In the rarefied air of American dance, where legacies either crystallize or crumble, Judith Jamison stands as a towering figure who accomplished the near-impossible: transforming one man’s singular vision into an enduring cultural institution. As the longtime artistic director of Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, Jamison didn’t merely preserve a legacy—she amplified it, ensuring that Ailey’s name would resonate far beyond the confines of concert halls and into the very fabric of American cultural consciousness.

To understand Jamison’s contribution is to understand the delicate art of stewardship. When brilliant creators depart, their institutions often face an existential crisis. But Jamison—who had absorbed Ailey’s essence through years of dancing, interpreting, and breathing his choreography—approached her role with the same grace that marked her legendary performances of “Cry.” In her hands, Ailey became both noun and verb, a name that signified not just a company but a way of moving through the world.

What Jamison understood, perhaps better than anyone, was that Ailey’s work was never merely about dance. It was about transcendence. Under her guidance, the company became a vehicle for what one might call spiritual Afrofuturism, where every leap and arabesque carried the weight of history and the promise of tomorrow. In those moments when dancers took flight on stage, audiences of all backgrounds found themselves in what could only be described as a secular sanctuary—a church of movement where communion happened through gesture rather than gospel.

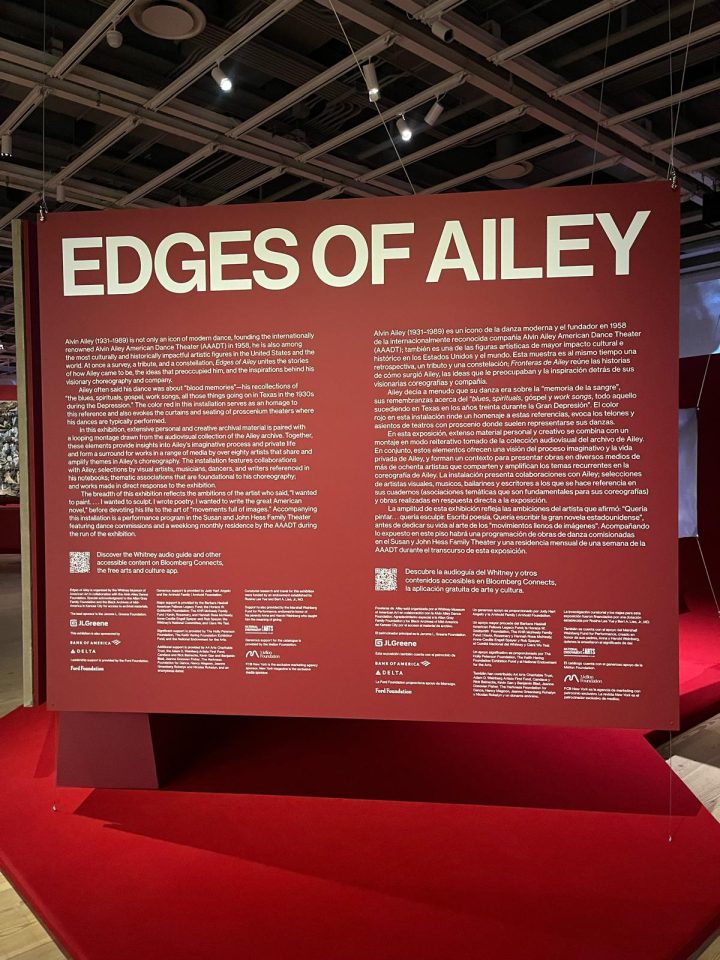

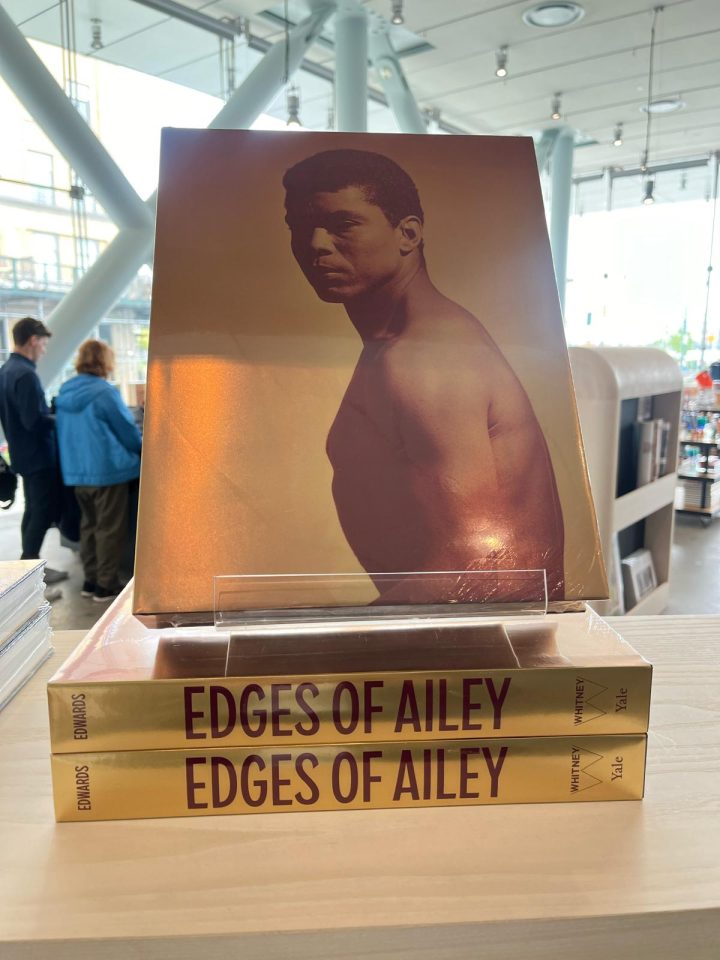

Like so many African-American women before her who have served as the unsung architects of American cultural institutions, Jamison became both keeper and creator. She maintained the sacred while embracing evolution, understanding that tradition without growth is merely taxidermy. When the Whitney Museum came calling, seeking to contextualize Ailey’s work within the broader spectrum of American art, it was Jamison’s steady hand that had positioned the company for such recognition.

The true measure of her impact lies not just in the preservation of Ailey’s choreography, but in the creation of a space where young Black dancers can see themselves reflected in excellence. Every time a child watches an Ailey performance and sees possibility incarnate—bodies defying gravity while celebrating their cultural heritage—they’re benefiting from Jamison’s devotion to ensuring that this platform would endure.

What makes Jamison’s achievement particularly remarkable is how she made the herculean seem effortless. Those who know the dance world understand that nothing about running a major company is easy—let alone one carrying the weight of such cultural significance. Through good times and bad, she created a foundation so solid that the company’s success appeared inevitable, though those in the know understand it was anything but.

Perhaps it’s time, then, for a standing ovation that extends beyond the theater walls. For Judith Jamison has done more than preserve a legacy—she has shown us how tradition, when properly tended, doesn’t calcify but rather becomes a living, breathing entity that continues to inspire, challenge, and elevate. In doing so, she hasn’t just honored Alvin Ailey’s vision; she’s ensured that future generations will have a home where their artistic dreams can take flight, where their cultural heritage is celebrated, and where the profound beauty of Black creativity continues to transform the landscape of American dance.

Watch an Ailey performance today, and you’ll see more than dance—you’ll witness the transfer of emotional, intellectual, and physical property into the very consciousness of America. In those held breaths and wide eyes of the audience, in those moments when people of all backgrounds experience church in the concert hall, you’ll find Jamison’s greatest achievement: the preservation of a dream that continues to exhilarate the imagination of all who encounter it.