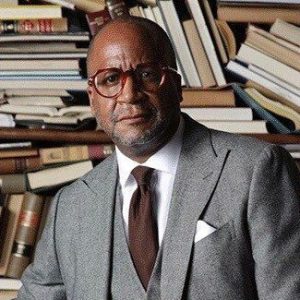

Stacey M. Gatlin is a passionate advocate, entrepreneur, and connector on a mission to rewrite the narrative of Black adoption and foster care. As the founder of Yes We Adopt, she and her husband embarked on this transformative journey after noticing a glaring absence of Black families in adoption training sessions. This observation, coupled with a desire to challenge stereotypes and amplify Black voices, fueled the creation of a community-driven platform that educates, advocates, and empowers.

With a background in corporate operations and a heart for service, Gatlin’s work extends beyond the personal. She serves as a Court Appointed Special Advocate (CASA) in New Jersey, advocating for children in foster care. Through Yes We Adopt, Gatlin seeks to debunk myths, foster meaningful conversations, and provide a safe space for adoptees, birth parents, and adoptive families to share their stories. Her work not only highlights the importance of mental health and community support but also serves as a call to action for Black families to explore the formal pathways of adoption and fostering.

Stacey M. Gatlin’s story is one of resilience, purpose, and unwavering commitment to transforming the adoption landscape, making her an inspiring leader and a voice for change.

As a leader in the adoption and foster care community, what inspired you to start Yes We Adopt, and how has your vision evolved over time?

Yes We Adopt was started because my husband and I noticed we were the only Black couple in the information and training sessions when we were on our adoption journey. We thought it was interesting that we never saw anyone Black considering adoption.

We knew that Black people adopted formally. In our network of friends, four other couples in our network had adopted through various pathways including internationally, private adoption, foster care, and through an agency. We were also disappointed that we didn’t see anyone who looked like us delivering training or leading conversations about adoption. I spoke to our adoption agency counselor and asked, “Why weren’t there more Black families?” and she responded, “It is hard to find Black families available to adopt.” My mind was blown away with this response. I told her about our friends and said yes, we adopt. Black people do adopt formally and informally. We thought we needed to get more Black individuals and couples to consider adopting and “Yes We Adopt” was created.

Over time, I started to listen and learn more information and recognized the issue wasn’t singular in getting more families to adopt or foster. It was about amplifying our voices and rewriting the narrative about adoption in our community. Black voices are often muted, refuted, or diluted, especially for adoptees, foster youth, and birth/first parents.

What are some of the biggest health and wellness challenges facing children in the foster care and adoption systems, and how does Yes We Adopt address them?

I believe the biggest health and wellness challenge for children in care is the toll of trauma and access to mental health support. The adoption industry is often depicted as unicorns and rainbows, as it relates to the adoptive parent and adopted child. In the foster care system, children are separated from their family and placed in care because the parents are unable to meet their basic needs. The goal of foster care is to reunify children with their family once the parents are stable and compliant with the service requests. But what we see depicted is negative family turmoil.

The goal is for family reunification. What adoptees will often say is adoption is trauma. The trauma is caused by the separation of a child from their parent(s).

How do you view the importance of mental health support in the adoption process, and what are some of the initiatives you have in place to support adoptees’ mental wellness?

Mental health is an important factor throughout the adoption journey for each member of the adoption triad (adopted person, birth/first parent, and adoptive parent). Each party can have their challenge.

Birth/first parents need to have support, especially with the difficult decision to place their child up for adoption. (They do not “give up” their child.) The mental health support is critical so they are clear in their decision, don’t feel pressured, and have the necessary support post-placement. Many women experience post-partum depression after giving birth. This could be compounded with feelings of decision remorse, guilt, shame, and other negative thoughts after the child is placed with the adoptive parents and the irrevocable period has ended.

For adopted parents, they must approach their adoption journey with the right mindset, especially if they are coming to adoption from a place of “loss” due to infertility or the loss of a child. They need to do their healing work to ensure they are coming into parenthood as a “whole” being. A healthy parent creates a safe and healthy environment for trust and bonding with their child. It is crucial they don’t view the (adopted) child as a “replacement” for the child they lost. The child has her or his own origin story and it should not be erased or overlooked. Post-adoption depression is similar to post-partum depression and is more common than people realize. It affects 18-26% of new adoptive parents who often suffer in silence because post-partum is often associated with biological factors and many adoptive parents think they’re exempt from it.

The most critical mental health support is needed for the adopted child to assist with feelings of identity, abandonment, and unanswered questions. Adoptees are statistically known to be more at risk for mental health problems, both due to the initial trauma and genetics. It is often recommended to provide adopted children with an adoption or trauma-informed therapist, but they don’t usually service children under 9 years old. Also, keep in mind the birth/first parent and adoptive parent are adults with life experience and need help in how to communicate their feelings, process emotions, and seek help. As with many children, these are new unlearned skills so adults have to demonstrate and provide the resources for children to feel safe in sharing their emotions. Sadly, adoptees are more than 4 times likely to attempt suicide attempt compared with non-adoptees.

