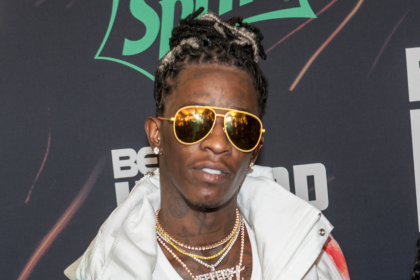

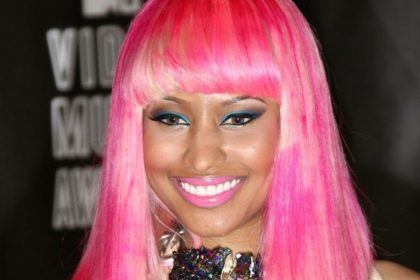

Last week, Young Money rapper Nicki Minaj debuted the artwork for her new single “Anaconda.” The racy pic immediately drew attention and criticism: it features Minaj in only a pink bra, some Jordan sneakers, and her infamous backside is prominently featured in only a G-string. Of course, she knew when she shot the photo that it would catch attention — and probably knew that she was going to catch a lot of flak for it.

And she did.

Within hours, the Web was virtually flooded with op-eds bemoaning the hyper-sexualization of black women, the brazenness of Minaj herself, the state of women in hip-hop and the objectification of women in the music industry. Over the next few days, “Open Letters” were written to Minaj (do celebrities ever read those things?) from prominent hip-hop websites and one from a “concerned father.” What a poor example Minaj has to be setting, allowing herself to be exploited for profit and publicity.

But the whole thing resembles sad comedy.

As anyone who’s been fairly awake for the last 25-30 years can tell you, male rappers have been objectifying women for decades. Beyond that, male artists in music have been objectifying women since the days of Led Zeppelin, the Rolling Stones and the Ohio Players. Rock stars and hip-hop stars become legendary for their sexual conquests, whether real or perceived, and a large segment of the hip-hop-buying public and hip-hop media seems to be fairly okay with Too $hort’s “Freaky Tales” or Lil Wayne’s “Lollipop.” We hail 2Pac as a legend and an icon for his emotional, introspective raps and his quasi-revolutionary rhetoric — while conveniently downplaying the sleaziness of raunchy songs like “How Do You Want It” and “Toss It Up.” Male hypersexuality and the use of women as ornaments seem to be par-for-the-course to many of us who love this thing called hip-hop.

So why did Nicki Minaj get people so worked up?

Why did we see this scantily-clad woman in a photo and suddenly become concerned for our daughters? These same publications and media outlets made stars out of “video vixens” like Rosa Acosta and Melyssa Ford. So if Nicki Minaj were just an anonymous “vixen” in a Lil Wayne video wearing that G-string, there would likely be little-to-no think-pieces from these individuals worrying about their daughters. Where are those open letters? Lil Wayne had to disrespect a slain Civil Rights icon to raise the ire of hip-hop media. All Minaj had to do was show her butt.

So much of our culture, as it pertains to sex and gender, is built on the idea that sex is driven by male desire and women’s acquiescence to that desire: men want sex, women “give up” sex to appease men. This conditioning is why we automatically view a sexualized woman as a victim: she must be exploited somehow or in some way damaged. We don’t view her as a person in control, doing what she wants to do — she’s lessening herself for the desire of men. That’s a puritanical generalization if ever there was one. And it denies a woman the right to decide who she is and what she wants for herself. It keeps her imprisoned in the dungeon of male judgment. Her sexuality doesn’t belong to her — not if we have anything to say about it.

Culturally, we have to come to grips with the fact that women are sexual–your mom, your sister and, yes, even your daughter is or will become a sexual being. And they have as much right to owning that sexuality as men. Even flaunting it.

When a man raps, sings or just brags about sex publicly, we don’t view him as a victim. We don’t hear Lil Wayne rapping about cunnilingus ad nauseum and think “It’s so sad that he’s exploiting himself.” We may think he’s gross–but we don’t think he’s being forced to do something that he doesn’t want to do. We don’t assume he lacks control of his music or image because of his racy lyrics. When considering objectification, one can’t just use the term recklessly; which is what the general public tends to do when the person being scrutinized is a woman. Nicki Minaj throws her sexuality in our faces and titillates because she wants to–the same as a male rapper who raps about his sexual exploits or parades around with ornamental women in his videos. An artist like Janelle Monae, for instance, deserves praise for choosing to cover up–not because someone said “This should be your image,” but because she decided that it would be. Don’t presume that Nicki Minaj is more victimized just because the image she presents is more brazen. That’s truly sexist.

If you discovered that male labelheads had forced Monae to wear suits, would you still think she’s a great role model? If so, you may want to ask yourself why.

There’s another troubling bit of hypocrisy in the reactions to “Anaconda” that Minaj herself acknowledged on her Instagram page. We walk past newsstands with women in string bikinis and thongs on the covers of Sports Illustrated and Playboy daily. When new Kate Upton pics hit the Web, are they tagged with headings like “raunchy” and “NSFW” simply because she’s wearing swimwear or lingerie? Nicki Minaj’s image wasn’t nude or explicit, why is it considered so over-the-top? Is a big, black booty more “offensive” than petite white women who are dressed similarly? The hip-hop “booty model” is stigmatized as if the world has forgotten that Tawny Kitean ever writhed all over a convertible in a Whitesnake video. In American culture, Black sexuality is seen as exotic and “other.” So it’s more “offensive.”

There are those critics that have railed against all of these things before Nicki Minaj and they will after. They complain about the male objectification of women and the female’s willingness to be objectified fairly equally. Which is their right; it’s still highly dubious–but at least they aren’t hypocrites. But there are also quite a few–particularly within hip-hop–who have been decidedly silent up until a few days ago. Once the furor over Nicki Minaj and “Anaconda” dies, will these concerned parties — those within the world of hip-hop media and culture — write more “open letters” about the objectification of women in the genre? Or will they go right back to glad-handing and celebrating the misogynist status quo that’s always been there? Is this the beginning of a sea change or just an opportunity to metaphorically stone a “non-virtuous” woman?

I guess we’ll have to wait and see.