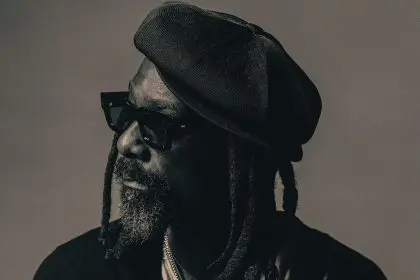

Before dawn, Charly Palmer listens to an inner voice that drives him toward excellence. This relentless force has shaped him into an artist whose work does more than decorate—it transforms. A winner of the Coretta Scott King John Steptoe New Talent Award for Mama Africa! and the NAACP Image Award for The New Brownies’ Book, Palmer has built a career illuminating Black history, from the Middle Passage to the present.

From his Atlanta studio, where the spirit of civil rights giants lingers, Palmer creates across mediums, from children’s books to a U.S. Post Office stamp honoring Judge Constance Baker Motley. His formal training at the American Academy of Art and the School of the Art Institute in Chicago laid the foundation for a style that graces TIME covers and private collections alike.

More than an artist, Palmer is a visual historian, ensuring the depth and vibrancy of Black experience remain seen, felt, and remembered.

How did you begin to recognize the need for the stories and communication you brought to the world?

It was really about having a true love for the black community and having a really strong love for our history and our story. I was like, how do I make? How do I carry that passion into something visual? It came from the standpoint of that connection, and I can start with our history. I started with the Civil Rights movement.

Actually, I started with the Middle Passage and Civil Rights movement. But it inspired me. I’m always uncomfortable when I see how we monetize our history. But it was a passion more than anything that made me want to tell our story.

What should people understand when they bring art into their homes and offices?

We hear a lot of times that our art should, as our library should be conversation pieces. If you want to get a really good sense of who somebody is, and you come into their house look at what’s on their bookshelves and what’s on their walls.

Even bolder statements is what’s on their wall when they go to their office, because too often, like an African American, is in a white environment. They try to wipe down their beliefs. They try to whitewash it. But when you see a Malcolm X and when you walk into a black man’s office in a white environment, he’s letting me know right away who he is.

Our children in particular, need to know who we are and where we came from. That gives them a sense and purpose of what they need to continue to do. It’s never been my intentions to inspire. It’s been more of my desire to tell truth.

How do you approach high-profile commissions like your U.S. Post Office work?

When you put it like that, it scares the hell out of me. If I was to pause and think like that, I would overthink what I’m doing. I look at Amy Sheryl. When Amy Sheryl did the portrait of Michelle Obama, she stayed true to her style.

I’ve said to people before, if given the opportunity, I might want to simplify it, because I don’t want people to misinterpret, because Amy’s style is hers, with the gray skin as opposed to brown or purple, or whatever. I want to tell that truth. When I was called by the U.S. Post office to do the stamp, it was one of my heroes. It was one of those easy things to do.

You’re going to pay me to honor one of these great legends of America’s history. I just want to do it justice. I want to honor them. It becomes really important to me, even when I can to speak to family members. What were they like? What would they have wanted?

I did a book cover of Dick Gregory, and once I heard the publisher was doing it, I called them and said, let me do this because Dick was one of my heroes, and I want to be able to represent him in the best light I can. I want to be able to try to at least express visually to some degree who that person was.

Who did you create the stamp for?

Judge Constance Baker Motley. An amazing judge, an amazing person. The more I’ve gotten a chance to talk to people about her – she was always on the right side or left side of Thurgood Marshall, but she was brave, she was bold, she was brilliant. When you get a chance to speak to people that knew her, she was extremely human.

In her personality she loved the garden, she was so many different layers, but I always admire, especially those that came before us, and how they would go into the trenches. But they’d go into the trenches prepared with brilliance, with information. They could debate you down because they had the facts.

Every once in a while, I just heard a name yesterday, and I’m going to start doing some research on this man because I don’t know much about his history. But he was a black actor that inspired Charlie Chaplin and W.C. Fields, and all these big white icons. But they all got it from him. It is important to say the names of people like Judge Baker.

How has being in Atlanta influenced your work, given its rich civil rights history?

W.E.B. Du Bois speaks to me even louder for two reasons. One is, my wife is a Du Boisian scholar. But he wrote Souls of Black Folk here in Atlanta. He was on the HU. He was on the campuses of AU campuses. I’m looking around, and when you mentioned Martin Luther King, the doctor, you see his name or his image everywhere.

One day I was talking to my wife, there is a small statue, a bust of Du Bois on the AU campus, and that’s it. I’m missing something. What am I missing? Because he wrote a book that to this day people still reference.

He’s been someone that has truly inspired me. And I’m curious to tell more about – you think about so many black legends that came through here, or a part of this. Maynard Jackson? I would think there would even be more presence of a Maynard Jackson here than what there is. But there is a presence of Maynard Jackson.

How do you approach designing so that the voiceless have a new mirror to see themselves in?

