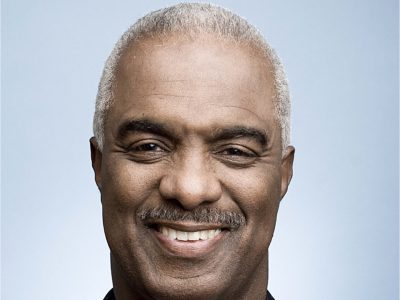

In 2014, as Ferguson, Mo., erupted in protests following the shooting death of an unarmed Black teenager, Wole Coaxum, an Oxford-educated African American financial executive, sat in his office at a Fortune 100 company and considered ways to close the economic gap.

Two years later, he launched Mobility Capital Finance, Inc., or MoCaFi, as a digital banking platform that would target the more than 50 million unbanked and underbanked people living in the country.

By 2020, the platform had enrolled more than 25,000 users, raised millions in seed rounds, and partnered with major multinational companies in addition to several cities and municipalities. That same year, as MoCaFi unveiled an upgraded platform, Coaxum was featured in the New York Times business section as “Trying to Correct Banking’s Racial Imbalance.”

Before starting MoCaFi in 2016, Coaxum served as Managing Director at JPMorgan Chase, where he held a series of leadership positions in Business Banking, Card Services, and Treasury & Securities Services. Before joining JPMorgan in 2007, Coaxum was a senior executive of Willis Towers Watson. He served as Chief Financial Officer & Chief Operating Officer of Willis North America and Chief Executive Officer of Willis Canada. He started his career at Citigroup, working in investment banking, asset management, insurance, and corporate functions. Coaxum has been recognized for his consistent track record of developing and implementing a broad array of high-impact and strategic initiatives which achieve measurable results.

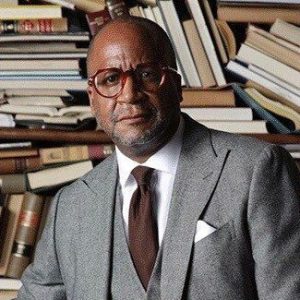

Munson Steed: Hey, everybody! This is Munson Steed, and we are on “CEO to CEO.” I’ve got one of the biggest and best CEOs to share insight on finance and a vision for you. Wole Coaxum is here with me today, and I am so proud of him. He wants to make sure that we have that opportunity, and he didn’t have to. But he did. Can you share your journey to becoming CEO of this phenomenal company, share the name and the vision that you have today for us?

Wole Coaxum: I’d be delighted to, Munson. But first, I want to thank you and all that you’re doing to bring to light the work of all of us who are trying to make a difference with our companies. Your ability to share our stories makes us stronger and makes the community that you serve stronger. So thank you for that, and keep up the great work.

MS: Thank you.

WC: As it relates to MoCaFi. So, I had the great pleasure of working in several well-known financial institutions. I spent time at Citigroup. I spent time at Willis. I was the Chief Operating Officer at Willis, and I know you’re in Chicago, so that means something to you. And then, I was also the Managing Director at J.P. Morgan. There, I was one of the most senior people and had a chance to run the sales and relationship management for their global commercial card business as a sales leader in the Treasury Services business, focusing nationally on companies that were $2 billion in revenue and then the large ones like Walmart and whatnot.

Finally, I was the No. 2 guy in business banking nationally, where I had all the bankers, all the customers—about 2 million customers, and all the branches, which is about 5,600 branches, reporting to me, trying to figure out how to grow those businesses. And then, I had my George Floyd moment after the death of Michael Brown. Where I was sitting, as we all were, reading about what was going on there, watching the images. I was a history major in college. I remember vividly the, and I know Munson you’re familiar with it, the documentary “Eyes on the Prize,” and that captured what was going on in 1968.

What I saw happening in 2014 looked an awful lot like what was going on in 1968. I thought to myself, “How can I use my time and talents and skills to address the hurt that I saw coming out of that Ferguson community?” That hurt in the Ferguson community was a group of people who were looking for us. They had a social justice agenda, but in my mind, it needed an economic justice agenda. If we can bring an economic justice agenda with the social justice agenda, we can move that community forward.

So, I quit and decided to figure out how to influence that economic justice agenda and drive that agenda. I thought about buying a bank. I thought about setting up a fund to invest in startups to address the problem. But this goes to a very important thing for your audience: Which is, I had a mentor who had invested in companies such as SoFi and Lemonade and others, who said, “Wole, I think you should start a company to solve this problem, and I would like to be one of your first investors.”

That gave me the confidence to go out and start MoCaFi to address the economic justice agenda that was inspired by Ferguson. There are just lots of people, Black, Brown, White, and otherwise, who are underserved financially in this country, and we think MoCaFi is a great solution to solve that problem.

