This is not a tell-all as much as it is a cautionary tale.

Detroit is a home for everyone, but it is a place identified the world throughout for Black culture. It is the cradle of Motown, which shaped Black American music and style, and the place where Black home ownership and entrepreneurship reigned from the mid 20th century. In recent years, Detroiters are watching the erosion of Black presence and power in the city. For a multitude of reasons, many arguably by design, we have seen a regression in home ownership and watched and experienced the decline of the Black middle-class. Suburbanites, well-funded transplants, and corporations are claiming large swaths of local real estate, dominating downtown Detroit, and changing the complexion of many Detroit neighborhoods. Many of us can no longer afford to live and play here.

These are not complaints, but plain realities and indisputable observations. Wealth and opportunity gaps are widening throughout the country, the world even. Urban areas are under siege and black and brown people everywhere are struggling to hold onto a sense of place.

With that in mind, Valerie Irwin and her niece, Misha McGlown, saw an opportunity to create a place for creatives and Black Detroit on the city’s historic West Grand Boulevard. They committed their time and personal resources – blood, sweat, tears and endless dollars – to developing Irwin House Gallery, which is becoming known for incubating talent and for their open and generous partnerships with other local organizations and entrepreneurs in the production of creative and community-centered projects and programs. Misha brings with her a wealth of knowledge and business acumen from a decade+ long curatorial and arts administrative career in New York City. Additionally, her experience as an award-winning fine artist gives her a unique connection to the artists she serves. And, Mrs. Irwin provides the back-end executive strength along with all the warmth of family.

The fact that Irwin House is a resource for the greater arts community is evident in the extensive and diverse crop of talent the gallery has worked with since first opening their doors in 2018 for an Aretha Franklin tribute exhibition, while the building was still in the throes of rehab. But, at the core of their work, Misha and Valerie are independent Black women business owners, realizing a vision, struggling to maintain a not-for-profit, and fighting to save a spot on Detroit’s most historic Boulevard for minority voices and creativity in a changing landscape that rarely flings its doors open for us.

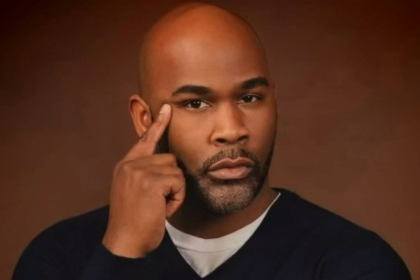

In the Fall of 2020, as the initial horror of the COVID-19 shutdown began to ease, a local artist, Jonathan Harris, approached Irwin House Gallery about presenting an exhibition of his art along with three of his friends. Misha had met Harris the previous year at the Detroit Fine Arts Breakfast Club, purchased a painting and invited him to participate in their sophomore exhibit, DETROIT FUTURE HISTORY, in the Fall

of 2019. Harris had never presented or installed an exhibition before and expressed that he was driven to the task as a result of having been rejected numerous times as an emerging artist. With the uncertainty of COVID at hand, Misha had not yet begun to populate the gallery’s schedule, so his timing was perfect and the answer was, without question, “Yes!”

