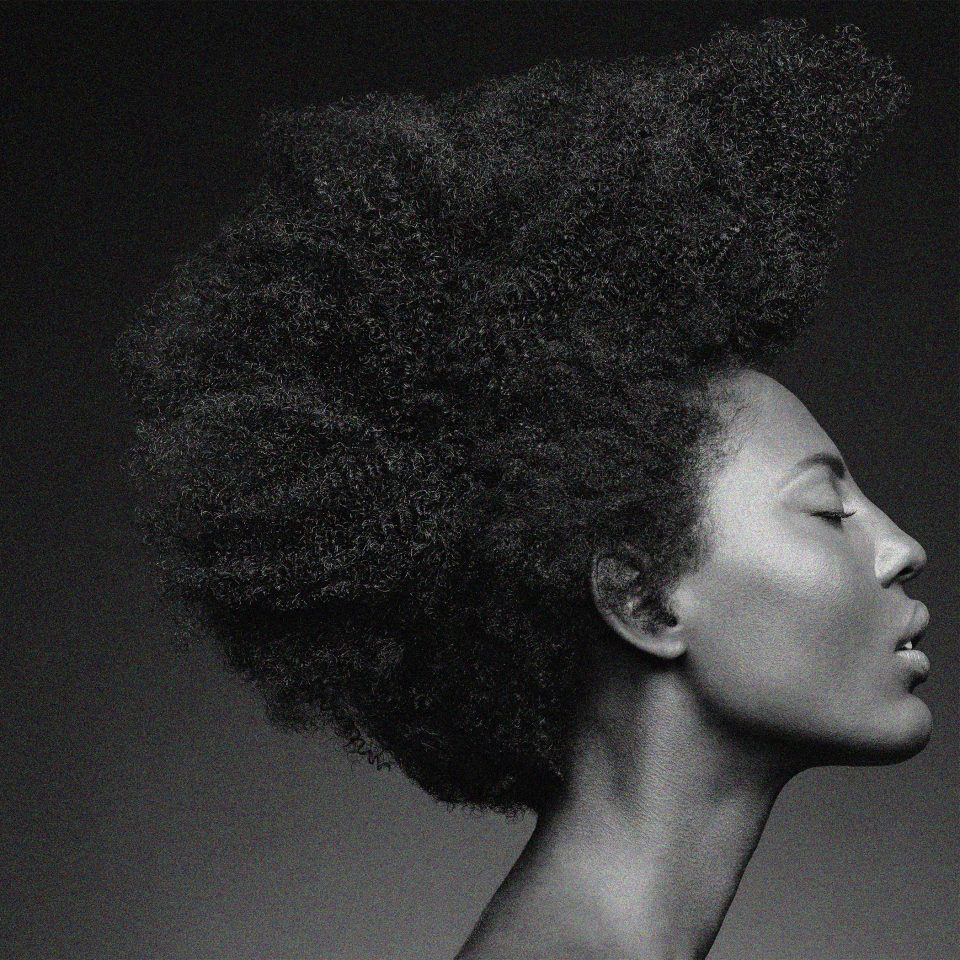

In the bustling heart of New York City, where fashion meets culture and art intertwines with identity, photographer Keith Major has spent three decades capturing the essence of Black beauty through his lens. A product of Brooklyn’s rich artistic ecosystem and a graduate of Rochester Institute of Technology, Major isn’t just taking pictures—he’s preserving cultural heritage, one portrait at a time. His portfolio reads like a who’s who of contemporary culture: Alicia Keys, Beyoncé, Kevin Hart. But it’s his work celebrating Black hair—in all its natural glory, innovation, and artistic expression—that has perhaps left the most indelible mark on the industry.

Major’s focus on natural beauty reflects a larger movement that has shaped not only artistic expressions but also the beauty industry. Over the past decade, natural hair care brands have emerged as cultural pillars, empowering individuals to embrace their identity. One such brand, Mielle Organics, founded by Monique Rodriguez in 2014, has revolutionized hair care with its dedication to nourishing textured hair using natural ingredients. From its humble beginnings as a kitchen experiment to its rise as a global phenomenon, Mielle’s journey mirrors the pride and authenticity captured in Major’s work.

Celebrating its 10th anniversary this year, Mielle Organics has become a leader in the beauty industry, offering flagship products like the Rosemary Mint Scalp & Hair Strengthening Oil, which have resonated deeply with women seeking effective solutions for their hair care needs. The brand’s partnership with Procter & Gamble in 2021 expanded its global reach, while its philanthropic efforts through the Mielle Cares Foundation continue to empower communities with scholarships and resources. Mielle’s growth underscores a shared mission with artists like Major: to elevate the richness of Black identity and inspire generations.

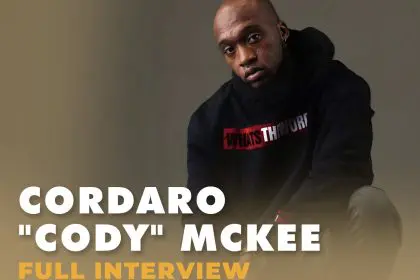

In this intimate conversation with Rolling Out’s Munson Steed, Major reveals how his childhood immersion in the “Black Is Beautiful” movement of the 1970s shaped his artistic vision and why he considers himself more than just a photographer—he’s a custodian of cultural memory. From his early days studying under photography legend Anthony Barboza to becoming a mentor himself at Parsons School of Design, Major has maintained a singular mission: to capture and elevate the inherent beauty of Black culture, particularly through the art of hair.

