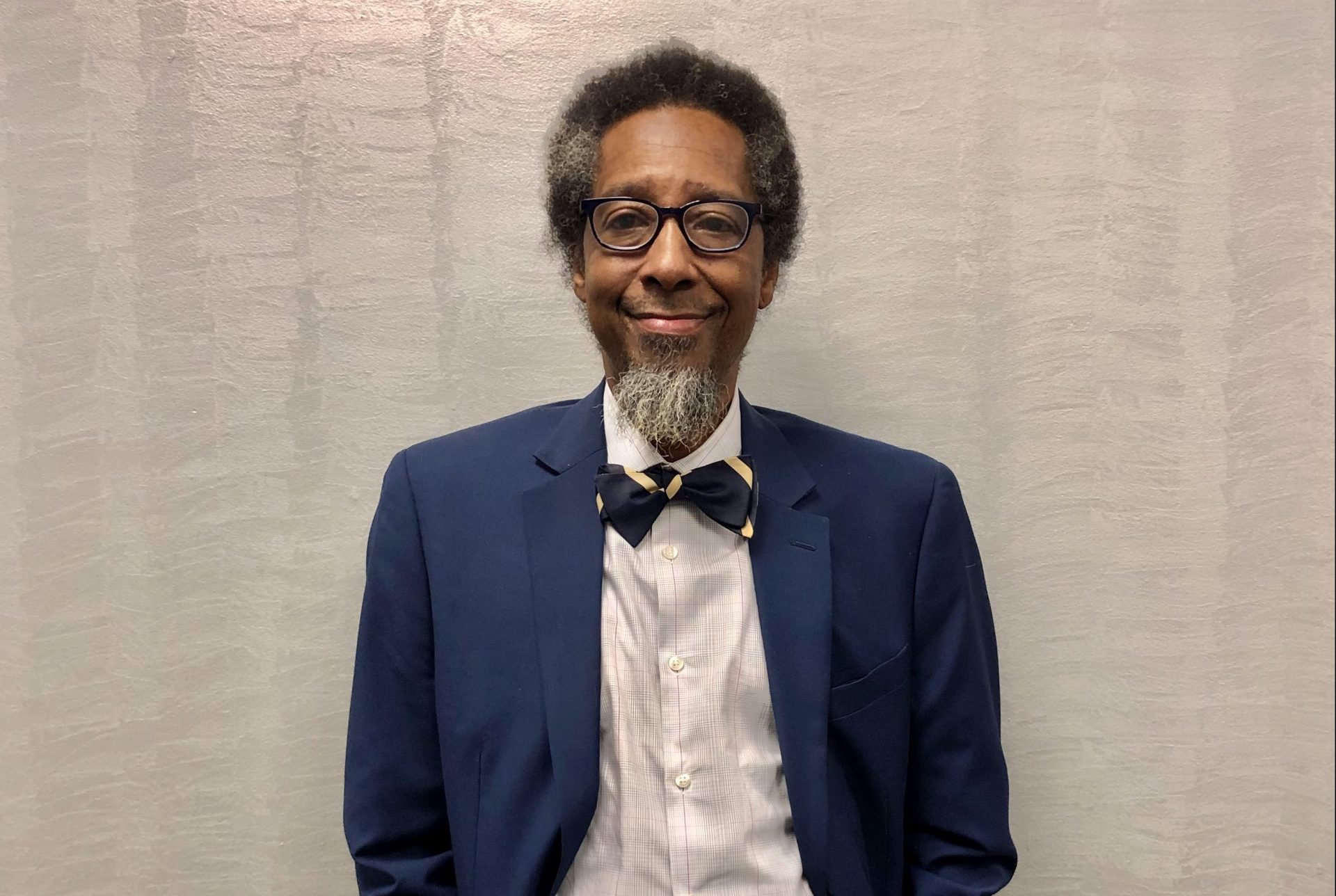

Atlanta City Council President Ceasar Mitchell, like most in the African American community, finds the growing pipeline of black males from high school to the prison-industrial complex highly disconcerting, if not disgusting.

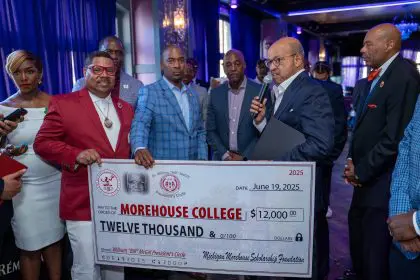

During his visit to the Black Male Summit at his alma mater Morehouse College recently, Mitchell discussed the inevitability of black male dropouts winding up intertwined in the legal and penal systems. For example, Fulton County 440,000 people go through our system, and of that 89 percent of them were African American. And that system in our adult system is mirrored in our juvenile system. The common denominator for all of those people on the adult side and the juvenile justice side is the dropouts. So 80 percent of folks who go through our system are dropouts. About 70 percent read on a third grade level.

Mitchell believes the seeds of dropping out are planted when students are toddlers. And that is where the rectification of this deplorable condition can commence.

“A drop out starts before a kid walks through the door. One of the biggest focuses for me is early childhood education,” said Mitchell. “One of the things that I like to look at is the total system approach. One person talks about early childhood education and another talks about the perils of kids dropping out. What you think about really is a child’s life, when you talk about the whole system approach, we’ve got to figure what to do with kids when they are not in school. And the reason for dropouts is not just what happens in school, there are a number of things that happen after school that contribute to the dropout rate.”

Another major impediment to black males graduating at higher rates is what happens after the final school bell rings. Mitchell understands how easily black males and others are seduced by the temptations that reach out from the streets like poisoned tentacles, particularly the dead time between the end of school and when parents normally come home from work.

“When I think about my experience of growing up here in Atlanta, when I got out of elementary school, I literally had three hours where I had nothing to do. But what saved me is that my mom was a school teacher in the APS system and my dad was a police officer,” he said. “But I had recreation centers to go to. So, during that three-hour period, I had something that was engaging me while my parents were still working. But I had friends who didn’t have that same level of engagement in Atlanta who really found themselves in harm’s way.”

In order to retain kids in the educational pipeline, some of Mitchell’s colleagues suggested technical and vocational education advocacy. For example, at Atlanta Technical College, the school places 98 percent of its graduates. “So, to me, as Malcolm X once said, ‘education is the passport to our future,’ ” Mitchell said.

“If we’re going to include the educational outcomes of our young people, we have to build partnerships — partnerships that go well beyond the schoolhouse,” he said.