Hip-hop holiday signals a turning point in education for a music form that began at a back-to-school party in the Bronx

This article written by : A.D. Carson

Assistant Professor of Hip-Hop, University of Virginia

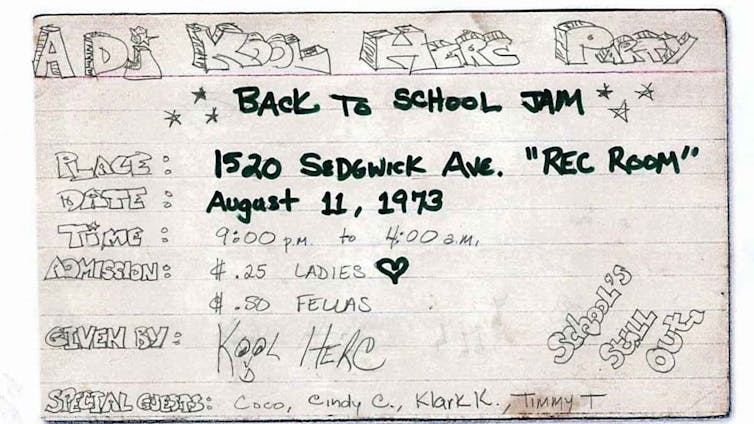

Whenever I teach courses on hip-hop at the University of Virginia, I provide a brief overview of where hip-hop music began. One of the important dates I use is Aug. 11, 1973. That’s when DJ Kool Herc, who was 18 at the time, threw a “Back To School Jam” for his sister Cindy in the South Bronx – in the rec room at 1520 Sedgwick Ave., to be specific.

The landmark back-to-school party thrown by the Jamaican-American DJ, whose given name is Clive Campbell, will be officially and rightly recognized on Aug. 11, 2021, as Hip-Hop Celebration Day, as designated by Congress. August 2021 has also been designated as Hip-Hop Recognition Month, and November 2021 will be recognized as Hip-Hop History Month.

The hip-hop holiday, if you will, represents yet another milestone for hip-hop as its stature and prominence as a literary art and musical form continue to grow.

Multiple origins

Of course, the true genealogy of hip-hop is far more varied and complex than a single back-to-school party in the Bronx.

In his introduction to the “Yale Anthology of Rap,” historian Henry Louis Gates Jr. writes that the first person he heard “rap” was his father, who was born in 1913, as he was “signifying,” or playing “the Dozens,” a pastime in which participants trade searing insults about one another’s relatives, typically their mothers, as a way to teach mental strength.

In the 1968 memoir of Black Panther leader Eldridge Cleaver, “Soul On Ice,” Cleaver – in an entry dated Aug. 16, 1965 – describes a type of rap he heard in the wake of the Watts uprising, a six-day-long rebellion in the predominantly Black neighborhood in Los Angeles sparked by a violent exchange between police and bystanders when a young Black motorist was stopped and arrested by a member of the California Highway Patrol.

He refers to young men he calls “low riders” assembled in a circle on the basketball court after leaving the mess hall in Folsom State Prison that previous Sunday morning. The Watts uprising had been going on for four days by then. The men “were wearing jubilant, triumphant smiles, animated by a vicarious spirit.” A round of signifying hand gestures turned to speech after one asked, “What they doing out there? Break it down for me, Baby.”

Cleaver writes that one of the low riders stepped into the middle of the circle and began to speak:

“They walking in fours and kicking in doors / dropping Reds and busting heads / drinking wine and committing crime / shooting and looting / high-siding and low-riding / setting fires and slashing tires / turning over cars and burning down bars / making Parker mad and making me glad / putting an end to that ‘go slow’ crap and putting sweet Watts on the map / my black ass is in Folsom this morning but my black heart is in Watts!”

Cleaver describes the laugh shared by the men in the cipher – or small, circular gathering – as “cleansing, revolutionary,” as “tears of joy were rolling from (the speaker’s) eyes.”

California rapper Ras Kass named his debut album, released in 1996, after Cleaver’s book.

Kool Herc, the pioneer

Herc is described in the Yale anthology as “the man most often mentioned as the sonic originator of hip-hop.” He invented “the break” by using two turntables – and two copies of the same album – to extend a song’s instrumental, typically highly percussive, portion. He then took the signifying that Gates and Cleaver describe and performed a version of it over the separated song breaks he blasted on his sound system. His breaks and banter bade dancers to improvise to the music he played. Tricia Rose, author of pioneering hip-hop scholarship including “Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America” writes that “DJ Kool Herc was a graffiti writer and dancer first before he began playing records.”

Though modern graffiti writing is said to have originated in the 1960s when a 12-year-old Philadelphia kid named Darryl McCray began tagging his nickname, “Cornbread,” on the Philadelphia Youth Development Center walls, and then eventually all around the city, DJ Kool Herc embodied all of the original elements of hip-hop: DJing, emceeing, break dancing, and graffiti writing.

