Love it or hate it, “Empire” isn’t going anywhere.

Lee Daniels’ creation, the story of hip-hop mogul Lucious Lyon, his ex-wife Cookie and their three combative sons, has become the breakout hit of the season. Stars Terrence Howard and Taraji P. Henson have become two of the biggest names on television; having already scored in film as Oscar nominees in years past.

The show also has recruited an impressive list of guest stars; from Jennifer Hudson to Derek Luke to Courtney Love; as well as touted cameos from musicians such as Patti LaBelle and Rita Ora. Despite the ever-controversial Lee’s penchant for overstating (his belief that his show is “blowing the lid off” of homophobia in the Black community is a bit arrogant and the ongoing war of words between he and Oscar-winning actress Mo’Nique has been ugly to witness), the show has only grown in popularity since it debuted this past winter. And Lee obviously is enjoying the success.

And the backlash.

Daniels told Vulture that he’s enjoying watching audiences react to some of the show’s more “WTF?” moments, including a notorious scene involving actress Katelyn Doubleday, oral sex and a baby bib. “I think coming up with things that let us push boundaries, that you don’t think will actually make it on TV, and do, that’s what you get — you make Twitter, or whatever,” Doubleday said.

“That is what makes provocative television,” Daniels added. “Things that make you go, ‘Whoa!’ … The bib moment is my favorite.” And Daniels has also stated that the inspiration from the show, while acknowledging many contemporary hip-hop moguls’ stories, initially came from older icons; such as the stories of Berry Gordy and Joe Kennedy.

Citing legendary television producer Norman Lear as an influence, Daniels dismissed the networks as not having any faith in audiences. “The systems underestimate the intelligence of everybody within this room,” he said weeks ago at a screening for the “Empire” season finale. “Through humor, we would have liked to have the discomfort.” It would be a bit of a stretch to view the soapy prime-time drama as providing any tangible social commentary directly, but its success has driven a fascinating examination of Black content, Black audiences and what that means as it pertains to mainstream, White platforms.

The show’s finale drew an impressive 16.7 million viewers, according to updated Nielsen numbers, up 12 percent from 14.9 million for the previous week’s one-hour episode. “Empire” ended the season as the top-rated network series among viewers ages 18 to 49, a major coup for an African American midseason show that was only generating lukewarm buzz prior to its premiere back in January.

“Empire’s” success is the feather in the cap for a TV season that saw a mini-resurgence in African American scripted shows. On ABC, the “Shondaland” Thursday night lineup added “How To Get Away With Murder” and on Wednesdays, “black-ish” became a solid follow-up to mainstay “Modern Family.” On basic cable, OWN and BET have “The Haves and Have Nots” and “Being Mary Jane.” On premium cable, STARZ unleashed two new shows in 2014, the crime drama “Power” and the dramedy “Survivor’s Remorse.” On Nickelodeon, Tia Mowry stars in the PG sitcom “Instant Mom.” There is an expected TV version of the popular 1989 comedy Uncle Buck, that will reportedly feature Mike Epps and Nia Long in the leads.

The success of “Empire” brings with it some necessary questions about African American entertainment and what the public tends to gravitate toward. Critics of the show point to its premise — a former drug dealer-turned-nefarious hip-hop mogul running a label with his ex-convict wife — as a stereotypical presentation of Black people as criminals and associated with thuggery. Dr. Boyce E. Watkins recently engaged in a debate on CNN centered around this very argument; having already written an opinion piece that proclaimed he would not support the “coonery” of “Empire.” But in a television age when most popular shows feature behavior that varies from despicable to criminal to unforgivable, is it realistic to believe that Black shows can thrive by presenting wholesomeness? How many of those who criticize “Empire” watch PG-rated television or movies? It seems hypocritical to blast “Empire” if you’ve got shows like “Ray Donovan” or “Game of Thrones” set in your DVR. We enjoy watching people behave badly.