MS: Well, thanks for that. But for those who don’t understand how important it is to be banked, what does it stop you? What can’t you do when you don’t have a financial relationship with a bank? When you don’t have someone that says, “Hey, you’re creditworthy over time and have some history.” Why MoCaFi?

WC: If you don’t have a bank account, you find yourself in a situation where you’ve got to pay somebody to get your money. Which seems counterintuitive. I remember we were doing some of our market research. We would spend some time in check cashers, and check cashers, quite frankly, are more prevalent in this country than McDonald’s, Burger King, Wendy’s, and other stores combined. They are such a prevalent part of our economy. We were sitting in one of these check cashers, talking to people, and asking them, “Why do you go here?”

One individual said, “You know, it’s terrible. I’ve got to work 40 hours, bring my check to cash at the check casher because I don’t have a bank account, and I only get paid for 30 hours.” The average Black person who doesn’t have a bank account can spend $40,000 in fees over their lifetime. Just imagine if they didn’t have those fees and were able to save that $40,000. That would significantly close the wealth gap that we have in this country between Black Americans and White Americans.

And so, to operate in cash not only puts you in a situation where it’s more expensive to operate, but it makes you vulnerable. You don’t have a safe place to keep your cash. You put it under your mattress, you put it in a safe at home, and you’re missing out on your money making money because you don’t have the benefit of compounding, which exists when dollars are being invested. There are a lot of challenges and downsides to not being banked. It becomes a challenge to demonstrate that you are a creditworthy individual. You talk about the importance of a credit score.

Credit scores are established based on bill payment behavior, and a credit score, for better or for worse, is something that influences not just how much it costs to borrow money. If you’ve got a better credit score than I do, it’s going to be cheaper for you to borrow money than it is for me. That’s the obvious one. But it also influences things that you might not otherwise be aware of. Insurance companies use credit scores to determine what rate of premium they’re going to charge an individual. Financial institutions look at your credit score to figure out if they’re going to hire you or not because they say if you don’t have a good credit score, that means you’re not managing your money well. Why am I going to trust that you’re going to manage our money as a bank or other people’s money well? That could limit your ability to get that role.

Also, when you’re applying for housing, particularly rentals, obviously in a mortgage, they’re going to look at your credit score. Many rental units look at your credit score before they decide they’re going to rent to you. It has real implications in terms of the ability to access lots of opportunities. So, your final question, why MoCaFi? What we’re trying to accomplish at MoCaFi is to ensure that everyone has access to a low-cost, high-quality banking product. Those of us who have access to the Chases of the world or the Citibanks or the Wells, we take it for granted that we’re going to have access to our money and be able to make deposits for free and get cash out of the ATM for free.

The reason there are ATM fees is because so many individuals have more month than money that the traditional banking model doesn’t work, where if you leave excess balances, the banks can invest those and keep the interest and pay you a little bit in terms of the money that’s been deposited in the account. But if you have money that’s coming in and out and the banks don’t have an opportunity to invest those excess balances to make a little bit of something to cover the cost of offering that checking account, they then turn around and say, “Okay, we’re going to have to charge you overdraft fees, or we’re going to have to charge you ATM fees,” which is part of the reason we get to that $40,000 number we talked about.

MoCaFi is very focused on making sure that people can open up accounts that don’t have monthly minimums. They don’t have fees to open up a big account. We’ve turned stores like 7-Eleven, Walmart, Walgreens, and CVS into bank branches where people can deposit cash into their accounts for free. We have ATMs in those stores that are free, and we also have partnerships with Wells and Citibank, where if you take a MoCaFi card and go to any of those places, you can take money out of the ATM for free.

The final thing we do, we do lots of things. We have check deposits. You can take a picture of your check and have instant access to those funds, so you shouldn’t have to go to a check casher. We also take rent payments and report those to the credit bureaus. I was inspired by that concept a couple of years ago. Experian did an analysis where they went to New York City Housing Authority residents and said, “Hey, what would the impact be on your credit score if we took a rent and made it a part of the credit score?”

What they found is that over 90% of the people, in a study of 2,000-3,000 people, 90% of the participants saw some increase in their credit score—15, 20, 30, 50 points, which is significant. The other thing that they found is that 25% of those individuals who were thin-to-no credit file, where there just wasn’t enough data to figure out what the credit score should be for that individual, 25% of those individuals who started as thin-to-no credit file, once you added rent, became 700 credit score or better. It’s compelling that an individual who goes from a thin-to-no credit score, who is not eligible for certain products, now you add the ability to capture their behavior.

Now we actually see that person’s really a 700, that opens so many doors and changes the game in terms of access to economic opportunities. We want to make that available to all of our members. We think, as MoCaFi, we’re bringing those services to communities where traditional banks have left. 80% of the bank branches in this country that have closed have been in low- and moderate-income communities. You can imagine that a disproportionate number of those bank branch closures have been in Black and Brown neighborhoods.