Mental health is not an initiative for YWA, but we discuss its importance and share resources in our community and during our events or trainings.

What role does community support play in the success of your organization, and how do you foster a sense of belonging for families and adoptees?

The African proverb, “It takes a village to raise a child,” is more than a saying. The community or YWA Village is a vital reminder that we are not alone in our experiences and we need each other in this journey. Even though adoption is not often discussed, it helps to know a community exists to share stories, provide encouragement, and debunk myths like Black people don’t adopt. This applies to the adoption triad because we all need community, hope and love in our respective journeys.

As a CEO, what are the key leadership principles you adhere to that help Yes We Adopt make an impactful difference?

The key leadership principles I strive for are integrity, vision, emotional intelligence, and resilience. Yes We Adopt was created out of a need, so I strive to be purpose-driven in what I do vs. just being “busy”. There are so many needs in the adoption community so it’s important to stay focused on my “why”, and my vision and set clear goals. As with any role, operating with integrity is critical. It’s not about building an organization or brand, it’s more important that people can trust you, your word, and your work. Strong emotional intelligence is necessary because we’re connecting with people who have been impacted by their unique adoption journey. As a mom, I have to be able to learn from and empathize with adoptees because it helps me to be a better parent to my son. Although it’s not often discussed, I also add the principle of self care. Building and leading an organization, while parenting is tough. When I take time for self care, I am a better leader, wife, and mom.

How do you approach building partnerships with healthcare organizations, and what role does access to health resources play in your organization’s mission?

Healthcare organizations are not on my radar in support of the YWA’s mission, however, I do collaborate with adoption agencies directly tied to adoption and organizations that work in the adoption arena.

What advice do you have for other CEOs in the nonprofit sector on balancing social impact with operational sustainability?

Yes We Adopt is currently applying for non-profit status, however, I believe non-profits are often a combination of “head + heart” work. The “heart” is where people can align and rally behind a common cause. Non-profit leaders know how to market and tap into an invested or affinity community. The challenge we often see is that the “head” part of strategic thinking, long-term investing, and the ability to pivot is lacking. Non-profit leadership is more than just raising money; it includes managing finances efficiently to ensure the funding supports the mission and operational costs to sustain the organization.

Can you share some of the most transformative stories or outcomes you’ve seen through Yes We Adopt’s programs?

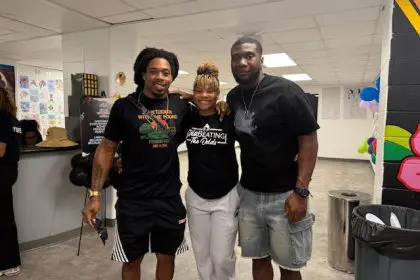

The Yes We Adopt Summit has been the most impactful event because it gathers a constellation of lived experiences. I’m sure there are more breakthroughs, however, I’ll gladly share three simple outcomes that assist with providing hope, community, and love.

An adult adopted person shared that the YWA Summit provided a safe space to share his thoughts. He felt seen and wasn’t alone in his adoption journey. He found out he was adopted when he was 11-12 years old. He is sad and probably had questions at that age, but his adoptive parents told him he had nothing to be sad about and told him to go outside and play. He felt muted for 25+ years because he couldn’t talk about his adoption.

Many people initially perceive birth/first mothers as evil or not caring about their children or they assume it’s like a Lifetime movie where it’s a young teen on drugs. A birth/first parent was able to share her story about how she chose adoption for her son out of concern for her son’s well-being. She was an educated young woman. When people heard her story, they looked at her with empathy vs. disgust and disdain. Her story rewrote the narrative about how birth/first mothers are perceived. When we share our stories, we become a more informed and engaged community.

During our recent YWA Summit on November 9, an audience member who was interested in adoption stated she changed her language based on the discussions she heard throughout the day. She wants to adopt a baby that she and her husband could love, raise and nurture. She learned that the child she adopts will have an origin story prior to meeting her because s/he will be born to other parents. She recognized that no children are blank slates. They are always a combination of nature and nurture. Her role would be to nurture the development, strong identity, and character of the child.

In your opinion, what are the most important health and wellness conversations that need to happen in the adoption and foster care spaces today?

We need to release the family secrets that parents want to take to the grave because those secrets are putting people in the grave. These secrets are lies that root and fester all to “save face” while the adopted person is struggling with their internal thoughts that they are afraid or forbidden to ask.

Looking to the future, what are your goals for expanding Yes We Adopt’s impact, and how do you plan to address emerging challenges in the field?

Some emerging challenges in adoption include the rise of DNA testing and ancestry websites. People may receive a DNA kit for the holiday and by the time the new year hits, they may discover surprising information that their parents may not be biologically related to them. The future of Yes We Adopt includes more community, education, and collaboration. We have a lot of work to do to educate the community, identify more Black families to consider adopting and amplify our voices.