[Editor’s note: This is a truncated transcription of a longer video interview. Please see the video for the extended version. Some errors may occur.]

Being a creative whose instrument happens to be a beautiful camera and then being able to transform women, how do you imagine the future will be given that you can continue to do more and more with that lens each and every day?

I’ve begun mentoring and teaching a lot, and I see a lot of great young creatives carrying that torch. I see that as my mission—to impart knowledge and to encourage and to help those young creatives going forward. I was taught by Anthony Barboza, and even though I went to college and high school for photography, I probably learned more in four weeks with Tony than four years of college. That mentorship situation is a very good one, and I care a lot about our people, so I want to be there for them.

Share your journey on making hair in your lens art.

I have to attribute it to being fortunate enough to grow up in the 70s. In my household, we were indoctrinated with the Black Is Beautiful mantra. I remember my aunties, sister, mom rocking afros and rocking natural hairstyles. The photographer Kwame Brathwaite was famous for pushing the Black Is Beautiful mantra through his photography. Being a student of that school of photography, it became part of my lexicon. Even when I was testing young Black models, being a youngster myself, I felt like I wanted to make sure that the sisters had photographs just as strong as the white models. Working with our people and doing those ads, there’s definitely a sense of pride for me and a good feeling of accomplishment when you’re on a team of people of color in leadership positions.

You paint with your lens. How do you see art so that the subject, the consumer will pause to gaze at what you have in these images?

I started as a youngster as an artist. I wanted to be an artist, but my draftsmanship was a little janky. Like I wasn’t the best drawing, couldn’t render as well as I would have liked. Serendipitously, I ended up in a photo class and fell in love with it. I remember saying to my mom, this kind of satisfies that need because now I don’t have to try to be a draftsperson. I am definitely a fan of all of the arts. My inspirations come from movies, they come from plays, they come from the gallery, painting, music, and I pour all that in.

When it comes to my portraiture, I believe that I’ve been given a gift from God because what happens for me is I look at people and I see everybody’s beauty. I was once eating lunch not far from the studio, and I saw this woman with her family, great personality and just warm and loving. But she had what would be described as a deformity on her face. And I could see her beauty, and I was caught in this weird vortex because I didn’t want her to think I’m staring because she looks a certain way. I’m staring because I’m fascinated that I really can see this person’s beauty.

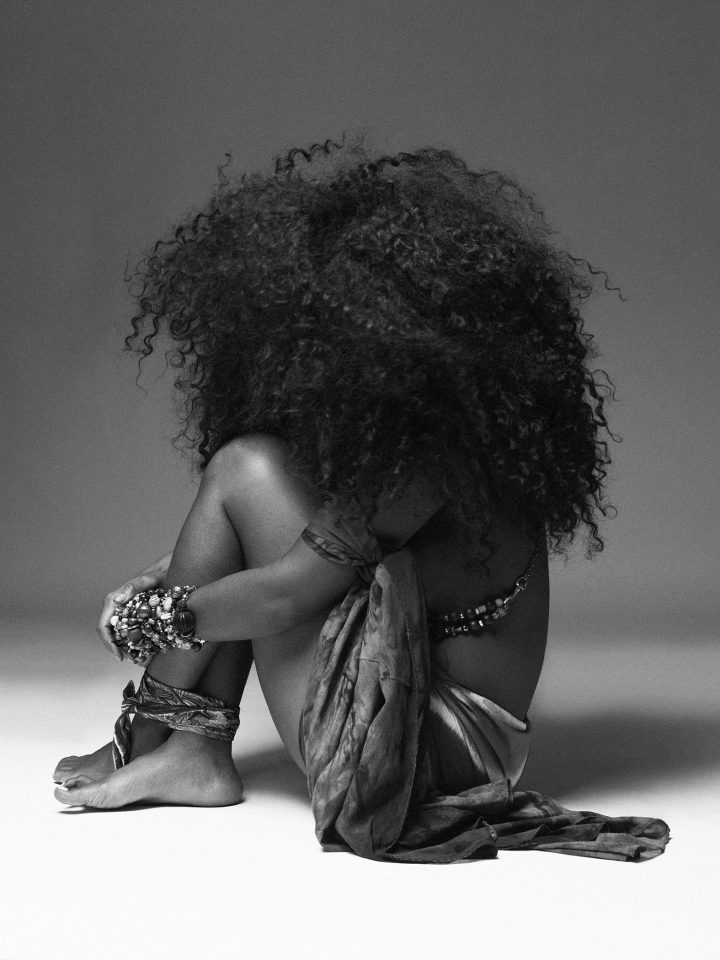

The cubism and dimension you allow in the images makes both the hair and subject speak. How do you achieve that?

