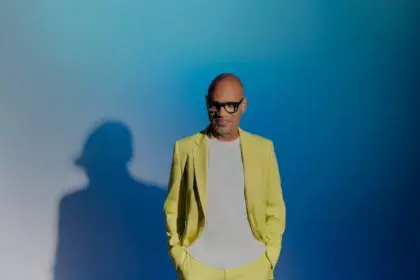

Jazz pianist Eric Scott Reed has spent over three decades crafting his musical voice, from his early days as a child prodigy in Philadelphia to his years touring with Wynton Marsalis and leading his own ensemble. Now, at 54, Reed is opening a new chapter with his latest release, “Out Late” – an album he describes as a convergence of over 50 years of life experience, spiritual growth, and musical evolution.

Born in Philadelphia and raised in Los Angeles, Reed began playing piano at age two and was performing in his minister father’s church by age five. His formal training at Philadelphia’s Settlement Music School and later at the R.D. Colburn School of Arts laid the foundation for a remarkable career that would see him work alongside jazz legends including Wynton Marsalis, Joe Henderson, Freddie Hubbard, and Elvin Jones. His albums have consistently charted on Billboard’s Top Jazz Albums, with three releases reaching the top 25.

With “Out Late,” Reed is offering something different, a raw, honest expression of his truth that goes beyond the technical mastery and reverence for jazz elders that defined his earlier work. It’s an artistic statement that reflects not just his musical journey, but his evolution as a human being willing to share his authentic self with the world.

How would you describe the musical journey you’re taking listeners on with Out Late?

I don’t know if I retain the right to tell people what they should be thinking. My main objective is for people to be open to embrace whatever it is I’m putting down. They don’t have to like it, but it would be nice if they did, with the understanding that as an artist, what I create is primarily for my own enjoyment, and it’s an expression of what’s within me. Hopefully I can share that with somebody else who might enjoy it, but as far as this latest release, Out Late, it’s sort of a convergence, a culmination of over 50 years of life experience, personal life experience, my spiritual life, my musical life.

If Out Late were a meal, what would you be serving as the appetizer?

It’s as if you are having a meal at a restaurant that is a direct expression of himself through food. For instance, you might get chicken, rice, and vegetables, but the way this particular chef makes his or her chicken, maybe with a certain oil, maybe with a certain spice that you can’t quite identify, but it’s familiar, because chicken is familiar, obviously, but the spices that are added are like, “Hmm! It’s more than salt. It’s more than pepper. It’s not garlic. It’s not onion. What is this? Cinnamon? Is this cinnamon in this chicken?” Because that would certainly be unusual, and I feel as though Out Late, with the analogy of it being a meal, you’re going to hear some familiar things by some familiar musicians. I mean, we’re all well into our fifties and sixties, so we’ve been out here for a little while. But you’re going to hear some things that you hadn’t heard before, and you’re going to hear and taste a little something that’s like, “I know this is familiar. I know this taste, but I’m not quite sure what this spice is. Do I like this? Hmm, okay, I’m gonna give this about five stars and come on back.” That’s what I’d like people to take away.

How has your approach to sharing your personal truth evolved as an artist?

It’s an interesting thing as human beings, and I’ll speak specifically as Americans. We have an idealized perception of individuals, and Americans are very in your face, very forthright. We often use euphemisms, but sometimes we’re just super direct, and we’ll just ask your business. For me, finally accepting and understanding that although the average person does not really want to know your truth. So for me, my truth is out here whether you asked for it or not. But you have invested in this project, and this project is an expression of my truth, whereas before, in previous projects and all throughout my career, I’ve pretty much just put the music forward and the ideals and ideas about jazz and living as an American, living as an African American, and what swing is, and being able to put the elders of the music on my shoulders, Art Blakey and Elvin Jones and Paul Chambers and Art Tatum, and I was walking around, and I made that my entire personality. So now, with Out Late, this is all my truth. I still have those cats, Clora Bryant and Betty Carter. I still have them right here, but I’m not really listening to them so much. They’re just there for support.

How do you want listeners to interpret your compositions?

With my music, there’s always a story behind every composition, but it’s like reading poetry or looking at a painting, people interpret in the way that it resonates with them. So I can say a song like “Shadow Boxing,” which is a song that I wrote for this wonderful drummer by the name of Ethan Kogan. He also goes by the name Shadow. I wrote it for him, and it’s supposed to be a drummer’s feature, which it is, doesn’t have to be, but that’s the way I wrote it, sort of in the vein of Herbie Nichols. It’s a drummer’s feature, and it’s supposed to exemplify the idea of the battles we face in life. The adversaries, and a lot of them, seen and unseen, often unseen, constantly boxing, sometimes boxing with yourself. But somebody else might say, “Well, Eric, I appreciate what you wrote and the narrative, but when I heard it…” My ear immediately goes, “Okay, what did you hear?” Because then I’m motivated and inspired even more by that person. As artists, we are not always the experts on our own works. We’re the ones creating them, but the interpretation is entirely individual. It’s up to the person that is embracing it.

