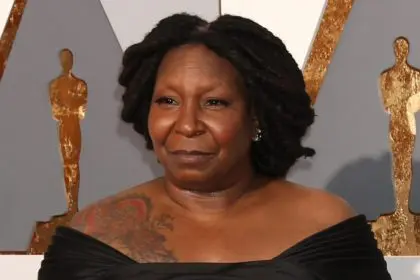

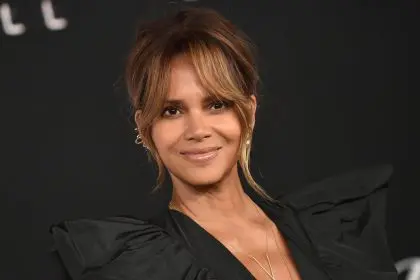

In the glaring spotlight of Hollywood’s highest honor stands Halle Berry, who in 2002 became the first and only Black woman to win the Academy Award for Best Actress. Her victory for Monster’s Ball was meant to signal a breakthrough, a door finally opened. Twenty-three years later, that door remains barely ajar.

“I thought that night meant things would change,” Berry says, her voice carrying the weight of decades of disappointment. “I stood there believing my win would usher in an era where Black women were regularly recognized for leading roles. That didn’t happen.”

Berry’s historic win remains an anomaly in an industry where Black women struggle for recognition in leading roles. Since Dorothy Dandridge became the first Black woman nominated for Best Actress in 1954, only 15 Black women have received nominations, with Berry the sole winner.

“The system is not designed for us, and so we have to stop coveting that which is not for us,” Berry reflects, recalling her disappointment when, in 2021, neither Andra Day for The United States vs. Billie Holiday nor Viola Davis for Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom took home the statuette. Instead, Frances McDormand won for Nomadland.

The supporting category tells a different, if still incomplete, story. Twenty-nine Black women have been nominated for Best Supporting Actress, with 11 winners. The journey began with Hattie McDaniel’s groundbreaking win for Gone with the Wind in 1940.

“They give us supporting actress awards like they give out candy canes,” says Taraji P. Henson, nominated in 2008 for The Curious Case of Benjamin Button. “The Academy doesn’t see us as leads.”

Most recently, Cynthia Erivo earned a Best Actress nomination in 2024 for Wicked, and Zoe Saldana became the latest Black woman to win in the supporting category. Their achievements, while celebrated, highlight the persistent disparity.

This pattern reflects deeper issues within Hollywood’s star-making machinery. Black actresses often navigate a system where they’re rarely positioned as the romantic lead, the complex protagonist, or the character whose journey drives the narrative. Instead, they’re frequently relegated to roles defined by trauma, servitude, or supporting others’ stories.

“The truth of the matter is, it is hard to get a job,” explains Davis, who won Best Supporting Actress for Fences.

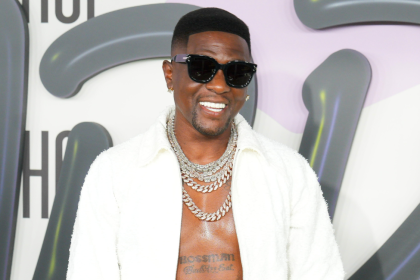

“You think all you need to be is the best actor that you can be and that is still not enough,” says Whoopi Goldberg.

Goldberg reflects on many of the roles that she received because a White actor or actress turned down the role. Shelly Long turned down Jumping Jack Flash, Bruce Willis turned down Burglar, Cher turned down Fatal Beauty, and Bette Midler turned down Sister Act which led to her role in Ghost. Patrick Swayze picked her for the role.

The documentary examines how these women have persevered despite the constraints, creating extraordinary performances even within limiting frameworks. It also spotlights those working to change the system — producers, directors, and executives fighting for authentic representation.

“I stand on the shoulders of women who worked so hard to be seen, and I exist because of them,” says Tessa Thompson. Black women are still fighting to be seen in this industry, not just supporting characters in someone else’s story.

As the documentary reveals, Black women’s journey in Hollywood isn’t simply about awards. It’s about the fundamental right to tell their stories, to be seen as complex, multidimensional leads capable of carrying films and capturing audiences’ hearts.

Until the day when another Black woman joins Berry on that exclusive list of Best Actress winners, her solitary statue remains both a triumph and a sobering reminder of how far Hollywood still has to go.