And more than that, actors, writers and creators should have the latitude to create as they see fit. As opposed to stifling their creativity and demanding that they pander to racist attitudes. Taraji P. Henson’s Cookie has become one of television’s most popular characters, and the actress says she looks forward to tackling any role that isn’t “safe.”

“As an artist, I don’t like to do safe work,” she told E! News back in February. ”I like to do work that is going to push people to think. That’s what art is supposed to do. If art really imitates life, it isn’t going to be so pretty. People are going to disagree. There’s going to be hate, there’s going to be love, there’s going to be conflict. And that’s what I love about this show. Because it’s not safe at all.”

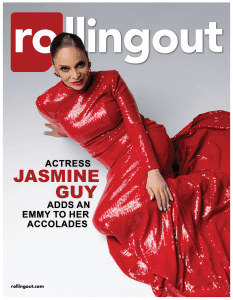

Her co-star, Terrence Howard, came under fire for suggesting that the show should use the N-word, a statement that seems beyond the pale for prime-time network TV. “If we start getting silly, if we start playing to people’s fancies, then we don’t deserve to be where we are,” Howard told Entertainment Weekly. “It’s a big pressure because I want to be a truth sayer. I want to raise the bar,” he said. “I want to get rid of this f—ed up word called PC. I think it’s a gate for bigotry because as long as you’re politically correct, you can say anything you want but feel some way different.”

Howard’s notions about the N-word on TV are highly questionable — as is his disdain for what he deems “PC,” but the idea that Black folks have to sanitize Black culture for White consumption is something that should be challenged.

“Empire” caters to the same kinds of audiences who loved “Dallas” and “Dynasty” in the 1980s; it’s an over-the-top nighttime soap that presents outlandishly contrived storylines that are entertaining and compelling because they are so outlandishly contrived. Lucious Lyon is a bad person, that is without question — but most of our favorite TV protagonists have been bad people over the last 15 years. And as far as how Lyon “makes Black people look,” we should really begin to examine our fixation with respectability as a cure-all for racism. As of right now, it’s hard to argue that Lucious Lyon is a more visible representation of Black maleness than, say, Barack Obama or Will Smith or Denzel Washington or Jay Z. So why is he the definitive portrayal in the mind of anyone except those who already embrace racist ideology? A bigot is already a bigot, before he tunes in to “Empire.” It’s not the job of art and entertainment to “fix” that person’s bigotry. And it’s not the job of Black people — in fiction or otherwise — to constantly present only the most noble aspects of Blackness in order to undermine racism.

For anyone who is uncomfortable with “Empire,” literally every Wednesday at 9:30 p.m., they can turn to ABC and watch a photogenic, suburban Black family with photogenic, suburban Black problems on “black-ish.” These are two very different shows, and one is no more representative of the reality of Black life than the other. Because there is no one reality of Black life; and we shouldn’t pine for there to be only one depiction of who we are. Dre and his children’s relationship is supportive and loving; a far cry from the manipulations of the Lyon boys; but these two shows aren’t supposed to give you identical representations of Black fatherhood — no more than “Dallas” and “Family Ties” gave you the exact same representations of White fatherhood.

The time has passed for Black art and entertainment to pander to the White gaze. Black audiences have spoken — and they love “Empire.” And that should be fuel for the creators and purveyors of Black art to continue to fight for more than just adequate representation on television; but to actually gain some ground as producers and writers of Black stories. These current Black shows are all very different stories being told, and the goal should be to fight for more variety — not silencing the voices of those we don’t agree with or relate to.

“Empire’s” social impact isn’t the issue. Society’s reaction to “Empire” is what makes for more interesting dissection. Black people have been conditioned for generations to believe that respectability will save us from the racism that has been a part of our existence for centuries in America; if we just pull our pants up and present ourselves on television as doctors and lawyers, then White supremacy will fade and our people won’t be marginalized and stigmatized. But none of that has ever worked. So maybe it’s time for us to be ourselves — all of ourselves — even when White people are watching. Because our freedom to be ourselves, as brilliant and complex and messy and whatever else we are, is what we’re supposed to be fighting for.

Story by Stereo Williams

Illustration by Lena J