We provide that banking service, and then we go one step further. We’ve created a program called On Our Block, and On Our Block is our ability to bring place-based solutions to the community. I’ll give you a great example. We were in Cleveland about two or three weeks ago. We brought Malik Yoba and a couple of others. We had some food, some music, and we brought some financial coaches to the community.

We were able to have a community conversation sponsored by KeyBank, and we were able to have a community conversation about what members needed to do in that community in order to prepare themselves for homeownership, in order to prepare themselves for entrepreneurship, how to give them access to our financial coaches, and become aware of the resources that were in the Cleveland community so they can move themselves forward. We’ve been doing that in Birmingham, St. Louis, New York, Los Angeles, and we think that is a compelling way to start to bring a movement to our communities so they can start to create a path towards economic mobility.

MS: But you could be retired and relaxing and not changing the lives of many of those unbanked individuals. As a CEO, what is your vision 10 years from now on where this community has been impacted?

WC: So, there are several areas that we would like to see an impact in 10 years hence. One, we have in our communities a homeownership rate, which is about the same as what it was when President Johnson signed the Fair Housing Act in 1968. Ten years hence, we would like that statistic to be one where we have improved the homeownership rate—10, 15, 20, 30%.

Second, we see large portions of our communities who are coming out of the criminal justice system, who don’t see a pathway to moving themselves forward economically, and we would like to see that number of people going back into prison come down significantly, because they have access to banking products, which is important, as we talked about earlier, component of the ability for people to move forward.

Third, we see a real opportunity to help the government become more efficient. Our business model is one where it’s very expensive from a customer acquisition cost perspective to make a direct-to-consumer marketing play. So, what we figured out was, okay, if we can make a city, county, state, or federal government more efficient in terms of getting resources to the un- and underbanked, we can reduce the cost to that particular city. We can increase the amount of access that individuals have to resources that otherwise weren’t getting to them. Then that gives us an opportunity to provide them with additional services like our bank account and other tools that can help with their economic mobility.

We have the good pleasure now of being in about 20 cities and counties across the country. Ten years hence, we would like to find ourselves in the major cities across the country, working with some of the largest counties in the country and small ones, some states, and working with the federal government to make sure that resources are getting to people. I’ll give you a good example. Mayor Garcetti, when he was the mayor of Los Angeles, said, “I want to create a contactless government. I want a way for residents of Los Angeles to be able to have single sign-on for city services. I want a way for the residents of Los Angeles to be able to receive money electronically from the city. I’d like a way for city residents to be able to pay for city services electronically.”

How do you do that when there are 500,000 people in Los Angeles who do not have bank accounts? And so, we’ve put our infrastructure in place. It’s called the Angeleno Connect Card in the city of Los Angeles. We’re in the process of replicating that as we speak in New York City, and we want to bring that to cities, big and small, all across the country. So that’s the vision 10 years hence of where we’re having an impact and making sure that communities are inclusive, safe, and economically thriving.

MS: Well, I appreciate that. So, if you were giving a speech at a Morehouse, Howard, Fisk, or even a Spelman, and you were going to share the type of CEOs that you would like to see coming out of these organizations in the future, what would the title of your speech be, and what would the three things you would challenge them to do?

WC: That question hits home closely. First, as the husband of a woman who’s got two HBCU degrees—one from Morgan State and one from Howard—and the proud father of a young lady who’s going to Spelman as a freshman in the fall, that question means a lot. In terms of what I would like, the name of the speech is “Social Currency is as Powerful as the Dollar.”

The three ideas that I would build within that conversation would be: One, good ideas attract capital. If you have a good idea and you are able to articulate that idea clearly in terms of the benefit that it will have on the customer, the target audience, and can do it in a way that makes money, that turns $1 into $2 and so on, that’s an investable idea. You’ve got to have that, got to nail that part of it. Being in those institutions, which I believe are more important than ever—we can have a separate conversation on that point—they’re being trained to develop those ideas. That’s point one.

Point two would be, being in those institutions and, as they go throughout their journey of their lives, being able to develop relationships that are meaningful. A meaningful relationship doesn’t mean I talk to you every day, but a meaningful relationship is one where you can find common ground with somebody. You can inspire them or be inspired by them, and you have the ability to help them realize their dreams and potentials, and they can help you realize yours. But it’s not transactional. It’s long-term, how can we help each other? Building those kinds of relationships will be critical to long-term success.

Because I have a simplifying assumption that if you’re at a place like Morehouse, if you’re at a place like Spelman, if you’re at a place like Morgan State, you are equally talented. So, the difference between you moving forward and my moving forward is not going to be driven by talent. It’s going to be driven based on the quality of our relationships and the ability to use those relationships to move an idea forward. That’d be the second idea.