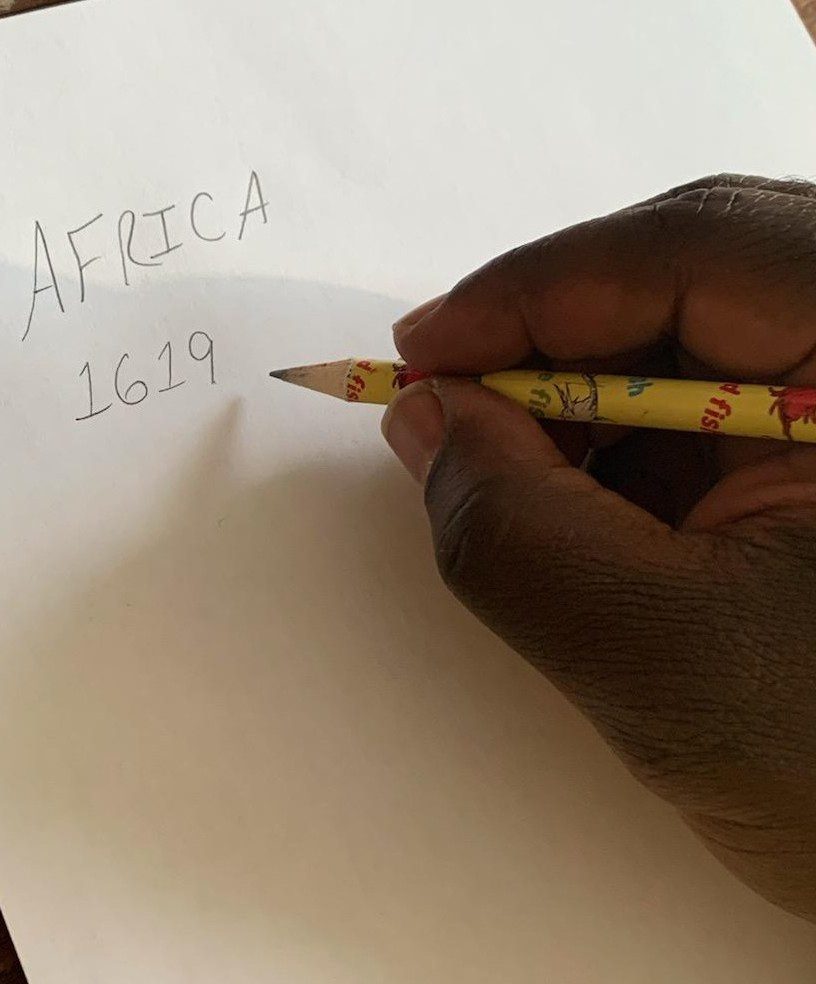

That was the start of a working relationship and friendship between artist Jonathan Harris and Irwin House Gallery director, Misha McGlown: One that was centered on his development as an artist, supporting his projects, providing professional and artistic advice, writing and developing his promotional materials, housing the artist for ten months at zero to subsidized rent and providing unlimited access to spaces for him to create, self-promote, do business and socialize for almost two years. All of this culminated in the whirlwind success of his Critical Race Theory painting at the end of 2021 – which was painted, exhibited and ultimately sold on Irwin House property, and brought to the attention of the press via Misha’s focused writing and extensive outreach.

Following the viral success of Critical Race Theory – a painting depicting the erasure of Black history –Misha’s full attention was diverted to helping Harris manage his newfound fame for a period of nearly three months, uninterrupted. Harris became the gallery’s number one priority and Misha’s dawn-to-midnight commitment included fielding a barrage of calls, emails, appointments and press appearances, vetting requests, writing and submitting paperwork, scheduling and prepping the artist for appearances (which were primarily staged at the gallery), editing his images for publication, and even developing a web site for Harris, literally, overnight. None of this was compensated and, despite being presented with extremely modest invoices for services, the artist has to date expressed and demonstrated a refusal to pay for the heap of services he needed, requested, accepted, and received.

Meanwhile, Harris set up a successful operation for packing and shipping Critical Race Theory prints in response to the sold original’s viral success. The gallery supported him in his initial print run and continued to direct inquirers to his site to make print purchases. Harris first ran the print packaging operation out of the gallery then, in a possible attempt to recuse himself of any financial obligation, moved his operation to the family’s other property, just two doors down, where he was living and working – again on subsidized terms and still using the gallery’s resources and support. Harris refused to sign an Agreement presented by the Irwin House, asking for a mere 5% of prints sold, while selling thousands of prints to consumers all over the world and excluding the gallery – a non-profit that thrives solely on commissions and donations in order serve artists and community – from any part of the process or its rewards.

The gallery dropped the percentage down to 2.5% in a subsequent invoice, and he still refuses to pay.