What advice would you give to young musicians about authenticity and accountability?

I would encourage young musicians to always be honest in their intent, to always be authentic, but to always be loving with your gift. We’ve seen it time and again, where you have phenomenal artists who can write, sing, rap, produce, play, whatever it is, and audiences or their appreciators, music appreciators, dismiss bad behavior. Artists, we don’t get our coattails pulled enough because we have the talent. People see the dollar signs so often. People are going to be quick to say, “Oh, well, they’re just acting out. They’re just young, they’re just artistic. They’re just eccentric. They’re just unusual,” and somebody needs to say, “Hey, man, need to knock that off.” Accountability, I don’t think artists talk enough or converse enough, or even think enough about personal accountability. When you show up to the bandstand, how you show up, what you’re wearing, what you’re not wearing, how you’re speaking, how you’re communicating to the audience, how you’re communicating to the other people on the bandstand, how you’re receiving information, how you’re interpreting it. Just your energy on the stage.

If you could collaborate with Stevie Wonder, what would inspire that project?

I would ask Stevie, “Stevie, what influenced you in terms of literature, poetry, other songwriters, philosophers, icons of any kind?” Because it just seems to me as though Stevie encompasses a Utopian worldview. It’s like he embraces every and all things, and then he digests it, and then out it comes. How is this guy this in tune to life? I mean, the only other artists I can think of that impacted me that way, Nina Simone. Those two just endless pearls of wisdom being dropped and such unusual gifts. I wish I had a fraction of the courage, the bravery, and the fortitude of someone like Nina Simone. “Mississippi Goddam.” And speaking of social justice, she says, “Oh, I would lay down my life,” she said. “Everybody is willing to die, but nobody wants to kill.” I’m like, “Whoa, wait a minute. Now you’re talking some…” And what I appreciate about social media is that our young people are now finally being exposed to the words that are now 50 and 60 years old, of people like Malcolm X and James Baldwin, stuff that you and I grew up hearing in the neighborhood, and was powerful then. The world is catching up to them when they’ve been saying it all along.

How did moving from Philadelphia to Los Angeles impact your musical development?

I think it’s a story that I share with not only other artists, but with anybody who’s lived in various places in this country. The fact that the further east you go in this country, you see, it’s far more populated, and the further west you go, the states get bigger, and it’s less populated. LA is like the final frontier, as they called it. Growing up in Philadelphia and spending a lot of time in New York and also in North Carolina, there’s a certain type of intensity in the culture that has an impact on everyone that just is functioning day to day, and that’s going to impact the art obviously. Living in Los Angeles, which is a much bigger city and has sort of entertainment built in. The issue is, there’s no conflict, it’s sun shining every day. But the issue, or my observation about Los Angeles is that there isn’t enough conflict in the city to create art that can truly be taken seriously. Los Angeles has some great jazz musicians, don’t get me wrong: Scott Mayo, John Clayton, Billy Childs, Patrice Rushen, I can go on and on and on. But Los Angeles is so big, there’s no central location. There’s no one area where musicians can just all just converge, and you’ll see the entire scene. Unlike New York, Philadelphia, where the concentration is much smaller, and you can walk from one club to another.

How did you adapt during the COVID-19 pandemic?

When COVID hit, I, like every other jazz musician on the scene, panicked. It’s like, “Oh, my God! This is it? This is the Armageddon of jazz?” I said, “What’s going on? No gigs? Oh…” I said, “Okay.” So after I chilled for a second, I said, “Okay, well, I’m not about to get evicted because they’re not doing that. I’ll be cool. I got a little savings, but I don’t know what’s going on over there.” I said, “I’m about to turn this into lemonade.” I went to the piano. I said, “Well, I got time to practice now, since I ain’t got no gigs. I got all the time in the world to practice. Practice for what? There’s no gigs. Well, this can’t last. I’ll just practice, practice. So maybe I’ll go live. Yeah, social media? All right. Here we go. I can’t play live in a club. I’ll play live from my home. Here we go. Tune in folks. Okay. Good. Folks are sending me Cash App, Venmos, you pivot, and that’s what artists do. This is what we do, and I think it’s a life lesson for everyone. You just pivot.

What do you want audiences to feel when they see you perform live?

I want them to feel whatever they want to feel. I truly do. I want them to feel all of the emotions. There’s not a lot of anger in my music, at least not yet, or at least I don’t think. But I do believe there’s a lot of beauty, a lot of positivity, a lot of spirituality. I want them to feel all of that. I want them to be able to detect some of the moments that may have anger in them. They might not sound angry in the way we think angry music should sound. Sometimes it’s just a chord that I’m just rumbling, seething anger, sort of an undercurrent. I want them to feel whatever they want to feel, and hopefully be able to understand and sympathize, even if they can’t empathize. I want them to be able to sympathize with where I’m coming from artistically.