I just finished teaching a portrait class at Parsons, and I imparted that with fashion and beauty, it’s really portraits. You want to take in the personality. You got to respect your subject, first of all. Secondly, you got to pay attention to what lenses you’re choosing. Many of those images were shot with what’s called a portrait lens, a beauty lens. When I’m doing a beauty shoot targeted for the younger market, I will literally pull a normal lens out because the younger market tends to like their images to look natural, almost like it was snapped on a phone. It’s like a way to apply the science to the look. I’ve had a lot of training and experience in the photo arts, and when I put that all together with my desire to do good work and do right by the subjects, it comes together nicely.

What styles have you enjoyed that seem to always return over the decades?

It starts with the Afro. If I’m doing it just for my book or for my pleasure, I tell models, you’ll have a harder way to go with me if you’re not coming with a natural hairstyle. Like if you’re coming with a weave or something straight, it’s not that I’m hating on it, but it ain’t my favorite. Then it becomes all the derivatives. The tangent to that might be the cornrow. I enjoy cornrows, and I like seeing how they can be manipulated and changed. I have photographs where the front of the hair is pulled back, and the back is a big Afro puff. My favorite looks always derive from black folks’ natural hair state and those styles that are native to our experience and our style.

Your work in New York includes Afro Latina subjects. How does that influence your perspective?

It’s fun. It becomes play, especially with the Dominicans. You’ve got all the flavors – from kinky curly natural to bone straight and all the colors of the rainbow. I’ve been fortunate enough to make a living at something that I would do for free. Sometimes I laugh and joke with them because I can give direction on hair and hair styling as if I was wearing the hair myself. It’s been a great ride, man. It’s fun for me being the guy that I am, I’m allowed to have the gaze, allowed to gaze at the beauty of these women and all the flavors that they present.

When a model isn’t comfortable with their hair, how do you build their confidence?

Usually they’re right on board once they see it. Very often I’ll get the “wow, I’ve never seen a photograph of me that looks this good.” If the person is really insecure, I know it’s my job to make sure that first image is a good one so that I can push the confidence. Because if I take a photograph that isn’t quite right, I may lose them. And so, it’s really important that I take my time and make sure the first image is a really good one. Fortunately, because I have the gift, it’s been fairly easy for me to get something good because I already see that beauty, and I’m just interpreting what’s there.

If your work was exhibited at the Whitney or the Met one day, what would you name the hair section of your show?

The first thing that comes to mind, I would give homage to Kwame Brathwaite and call it Black is Beautiful 2.0. That was a photographer who started that movement. It definitely left an indelible mark on me and I’m just part of that lineage. Under the heading would be the continuation of the celebration of Black beauty. You know, that was a photographer who started that movement. It definitely left an indelible mark on me and I’m just part of that lineage.

Why is it important for us to understand that natural beauty can be embraced without worrying about mainstream society’s views?

I think it’s important for Black love and Black pride. I think it’s fine to wear weave. I think it’s fine to wear a straight hair wig. But what I hope happens is this is a choice because you like the way it looks and not a choice because you feel like your hair is inferior or not good or, quote unquote, ‘bad hair.’ I think it’s important to promote natural hair because you have people that maybe can’t afford to change their hair, so we need them to be able to believe in their beauty. I have this unfortunate term that I use that I try to keep to myself. But every now and then I look at the straight hair and I call it the mark of the oppressor, which is kind of awful. But for me, I just want us to be proud. That’s how I grew up. I can still see my mother in the Afro.

When you look at women who’ve started to mature and you have to encourage them to explore new hairstyles or embrace their color, how do you approach that?

Even as a young photographer, I tended to prefer the older person to the younger person. The older person has more experience, and that life experience becomes more confident over time. Women are much stronger than girls, and I prefer women. A woman of some experience and some means is a very special thing. I find gray beautiful. I don’t see gray as age as much as a natural highlight. People will go to a salon to get blonde highlights, and I feel like people of color have the fortune of growing those highlights in the form of gray hair. The sisters that we’ve seen that have kept their gray and wear it proudly tend to be the more beautiful older women, because that confidence is a key component of extra beauty points. My dialogue is always positive about the aging process with all of the sisters.

If you were giving a speech at Spelman or Howard about hair as art, what would be your message to young women?

Adorning Oneself from the Inside Out: The Reasons Why It Counts. Because sometimes that beauty that you’re putting out is a reflection of what’s going on inside you. We have to remember the responsibility part of it might be: What is a young Black girl going to see when they see that? How I carry myself, what is a young Black person going to see in the way that I carry myself? There is a responsibility at times to be careful of how we move and show our best. I talked to a brother a while ago, he was selling some product, and I had to buy some product from him. And as I went to pay him, he said, no, don’t pay me. I got you. And I’m like, wait, what? And he said, listen. You know, I came to your studio on some business, and you and I were the only Black guys in the room, and the way you handled yourself. And I watched you, the way you moved. He said, you were just being yourself. And he says, I didn’t even know that was possible. That gave me confidence in my business to be able to go forward and do things.

Complete this sentence: “Hey, young lady, you’re wearing a crown, it’s art…”

Hey, young lady, you’re wearing a crown. It’s art. And I love and appreciate you for all of us.