Guests often ask to see a Critical Race Theory print when they visit Irwin House Gallery. They don’t have one. The framed artist proof that hung for a time in its foyer, presumably a gift, was retracted by the artist before he vacated the premises on April 30th. In that same month, Harris told Downtown, a Birmingham/Bloomfield publication, that he had sold over 5,000 prints internationally, at $100, $150 and $200 per unit. He has expressed and holds firm that not one dime of this is owed to the gallery.

Although, it had been widely communicated throughout the press and understood between Harris and Irwin House Gallery that the follow up to Critical Race Theory success would culminate in a solo exhibition of his anticipated new work at Irwin House Gallery, the artist, in a clandestine move, is set to take his fame, his cache and his 40k social media followers (garnered from CRT success) to a downtown gallery that stands to benefit fully from the work and investment sunk into Harris by two independent and underfunded Black women on The Boulevard. Not unlike the CRT painting, this new body of work (now slated for sale elsewhere) was created entirely on Irwin House property up until his departure. His subjects and source materials were photographed at the gallery, videos were created there and dozens of interviews including CRT and this new body of work were also staged at Irwin House Gallery and on its grounds. Yet, now that there is an increased value for Jonathan Harris art because of all of this – further bolstered by Misha’s push to have him inserted into a recent exhibition at prestigious CHRISTIE’S in New York – and a real opportunity to support community, he has acted on a choice to remove his profits not only from the black community, but from the organization and the people, the women, that invested in him and sustained and nurtured him, personally and professionally, when no one else would and at their own expense.

But, this is not purely about white and black. Of course, Irwin House Gallery stresses and demonstrates that artists and galleries of any ethnicity can and should work together on the merits of their talents and relationships built.

This is cautionary for any of us who claim to love and support our black community and businesses to make those claims not only in word, but in deed. For an artist who has built his reputation and immense following upon telling black stories and reportedly loving and promoting black culture, it is ironic, abysmal even, that he would leap at the first opportunity to funnel his fortune outward, with no sense of obligation or gratitude to the Black organization that led him in crafting success and, moreover, proved beyond capable of managing and advancing his immediate steps forward. Perhaps some of his actions speak to an insecurity in his own blackness, stereotype threat, or a deep-seated belief that validation can only be achieved through white recognition and representation. These are post-traumatic slave mentalities we can all stand to check ourselves for – no matter how conscious or “woke” we believe ourselves to be.

As a professional team, Misha and Jonathan had been, in fact, a tour de force. But, by Misha’s own admission, there had been harsh verbal exchanges due to a laundry list of grievances over time, and the idea of a sustainable long-term relationship between the artist and gallery became improbable. But the dates that he requested for his show were held exclusively for Harris – never rebooked or given to another artist – amidst (what was believed to be) a continuing conversation on the subject and in honor of a longstanding and very public commitment to host a post-CRT exhibition as a follow up to the light he and the gallery had created and shared mutually.

As Black Americans who are facing displacement all over the country and whose businesses, by-and-large, will not survive without the concerted patronage of one another, how many of us are just giving lip service to supporting our own culture, and how many of us are willing to truly put our dollars where our mouths are? In a time when the world is recognizing Juneteenth, and the humanitarian and economic injustices inflicted upon us by others, will we continue to do this to ourselves? Will we continue to hurt each other, financially?

Brought to international renown for his visual and verbal expression of love for Black people, Harris has been quick to point out when others in the art community are appropriating black culture for material gain. It is possible to exploit your own culture for the same.

This is a sad day on the Detroit art scene and a costly lesson learned for an emergent west-side business. The gallerist would only comment that she would “protect herself and her family more carefully, moving forward.” But, the lesson here is much bigger than a single soured relationship between an artist and a gallery: Supporting Black spaces is tantamount – in Detroit and everywhere – if we wish to compete, remain relevant, prosper, and be collectively seen and heard in these aggressively-changing landscapes and in the face of widespread displacement and diminishing democracy. Despite the declaration of new holidays, black livelihood has never been more vulnerable. The hope is that we will all work harder to protect Black spaces and aim to be more intentional about the way our dollars and cultural currency flow through, in, and outside of our communities.

Author: E.L. Francis