Worldwide phenomenon

In the years since that back-to-school party, hip-hop has become a well-recognized global phenomenon. It is one of the most widely consumed musical forms worldwide. It is also a widely sampled and highly scrutinized cultural movement.

Since hip-hop began as a back-to-school party, it follows that it should be taught in the halls of academia. College classes as far back as the 1980s have taken up hip-hop culture and artists as the objects and subjects of study.

In 2013, the Hiphop Archive and the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute at Harvard University established the Nasir Jones Hiphop Fellowship. The fellowship – named after the rapper Nas – is meant for select scholars and artists with “exceptional capacity for productive scholarship and exceptional creative ability in the arts, in connection with Hiphop.”

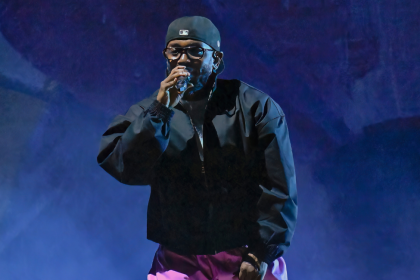

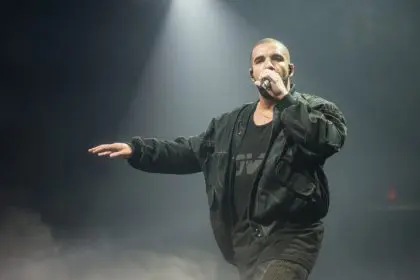

Kendrick Lamar’s “DAMN.” received the 2018 Pulitzer Prize for music. In 2019, New Orleans rapper Mia X joined the music industry faculty at Loyola University. She is one of many rappers and producers to teach at a university. Black Thought from the widely acclaimed rap band The Roots will be hosting a residency at the Kennedy Center in October 2021 during which he will talk with contemporaries about art, inspiration and creative consciousness.

[You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can get our highlights each weekend.]

A hip-hop dissertation

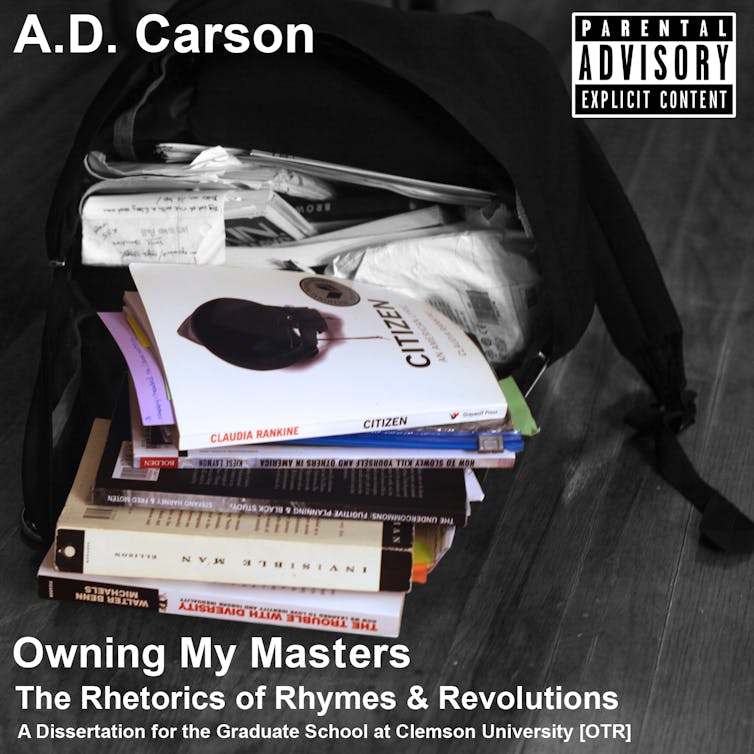

My own forays into academia are squarely rooted in hip-hop. I accepted my current job – assistant professor of hip-hop – after I submitted my doctoral dissertation as a rap album and digital archive in 2017.

I had few academic models for my work to follow — those laid out by Gates’ father, people like the low riders from Cleaver’s memoir, scholars like Tricia Rose and pioneers like DJ Kool Herc. I wanted my work, in rap form, to be the scholarship on its own. Hip-hop has always been academic to me, even though it often seems as though making music, DJing, break dancing or doing graffiti painting as scholarship are usually acceptable only outside of formal spaces of learning, as part of an alternative curriculum.

Congress’ formal establishment of a hip-hop holiday and month of recognition – at least in 2021 – lends credence to the notion that hip-hop finally deserves a place in academia as a discipline of its own. From my perspective, it is long overdue that hip-hop be seen not solely as a subject of study but as a tool to continue to produce new knowledge and new ways of presenting it.

Hip-hop’s influence on other disciplines is as abundant as its influence on other music and art forms. Perhaps soon, in celebration of Cindy and Clive Campbell’s historic “Back To School Jam,” some students will be going back to school to become fully immersed in the academic rigors of the culture being celebrated nationally on Aug. 11.![]()

A.D. Carson, Assistant Professor of Hip-Hop, University of Virginia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.