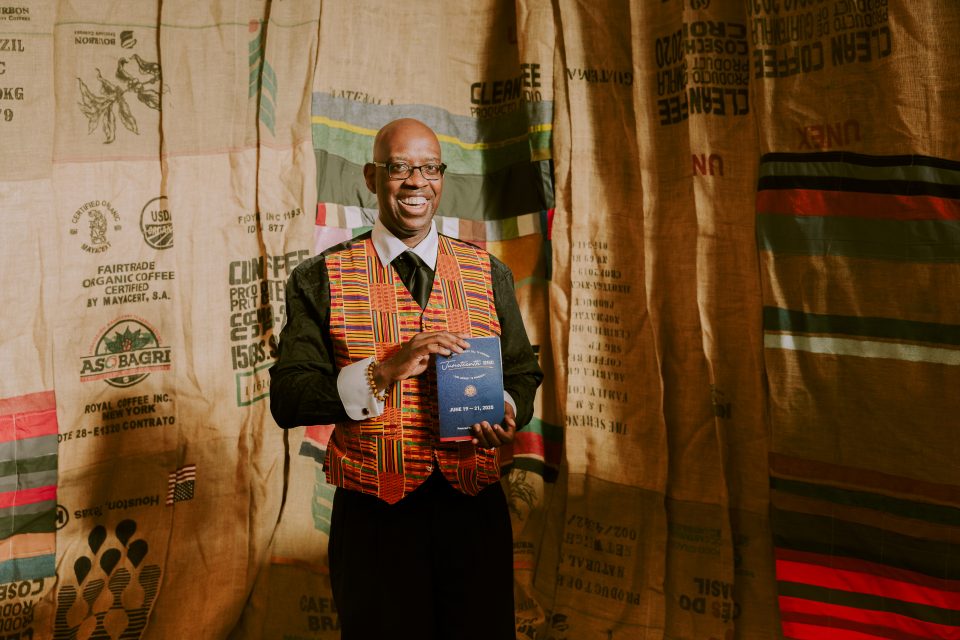

Alexis Pye’s uncle Jessie — affectionately known as Uncle Tootie — told her he lost his eye to a rogue parrot in a jungle when she was 6. Years later, she would learn the truth about his injuries from Vietnam and understand the tall tales as his way of processing trauma. Now, the Houston-based artist honors both her grand-uncle and Private Lewis in the Buffalo Soldiers National Museum’s “Terms & Conditions: The Promise vs. Reality,” creating works that challenge how we imagine Black military service across generations.

Known for placing her subjects in luscious, nature-rich settings that evoke playfulness and wonder, Pye brings a different approach to this historical exhibition. Her mixed media paintings, incorporating embroidery and punch-stitch needlework, explore how the American flag’s red, white, and blue mean different things across the color line. Drawing inspiration from Lucille Clifton’s poetry and conversations with fellow artist Tay Butler, she creates work that is both playful and deeply melancholic — asking viewers not to lack imagination for Black life while confronting the empty promises made to soldiers who fought for freedom only to return to sharecropping and oppressive laws.

Can you describe your artwork featured in the exhibition and walk us through your creative process?

The title of one of my works, “let the fields turn mellow for the men,” is taken from the poem Let there be new flowering by Lucille Clifton. The American flag work is based off two men. One is a direct relative, my grand-uncle Jessie Pye, and Private Lewis. My creative process was really to make a lot of preliminary drawings, and the ones that felt more connected to the subject matter. I didn’t think to use a relative at first. But then it hit me when talking to Tay Butler, speaking to him helped me put the prompt that we had in perspective. I was thinking about how war is an assault on youth, it takes a lot, where some feel over-exacerbated. Some leave with a patriotic pride, and a lot are left with wounds that affect them directly and indirectly. I thought about how the American flags never felt that big to me. Actually, it felt restrictive.

Empty Promises, my other piece — I was thinking of all the encouragement of leading young people to war. Especially the Civil War, to fight for your right to freedom. Yet when these soldiers come back, they see little change. Still working the same land, sharecropping for little to no income. Still returning to the same oppressive laws and lifestyles. Basically, an open-air prison, and we see this illustrated in different points of American history. Returning to the American Flag, how red, white, and blue might mean different things across the color line. Even looking today, some soldiers come out with more baggage than they came in with. Some are left behind, take their own lives, and are robbed of pivotal points of life. All in the name of America.

How does your piece speak to the meaning and legacy of Juneteenth?

I’m coming from a different perspective as a Northerner (coming from Detroit). What I bring to the table with these works is the importance of preserving these histories of Blackness in the military.

What role do you believe art plays in preserving and communicating Black culture and history?

It’s a visual language. I find it interesting how painting influences our visual iconography, especially in the West. There is so much uncharted, digested history through painting. I feel Black painters are catching up with four hundred years of painting. We are all creating, experimenting, and playing with time through visual storytelling.

How does your work reflect or challenge the social realities we live in today?

I’m a Black female painter. I’m challenging the painting zeitgeist by just participating in traditional painting. I’m challenging the medium by not taking the medium too seriously. The work can extend and play, but still stand in its meaning.

Do you see your piece engaging with themes of Afrofuturism or reimagining Black futures?

My practice is playful, but when you look closely, it’s quite melancholic. I think what I’m doing is asking people not to lack imagination for Black life.

What personal stories or emotions did you draw from when creating this work?

My Uncle Jessie, affectionately known as Uncle Tootie, was a very funny man. When I was young, my grandmother, his sister, would go over and take care of him. Well, it would be more like her doing basic tidying up and me interacting with him. He told me long-winded tales of how he lost his eye and his legs. It turns out he lost his limbs because of a series of unfortunate events, at the cost of his mental state after Vietnam, and along with his eye. For example, he told me that a 6-year-old lost his eye to a rogue parrot in a jungle. Also, with time, I learned about his decline after the war; he lived alone, and I like to think those times when we visited were the highlight of his week. He didn’t have a lot of visitors, and his only interaction was with immediate family and caretakers. He had a thunderous laugh, and it was very infectious.