On September 7, 2016, the Louisiana Supreme Court will hear the capital appeal of 25-year-old Rodricus Crawford. I spent three months investigating his case, interviewing 10 people, including the district attorney and Crawford’s appellate attorney, as well as reading all of the appellate briefs and expert affidavits. I concluded Crawford was railroaded. At every turn he was presumed guilty and ultimately convicted of the death of his 1-year-old son who medical experts say died of pneumonia. This is one in a series of articles examining how easy it is for a Black man to end up on death row.

Shreveport, Louisiana residents literally begged James Stewart to run for Caddo Parish district attorney. Last year, a coalition of supporters ran ads in the newspaper and on billboards imploring him to run. “This was a calling,” the former Caddo Parish judge told me.

At the time, the area was under scrutiny due to its racist criminal justice system. At least as recently as last year, a portrait of Confederate general and Ku Klux Klan leader Nathan Bedford Forrest hung in a district attorney’s office. Currently, the DA’s office is being sued for discriminating against Black people during jury selection. The office has repeatedly been admonished for the disproportionate number of Black men receiving the death penalty (and the unconscionable number who, like Glenn Ford, are later found to be innocent).

Having spent nearly all his career working within Caddo Parish’s criminal justice system, first as a prosecutor then a judge, Stewart must be aware of Caddo’s history. Yet, during the hour we spoke, he never addressed it. This was as close as he came:

“One problem we have in society now is we try to hide our issues and our problems. It’s just like when someone comes to your house and you take everything and put it in your closet and close the door. They don’t see your problems. That’s why jails and prisons are put away. People put their problems away, nobody sees them, and it’s easier for them to deal with. But unfortunately, our closet is getting full, and so it is starting to spill back out.”

Soon after his historic election as the first Black district attorney, Stewart began making changes. He accepted the resignation of Dale Cox, who was characterized in national media as “Darth Vader” for his “revenge killings.” Cox was responsible for a third of the death penalty convictions in Louisiana.

With Cox gone, another 10 attorneys submitted their resignations, retired or were fired. Stewart replaced them with more women and African Americans, who, in addition to being qualified, resembled half of the parish’s population.

But Stewart has a blind spot: the death penalty. In spite of inherent problems with local capital cases being noted as biased, and often overturned, Stewart expressed his support of the death penalty while campaigning. For all the national attention and scrutiny the death penalty has received, not a single Black civic leader, minister, or community activist is on record questioning Stewart’s support of it.

Soon after taking office, Stewart announced he would seek the death penalty for Grover Cannon, a Black man accused of killing police officer Thomas LaValley. In January, Stewart told the Shreveport Times he was in the process of evaluating all death penalty cases and was “going to start making decisions one case at a time.”

Stewart decided in Crawford’s case to keep digging his grave. His office submitted an opposition brief that urged the appeals court to uphold Crawford’s verdict and death sentence in spite of overwhelming medical evidence that baby Roderius Lott died from pneumonia.

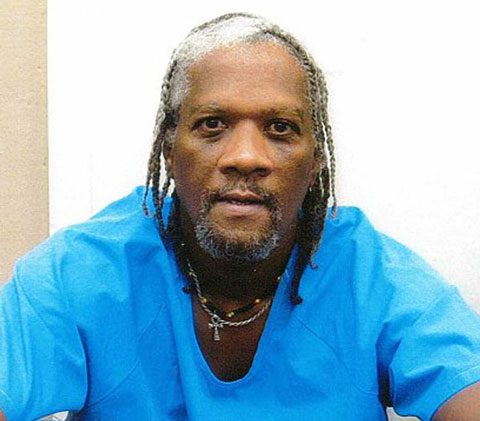

That a White prosecutor widely viewed as racist would need only know that Crawford was an unemployed pothead to surmise he was also a murderer is unsurprising. To understand why a Black prosecutor would perpetuate such a notion, one must understand respectability politics. It reigns in the region’s Black community, and the Stewart family is part of its royalty. Not only because they are judges — Stewart was first sworn in by his niece, Caddo District Court Judge Karelia Stewart, and at his official ceremony, by his brother, Carl, currently Chief Judge for the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Judicial Circuit — but also because they are dignified, hardworking, and regular churchgoers. Crawford is none of those things, so instead of the Black community coming to his rescue, his life raft is a White appellate attorney named Cecelia Kappel. Click here for her story.

More in this series:

Why does this town keep putting innocent black men on death row? (video)

Rodricus Crawford’s timeline to die

White defender, Cecelia Kappel mounts defense, faces Black D.A.