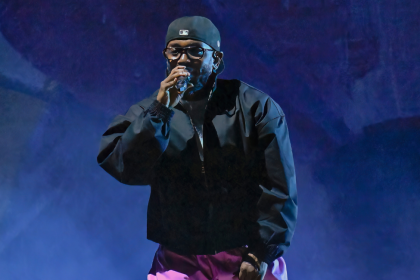

With shackles around his ankles and wrists, dressed in a blue prison uniform, and chained to four other men, Kendrick Lamar approached the microphone at the 58th Grammy Awards with sweat dripping from his forehead and a look of distress. He then began to rap the first verse of “Blacker the Berry.”

“I’m African American, I’m African/I’m Black as the moon, heritage of a small village/Pardon my residence/Came from the bottom of mankind …You hate me don’t you?/You hate my people, your plan is to terminate my culture/You’re evil.” Lamar rapped with fury.

It soon became evident that Lamar’s performance was more than a tribute to Blackness. He was forcing viewers to experience the ugliness of racism.

One week prior to Lamar’s performance at the Grammy Awards, Beyoncé created an uproar with her Super Bowl performance of “Formation.” With dancers dressed in all-black outfits, “Formation” was an ode to the Black Panthers and allowed Beyoncé to embrace being a strong Black woman. But while some conservatives were offended by Beyoncé at the Super Bowl, the performance was merely a tribute to Black culture. Lamar’s performance, on the other hand, was a study of racism and its harmful effects.

Shackles and chains have always served as a vivid reminder of Black oppression. From the slave ships to current day issues of mass incarceration, chains represent how the basic rights of freedom can be a fleeting reality for Blacks in America. Viewers who witnessed Lamar rapping while chained to other Black men got a glimpse of this national problem. Black males from the ages of 25-44 represent the largest segment of incarcerated persons in America, according to the U.S. Department of Justice. Lamar goes one step further by suggesting the root cause of such high incarceration rates.

“You sabotage my community/makin’ a killin’/You made me a killer, emancipation of a real hitter,” Lamar rapped.

Since the abolition of slavery, Black communities have been under siege. The bombing of Black Wall Street in Tulsa, Oklahoma in 1921; the redlining of Chicago and other discriminatory policies in real estate; the influx of crack cocaine and guns into Black communities in the 1980s; and the gentrification of historically Black neighborhoods in Brooklyn, New York, and Oakland, California. The economic and physical pillage of the Black community continues.

Before segueing into his hit song, “Alright,” Lamar broke from the shackles and yelled, “Trap our bodies, but [you] can’t lock our minds!”

Surrounded by African drummers and dancers, the performance of “Alright” began as a celebration for surviving the tribulations of the past and present. But the moment only intensified as a bonfire behind him grew.

Lamar’s performance eventually transformed into a one-man stage show as he paid homage to the tragic killing of Trayvon Martin, which occurred on Feb. 26, 2012.

“On Feb. 26, I lost my life too. That was me yelling for help when he drowned in his blood/why didn’t he defend himself? Why couldn’t he throw a punch?/ And for a community, do you know what this does?/ Add to a trail of hatred, 2012 was taken from the world to see, set us back another 400 years/this is modern-day slavery,” Lamar rapped.

Lamar’s performance ended with a silhouette of a map of Africa with the word Compton inside. It was bold. It was unapologetically Black. It was needed for the times.

But more importantly, for a brief moment, it forced the nation to experience the brutal effects of racism on Black Americans.

Lamar won five Grammy Awards including Best Rap Album (for “To Pimp a Butterfly”), Best Rap Performance, Best Rap Song (both for “Alright”) and Best Rap/ Sung Collaboration (“These Walls”).

Watch performance HERE