The third idea that I would provide to those young people is a sense of history. They are standing on your shoulders. They’re standing on my shoulders, and you and I are standing on the shoulders of individuals before us who sacrificed a tremendous amount for us to be in the position to do the things that we’re trying to do. Let me give you an example. My great-grandfather was a guy named Anderson Hunt Brown, son of slaves, born in the 1880s in Virginia, got a sixth-grade education, made West Virginia his home, and was able to start a real estate company.

He was a butcher for a little while, he was in a band for a little while, but he ended up going into real estate. His real estate business in a segregated South created opportunities for Black people, not just an opportunity to have housing. He was the president of the Deacon Board of the church, bought land right next to the church, built an office building—two stories, first story retail, second story commercial space. The folks didn’t have any money to start their businesses, he would invest in the barber chair, he would invest in the stove so they could do the cooking or whatever. That was WeWork before anyone even knew what a WeWork was.

But that was a part of the community, and he used his economic platform not just to create the Charleston, W.Va., version of WeWork, but also to integrate the library, to integrate the restaurant at the airport, to integrate the swimming pool. So, when I thought about starting MoCaFi, I was thinking about the work that he did to move his community forward. I thought to myself, “What can I do to move my community forward?” Being a senior person at J.P. Morgan gave me the tools to be able to go out and reimagine how I can move my community forward.

I would leave that as the final sense, the final idea I would leave with those young people, which is they should have a sense of history and build upon those who have come before so we can move our community forward. If we move our community forward, we’re moving all communities forward in this country, which is very exciting.

MS: Lastly, what would you say to those young people who want to be an entrepreneur right now versus the opportunity to go inside a Chase and learn and glean CEO styles that you were able to gain from being at one of the best in the entire business that you’re now in?

WC: There’s no right or wrong path. I often think about it as an inside game versus an outside game. You could suggest that a Chase or a Wells or a Citi are inside games, and you go into those institutions, and you have a chance to see what it looks like for a high-functioning organization that spans several lines of business, that is operating across multiple time zones, and to watch and see how that is built, functions, the processes, procedures, observe the language of the CEO. Remember, as you know, it’s not just Jamie, who I’ve known since 1992.

He has a whole team of lieutenants and up-and-comers who you can learn from, talk to, get mentorship from. So that’s absolutely a very compelling path. That’s my path. When I was there, I had two fundamental truths that I thought a lot about. One, I felt like I was getting paid to learn every day that I was there. I was like, “Wow, they’re paying me to,” and obviously I’m doing my job and delivering, but it’s an opportunity to learn new situations, solve particular problems, understand how risk works with legal, which works with the business unit, and learn from people like Jamie and others. That’s one.

The other thing that I took away from that was the importance of always having a door open to provide mentorship and feedback to people right behind me in those organizations. As a young person, you’re always looking to have a coffee with somebody. I took advantage of that and said, “I gotta pay it backwards, if you will, or pay it forward,” and I would always have my door open. There’s a lot you can learn in those institutions.

Now, some people may say, “You know what? I want to start my entrepreneurial journey now.” That’s terrific. What you have to do is create your own playbook in terms of observing the experiences of others and learning from others. The library, or Amazon, or Audible, wherever you get your information, is a tutorial where you can learn from the lives of others, both living and dead, based on what they’ve written. Those become the mentors that you might not have access to on a day-to-day basis in a real-time way if you’re at a J.P. Morgan or if you’re at a Wells.

But you’ve got to recreate it both from reading and then going and identifying individuals that you admire and reach out to and try to develop a relationship with. You have to be a little more intentional, I think, if you’re an entrepreneur to create a framework that allows you to constantly learn and get the mentoring that you need. But in both situations, whether you’re playing the inside game at a Chase or you’re playing the outside game as an entrepreneur, you need to constantly be learning, constantly find individuals who can give you feedback, positive and negative, and have a curious spirit along the way.

MS: Two quotes that you live by?

WC: That’s a good question. I live by a couple. From a business perspective, I often think of, “Think big, start small, scale quickly.” The other one, I won’t quote it correctly, but I’ll give you the concept, which is, “If you put something out into the universe, the universe will conspire to help you achieve it.” MoCaFi is a reflection of that, where I put this idea into the universe, and the universe has conspired to help me get to this point and achieve the vision.

MS: Well, ladies and gentlemen, I want to thank my brother, Wole Coaxum, whom I have the utmost respect for. I do believe you have a vision. Continued success on your raise. It is not average. You’re well above average as it relates to raising capital. You’re the consummate networker. You’ve created relationships that truly—you’ve read the room. So I want to thank you for being a part of rolling out here on CEO to CEO.

WC: Thank you so very much for having me, and I wish you continued success as well.