I take it very seriously, and it becomes very important that I acknowledge those that are spoken about less, because we hear the same names over and over again, even when it comes to – I’ve had the fortune of doing a lot of children books.

There are certain people that keep coming up. What about the ones that we haven’t heard about, because some of them have done absolutely amazing things. In fact, many of them have inspired that generation that we speak about. I’m not a huge big fan of any particular sports team, but if I turn on a game I’m going to start going for the team that’s losing.

It’s something about whoever’s losing. I want to see them win. And so I want to see these great black people that have come before us and those that are happening now. I want to see them win.

For young artists who are just getting started and working to find their voice, how did you find your voice in history?

I’m glad you used voice, because I use voice all the time. People take it so literal a lot of times. Of course, a singer needs their voice. They have unique styles in their voices. But even an instrumentalist has a voice. A writer has a voice, an artist has a voice. What I find, especially in the younger generation, is they want that voice to appear instantly.

It takes a long time to really, truly find your voice, and it comes from also the idea of what are you looking at? What are you reading? Who are you talking to? And those things are things that help to mold and form who you truly will be. Being still, which is very difficult for us to do, and being still and listening to your heart and your soul and your spirit.

Your voice will come out. I tell young people I work with, I mentor a lot of black artists, be patient with this. You’re going to be influenced by everybody. But at some point, if you’re true to yourself, yourself will come out.

What would you want someone to say fifty years, a hundred years from now about what you left for us to understand?

I put a priority on the children books that I do, because that’s the next generation, and I want them to know that they are loved. When I’m gone, if I can hear people say over and over again, Charly clearly loved black people. I say all the time when I speak to audiences of adults, they don’t intimidate or make me feel nervous.

But when I speak to children, I’m always nervous because their minds are still there’s space to learn and to be formed. I want to be conscious of almost every word I use, so I don’t try to dumb it down, but I also want to give them something that they can hold on to. I want them to say that Charly made a difference.

Whenever I encounter someone who says that you inspired me to be an artist, then I know that somehow I am doing my job.

Tell us about three of your favorite children’s books that you enjoyed designing that even adults could enjoy

The one that I just finished is one I’m probably the most proud of. I had a chance to work with the great Kwame Alexander. We have had that conversation for years, but he’s got a book called “How Sweet to Sound.” It’s the history of music. I would say black music, but all music to some degree is influenced and controlled and really created by us.

What I absolutely loved about the book was at the end, he gave texture and content to the story of Africa and the music that started there that evolved at Congo Square and New Orleans, and became jazz and blues and all these different things. He tells you the story of how it all started and how it all evolved. But he doesn’t go into that detail in the beginning of the book.

He does that after you’ve gone through all the illustrations he tells that story. I’m very proud of that, because it is that idea that we, as black people, influence and inspire everything.

The only book that of like 14 or 15 children books that I’ve done, I wrote only one, and it was based on growing up in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and going around playing basketball at all the different playgrounds and everything like that, and encountering some phenomenal talent, and many of those talented young men and sometimes girls we’ve never heard about again.

They never went past high school or college. It’s called “A Legend of Gravity.” I got lucky with that one, because I’ve attempted 4 or 5 times since then to write another, maybe 10 times. I’ve written 10 manuscripts, and I can’t sell another one. But something true came out of that first one the Legend of Gravity.

“Keep Your Head Up,” is one I did a few years back, and it literally was about a young black boy who wakes up and his day starts bad and his whole day gets worse. Who hasn’t had that experience? What’s so important to me about all of these stories is that it’s not about being black in America, it’s about being human in America.

I don’t even take on assignments anymore that are historical or black history, although I have an absolute passion for it. Can we tell everyday story about everyday children that happen to be black? Don’t give me a book that is about a white child. There’s plenty of white artists and black artists that will do that. Give me a story about a black child, but it’s not about his blackness, it’s about his different.

He may be quirky. He might have attention deficit disorder. He might be funny as hell it might be, whatever. But it’s not about being black. It’s about being human.

How can people better understand bringing energy into the room with the right art and movement?

Art is energy. I noticed that very early in my career. I was not responding to something that was necessarily well executed. It was what? What did it feel like? I’m feeling something right now. I said it once, and I’m really surprised because I hold on to it all the time now is, I said, that art should change the temperature in the room.

Sometimes it might be a cold feeling in that room, but a lot of time, it’s warmth, but the warmth comes from you. You get a sense that that image has love in it, heart in it, it’s got a story in it. Art should evoke a conversation, especially among generations. I was really surprised years ago, when I had done a series of black and white pieces that young people gravitated towards the black and white work.

I realized it wasn’t the colors. It was the imagery, and they wanted to know. I distinctly remember the moment when these children are responding to the image I had done a painting of John Carlos and Tommy Smith on a podium with their fist in the air, and a bunch of young people were around asking, “What are they doing? And we love this image.”

Then I had a chance to tell the story. That’s probably what should happen. Every one of you can make a difference like that.

I say that from a place of sincerity. I believe that when I’m speaking to 10 black children that one of these children could literally change this world, and I don’t know which one is going to be, because it’s not always the obvious one. Someone said the other day, I don’t recall where I was at, but they said that you’re never going to make it in this world as a C student.

