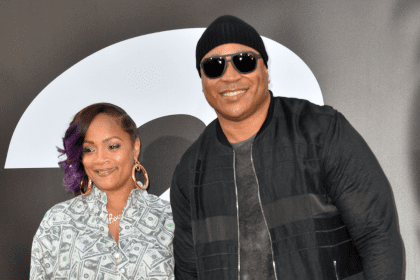

LL Cool J is one of my favorite rappers. The man has always been able to rhyme. He’s always had an under-appreciated versatility. He always knew how to craft great records. Even after he started sleepwalking through albums. Even after the extended foray into sappy duets with the likes of J. Lo. Even after “Accidental Racist.” LL is still one of the all-timers in my Big Book of Hip-Hop Legends.

James Todd Smith had been writing rhymes for years in Queens before he gained any exposure. Rapping around St. Albans, he started making demos in his basement and was beginning to gain attention. Leading up to Radio, the 16 year old had been bubbling for a year on the strength of the underground hit “I Need A Beat,” an ode to writing rhymes that was produced by Mike D of the Beastie Boys, who’d helped him land his deal with the fledgling record label, Def Jam Recordings. After performing the tune at Manhattan City High School, the youngster knew that hip-hop was going to be his career. Columbia signed Def Jam to a distribution deal in 1985, and LL immediately began work on his first album.

On November 18th, 1985, the world got it’s first real taste of who LL Cool J was going to be as an artist. Radio is a propulsive blast of mid-80s b-boy swagger. The songs make little-to-no pop concessions, the productions are brazenly minimal. The album is the first LP produced by the legendary Rick Rubin (with additional work from DJ Jazzy Jay) and the infamous “reduced by Rick Rubin” credit on the back cover is still an apt description of the album’s sound. Radio built on the innovations introduced by Larry Smith on Whodini’s Escape and especially Run-D.M.C.’s self-titled debut. But Rubin’s concoctions were even less concerned with R&B or pop radio tastes; there are no catchy synth hooks like Whodini’s “Five Minutes of Funk” or hard rock riffs in the vein of Run-D.M.C.’s “Rock Box.” This is about as unapologetic as hip-hop had ever sounded up to that point and cemented rap as a genre with it’s own sonic trademarks that didn’t have to appease outsiders for legitimacy. If you don’t like beats, cuts and rhymes, then don’t listen.

Radio outlines the approach that would come to define LL for the next 30 years. The album establishes his loverman persona on tracks like the first official single “I Can Give You More” and “I Want You,” while making sure everyone knows he takes no prisoners on the microphone on cuts like “Dangerous” and the classic “Rock the Bells.” And “I Can’t Live Without My Radio” became an unofficial anthem for young kids in urban centers who walked down the block with their boombox on one shoulder, an ode to the ghettoblaster that had become the symbol of mid-1980s hip-hop. The album stands as a high-water mark for rap’s “boom bap” mid-80s period; the years following Run-D.M.C.’s breakthrough but preceding the emergence of more sample-heavy acts like Eric B. and Rakim. LL was at the vanguard of a movement that included Run-D.M.C., the Beastie Boys, Schoolly D and early Boogie Down Productions; the first wave of “hardcore” hip-hop artists, armed with truck-rattling productions and aggressive rhymes. The beats on Radio took absolutely no prisoners.

But the centerpiece of the album is obviously the teenage LL Cool J himself. He’s as cocky as he would be for the remainder of his career, and it may be hard to fathom just how much of a sensation he was–even at this early juncture in his career. His youth and image–the trademark Kangols and his ever-present ghettoblaster–made him the perfect poster boy for hip-hop’s new generation. On the epic “Rock the Bells,” he announces himself in already-legendary fashion: “LL Cool J is hard as hell. Battle anybody, I don’t care who you tell.” His confidence famously rubbed elders the wrong way, everyone from Kool Moe Dee to MC Shan would try unsuccessfully to take him down a peg in the following years. And his success made him Def Jam’s first and longest-running star. Run-D.M.C. were affiliated with Def Jam via Russell Simmons, but were never actually signed to the label. The Beastie Boys would eclipse Radio in crossover appeal a year after it’s release, but it was LL who gave the label it’s first big push and the clout to take it’s first steps towards becoming the powerhouse brand it would be by the late 80s.

Radio would eventually achieve platinum sales, becoming the first hip-hop album to do so without a music video. He’d missed a video shoot for “I Can’t Live Without My Radio,” much to the chagrin of Def Jam’s Russell Simmons, who “punished” Cool J by making him an extra in the classic hip-hop flick Krush Groove. The film fictionalizes the rise of Def Jam and LL gets a memorable showcase in one classic scene where he briefly auditions by performing “I Can’t Live Without My Radio” for Rubin, Jekyll and Hyde and Run-D.M.C. Two years later, LL would return with Bigger and Deffer, an album that featured a more sample-heavy sound indicative of where hip-hop was heading in 1987. LL never again made an album this anti-pop again and Rick Rubin never produced another hip-hop album that was this stripped down. In that respect, Radio stands as a benchmark of an era in 80s hip-hop when the genre was becoming more and more mainstream but was still eager to operate on it’s own terms and thumb it’s nose at the musical establishment. In the same year that Run-D.M.C. tore through a mock Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in the “King of Rock” video, LL declared that “This ain’t the glory days with Bruce Springsteen–I’m not a virgin, so I know I’ll make Madonna scream. You hated Michael and Prince all the way ever since–if their beats were made of meat, it would have to be mince,” on “Rock the Bells.”

Nowadays, LL Cool J isn’t just a hip-hop elder statesman, he’s a pop culture icon. Grandmas and babies love Cool James now, and it’s interesting to see how his stardom has never waned and yet his music feels oddly under-celebrated. His classic fourth album, Mama Said Knock You Out, turned 25 two months ago. It was arguably the first HUGE rap album of the 1990s and spawned several hit singles that most fans can still recite today; but it’s anniversary came and went with a whimper. Here’s a guy who was as big in 1995 as he was in 1985 and yet so many fans have to be reminded that LL Cool J is one of the best to ever do it. Contemporaries with much shorter shelf lives seem to be more readily acknowledged as legendary emcees. Even with the commercially-successful but artistically empty music he began releasing in the early 2000s, LL’s track record never has been called into question. But his greatness somehow gets disregarded. Maybe it was the way he announced himself as the “Greatest Of All Time” in the late 90s right after the deaths of Tupac Shakur and the Notorious B.I.G. Maybe it’s the way he phoned in the next ten years of his career. Maybe it’s because a generation of young hip-hop fans know him best as an actor who used to rap. Whatever the reason, we seem to have forgotten about LL Cool J. That’s a shame, because one listen to Radio transports you to a time when he was young and exciting and reminds you of an era when hip-hop was less flossy and more fury. James Todd Smith was the face of hip-hop’s ambition and he became a symbol of it’s resilience. 30 years later, we should all thank him for years of great music.

Nobody this good should ever be taken for granted.