Story and Images by Amir Shaw

Wasalu Muhammad Jaco lost his cool minutes before a scheduled sit down with ro. The 25-year-old Chicagoan was pacing back and forth anxiously at the sinfully luxurious Ritz Carlton in Atlanta. He was talking on a cell phone with an operator from the U.S. Department of State who would not be able to comply with his request. While Jaco maintained that he had already submitted the proper paperwork to the department in order to replace a missing passport, the operator insisted that he hadn’t. Realizing that his dilemma would take more time to resolve, Jaco turns the cell phone off in disgust and confers with his manager, J Boogie.

“What if no one could tell a lie?” Jaco asks his manager, who raises his eyebrows in response. “There wouldn’t be any newspapers, books or libraries. A lot of people would be out of a job. Especially [the operator], she’s definitely not telling the truth.”

Jaco, known to the world as Lupe Fiasco, has built a career on defining and examining the truth. On his four-time Grammy-nominated debut album Food & Liquor, Lupe intellectually challenged the status quo with songs such as “Hurt Me Soul,” “Real” and “He Say She Say.” And while we all fell in love with the jazz-induced skateboarding anthem “Kick Push,” the widely slept-on “American Terrorist” was an amazing social critique of America’s forefathers and their mistreatment of Native Americans, Africans and Chinese railroad men.

From that song alone, you can understand why Lupe doesn’t buy the warnings from Homeland Security or accept the imminent threats that are forecast by the National Terror Alert Response Center.

“For America to keep itself stable and to keep progressing, it has to instill fear and the fear of consequences,” Lupe says, now more relaxed in the conference room at the Ritz Carlton. “What America is doing [with terrorism] is no different from what happens with the Bible or Koran. To maintain a level of control, you have to instill a final goal of punishment or reward.”

click here to view Lupe Fiasco’s interview with ro

A devout Muslim, Lupe also believes that the media plays a major role in the perpetuation of religious and racial profiling. “I think there are certain suspicions about American Muslims because that is the face of danger that you see whenever you turn on the television,” he emotes. “But don’t get it wrong, the number one threat to America is still young black males. The idea that a young black male will grow [up] to teach other young black males to be wise and have power is still not accepted. I think they want to kill that idea early.”

That idea is often crushed and fails to come to fruition for many young blacks who reside in Chicago. According to statistics compiled by the U.S. Census Bureau, more than a third of Chicago’s black youth live in poverty, and 11 of the city’s 15 poorest neighborhoods are at least 94 percent black. In turn, Chicago has one of the highest incarceration rates for blacks in the United States.

Lupe was raised in the Maynard Terrace apartments on the turbulent Westside of Chicago. “When I was a kid, [there] was a lot of drugs, prostitution and gang activity going on right [in the neighborhood] where I lived,” he recalls. “But my household was the difference. I had an intellectual father who studied martial arts, and my mother was a great orator and chef. That was the balance. I was able to participate in a lot of positive stuff while in the realm of so much negativity.”

At a time when many of his peers were succumbing to detrimental activities such as drug dealing, alcohol abuse and drug use, Lupe was discovering creative ways to channel both his positive and negative experiences.

On his sophomore album Lupe Fiasco’s The Cool, Lupe attempts to alter young people’s attitudes about destructive behavior within the black community.

“Cool is all around us, saturating our culture. We can’t escape it. Cool informs both our mundane activities and our significant decisions. It is an attitude, a habit, a worldview, a feeling. Sometimes we control cool, but sometimes it controls us. And sometimes, cool reduces us to extras in somebody else’s fantasy — passersbys to whom he or she can feel superior.” –an excerpt from Blessed Are the Uncool: Living Authentically in a World of Showby Paul Grant

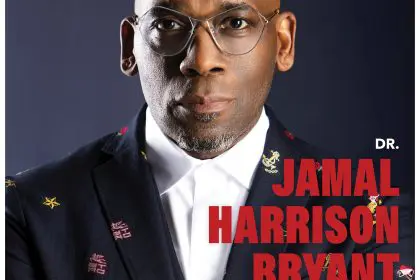

After attending a speech in which Dr. Cornel West said, “If you really want to effect social change in the world, you have to make those things which are uncool, cool,” Lupe found the inspiration to create The Cool.

“It’s basically about making it hip, or cool to be square and smart,” he explains. “There are things that are perceived as cool that are really not cool. And there are a lot of negative things that shouldn’t be cool anymore.”

Dr. West agrees with Lupe’s intent to initiate social change through hip-hop. “Lupe is one of the most creative, visionary and talented artists of his generation,” Dr. West said during a telephone interview from Germany. “If we can make it cool for young people to think critically and to muster the courage to love each other, things will change and everyday people will be empowered.”

Lupe took his inspiration several steps forward by creating a fictional world that revolves around the idea of what’s cool. “The Cool is a concept album about a boy who grows up without a father and becomes ‘The Cool,’” he says. “He didn’t have a father, so ‘The Game’ raised him. ‘The Game’ is a monster who has dice for eyes, bullets for teeth and breathes crack smoke. And once ‘The Cool’ was raised by ‘The Game’ he fell in love with ‘The Streets.’ ‘The Streets’ is this voluptuous temptress who has dollar signs for eyes. She’s very attractive, but she’s also deadly. I have five songs on the album where the story unfolds.”

Thus far, Lupe Fiasco’s The Cool has been critically acclaimed by The New York Times, The Boston Globe and Rolling Stone. It sold 143,000 copies in its first week and will likely earn him more Grammy nods in 2008.

The lead single “Super Star,” sums up Lupe’s feelings on the precarious music industry. Lupe says that the song is more about a public execution than a celebration of popular talent. “When we were coming up, we were told lies about the music industry,” he says. “We were told music meant having a record, a big house and a nice car. It didn’t teach us the sacrifices, the hurt and pain. The hurt and pain [are] trivialized by the press. They applaud the artist’s downfall and failure. But you don’t see that until you get here. You realize that there isn’t much substance in music. The real substance is reaching fans who really appreciate your words. That’s what I do it for.”