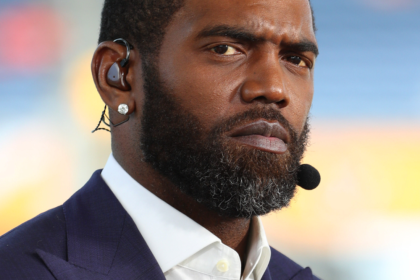

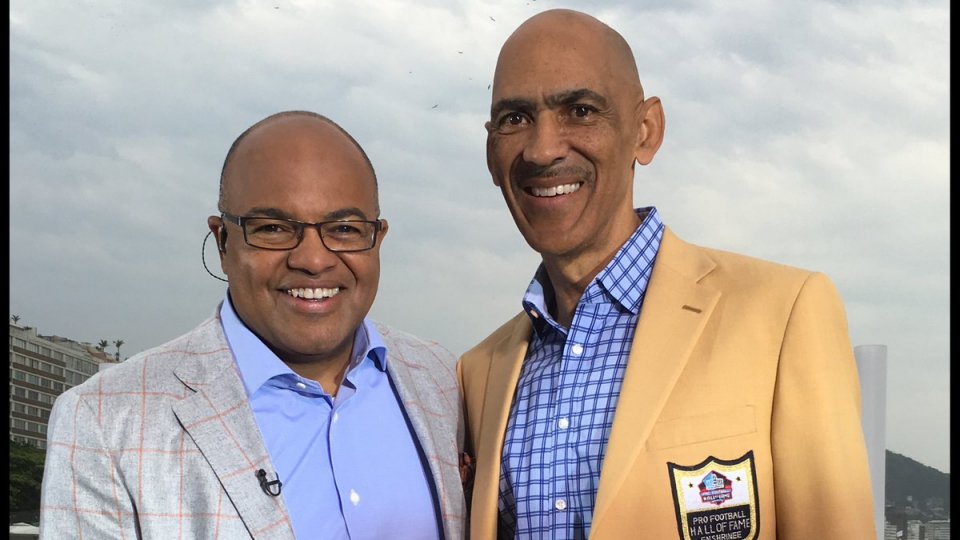

Mike Tirico, the longtime ESPN broadcaster, and now NBC Sports announcer, has trouble saying he is Black. He claims he’s just an Italian kid who grew up in the Queens borough of New York City, who people keep insisting is Black.

In a recent sit-down with the New York Times titled, “Mike Tirico Would Like to Talk About Anything but Mike Tirico,” the sportscaster had this to say about race:

“Why do I have to check any box?” he said. “If we live in a world where we’re not supposed to judge, why should anyone care about identifying?”

He adds, “The race question in America is one that probably never produces a satisfactory answer for those who are asking the questions.”

There’s little wonder, with his mindset, why he and Tiger Woods got along so well. Both suffered some level of mental anguish over Black identification. When he first entered the PGA Tour in the 1990s, Woods reportedly called himself a “Cablinasian,” a combination of Caucasian, Black and Asian, and it was very apparent that he, too, felt shame about the Black part of himself.

The conversation with the Times about race stemmed from a 1991 piece from the Post-Standard, via Bar Tool Sports, in which Tirico claimed that he’s not sure he’s Black:

“When people go around and say, ‘You are black’—well, I don’t encourage it, but by the same token I don’t back off of it,” he says. “If you want to call me that, that’s fine. But, you know, in my whole family, there’s nobody I know who is Black.”

Michael Todd Tirico grew up in a middle-class Italian family in Queens, about a five-minute drive from Shea Stadium. Tirico’s parents, Donald and Maria, were separated when he was about 4, and he says he has since lost contact with his father’s side of the family. Tirico is an only child. Because of his dark skin and ethnic features, Tirico says, most people assume he is Black. But he’s seen pictures of his father, his father’s mother and his father’s sister, all of whom are white, Tirico says.

“The only contact I had growing up was with my mom’s side of the family. And they are all as white as the refrigerator I’m standing in front of right now,” Tirico says, standing in his kitchen in the Clay townhouse where he lives.

Someday, he says, he wants to do genealogical research to find out if he has a Black ancestor, but it’s not something he considers a pressing issue. Tirico concedes, though, that his uncertain ethnicity sometimes makes others uncomfortable.

“I know the story sounds like a lot of bull, but it’s the truth” he says. “Does it matter to me? Yeah, I’d like to find out the truth at some point, so I can answer questions for my kids. But me? I’m living, I’m working, I’m leading an upstanding life. I don’t worry about it.”