The world is run by C students. They may have found their truth later on. It may have been politics. It may have been the position that they were born into financially. There are amazing, brilliant people in this world, but they’re not necessarily the A students. I’m not discouraging children from trying to get that A.

I’m saying, trying to get yourself trying to find and connect with who you truly are, and in doing so you’ll understand why God brought you here, and you’ll begin to find how you can really add your talent to this world wherever that might be.

How do you challenge yourself for bigger design ideas?

Great question. In mentoring, one of the things I noticed like in teaching and mentoring is that there are certain things that you do automatically. When you’re saying it out loud, suddenly, you realize, oh, yeah, I learned that when I was in college and I automatically apply that now. I have to be conscious.

I tell them a lot, if you are comfortable with what you’re doing, you’re not challenging yourself. If you feel safe in what you’re doing, you’re not challenging yourself. I realized once in talking to the group, wait a minute, I’m not challenging myself right now. I’ve gotten into this place where I’m very comfortable, so it’s time to make a pivot.

It’s time to change subject matter or change something. In making a conscious decision, there are certain subject matters that now I avoid, because I do that very well. And that’s easy. Let me do something hard.

One of my last assignments, I’m currently working on it right now is actually a story of Billy Porter. Billy Porter, what drew me to this? This book is called Songbird, and it was the idea that he found his voice. He was that different kid in school and he was really uncomfortable about it.

He was even fearful of singing out loud until he sung out loud and realized that he had a uniqueness in his style. What also intrigued me about the book? It was immediate concept, because it was called Songbird. I rarely ever paint birds. Birds are very different than anything I’ve ever painted before.

I want to do this, and I want to do it where it’s birds throughout every page. All kinds of different birds, and that was a challenge for me. And it is a challenge because I’m still working on it. Birds come in so many multitude of colors and sizes and everything, so that becomes its own little challenge.

I don’t want to get bored with this thing that I do. How do I push myself to do something a little bit different? That’s where I’m consciously making that decision now.

Who are some of your favorite legacy artists that really made a statement that allows you to keep going?

A couple of them are still alive. I absolutely love my mentor, Paul Goodnight! Because Paul was at what seemed like the top of his level with professionalism and success, and went back to school to get his Master’s degree. Everybody’s like, why is Paul going back to school? He already is doing it, and I only saw him get better.

A good friend of both of ours, Maurice Evans is a master colorist. It’s hard to explain that if you’re he’s an artist in that. If you look at him you’ll realize how he uses color. Nobody else does that. I like looking at those two because of how they approach life. But then, like Romare Bearden is a common one.

I just saw the giant show at the Hyde Museum, and there are certain artists, the scale of a Kehinde Wiley. It’s bold, but I like the approach of a Basquiat. Basquiat is somebody who’s been gone for 30 years. Damn if you don’t turn around, and there’s somebody copying another Basquiat. 30 years later, you still see the three-pointed star crown. You see that kind of impact. You see that influence in a lot of people.

If you were to listen to music, I’m still listening to Luther. I was listening to this whole week the early Jackson 5. I’m listening to Coltrane. I’m listening to the old stuff, and every once in a while someone will come along that I say this is fresh, and this is really new. I was talking to my youngest daughter the other day, and she loves Tyler, the Creator, and I say I see what he’s doing.

He is doing something very different. But what I love about like a Kendrick Lamar is that Kendrick has you thinking. I cannot think of much music that comes out these days that you’re trying to analyze and dissect and figure out. That’s what art is supposed to do.

That’s what happens with a lot of great painters is that every time you look at it you’re seeing something different, and writers, when you listen to their poetry or something, and every time you read it, or you listen to it, you hear something different. That’s the kind of stuff that keeps me going and keeps me inspired. I wake up so many mornings saying, and I don’t even know whose voice it is.

I’ve asked myself whose voice is saying to me do better. But I hear it. “Do better.” That means there’s some room to grow. That excites me every day.

How did the AfriCOBRA movement inspire you?

I wish there could be a movement like that today because so many artists came out of that. One of my heroes who was part of AfriCOBRA, Nelson Stevens. I was at an art show, and I met him. I had seen him in the seventies with the big black Afro proud and strong, and he walks in. He’s an older man, gray, short hair, and he says, “Young man, I like your work.” I shake his hand, he said, “My name is Nelson Stevens.”

I won’t go as far as to say, meeting God or Jesus, but you don’t understand. I used to look at your book when I was 10 years old, and one day I want to be a painter, and it was his work that made me feel that. The whole movement – there’s a need for a movement today like these men. Later on a woman joined them.

They had had a clear mission. Right now, we’re all over the place, but it’s like a clear mission. What is it that we are trying to communicate? What are we trying to say? It’s about black empowerment, black power.

We need artists to kind of come together again and figure out what movement is, something that we could all galvanize and help develop together, but also a certain level of that group of artists that even and like being in the presence of one another, elevates one another.