1925.

This was the year that Malcolm X was born. And to quickly provide an overview, things were pretty damn bad for Black people in America.

1965.

Forty years had passed, and Malcolm’s body lay lifeless on the stage of Manhattan’s Audubon Ballroom, riddled with the bullets of an assassin’s sawed-off shotgun. The prevailing wisdom both then and in 1925 was that Black people were dealt a really unfair hand as it related to their place in American society.

2015.

Present day. It’s been 90 years since the birth of Malcolm X, and 50 since his untimely death. And while there have been tremendous strides in recent times, which may suggest to some that being Black is now in vogue; there have been just as many gruesome reminders that there is still so much promise that has yet to be fulfilled.

From Trayvon Martin, to “hands up, don’t shoot,” to the plight of Baltimore, and beyond, there is a growing level of self-awareness currently creeping into the psyche of Black people.

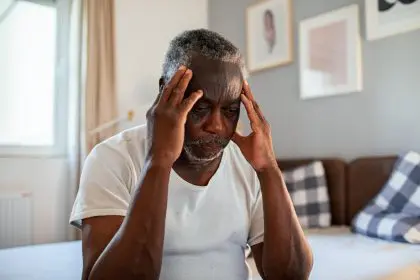

It’s as if we’ve become the prey, and America’s justice system is currently hunting us for sport. It’s a cold-blooded game too, where the lynchings of the ’20s and the water hoses of the ’60s have officially been replaced by the police chokeholds of the new millennium.

It’s not cool.

And more than anything, it’s upsetting. I mean, could Malcolm — while standing on that stage in the final moments of his life — have predicted that 50 years after his death that being a Black man in America would still be so hazardous to one’s health?

I have a growing suspicion that his answer would be an emphatic yes.

What was most haunting was how relevant his words still are in addressing the issues of today. So we reimagined a conversation with Malcolm X, in a world where he was still alive. And by using his own words from past speeches, we were able to gain insight into how he might have handled the current plight of the Black man.

Here’s what we found.

There have been marches from Ferguson to New York to Baltimore, and they all have a common refrain — community leaders have called for more prayer to help combat the political forces at hand. Do you believe that more religion — whether it’s Christianity or Islam — is what is needed to make a significant change as it relates to the treatment of Black men in America?

Islam is my religion, but I believe my religion is my personal business. It governs my personal life, my personal morals. And my religious philosophy is personal between me and the God in whom I believe; just as the religious philosophy of these others is between them and the God in whom they believe. And this is best this way. Were we to come out here discussing religion, we’d have too many differences from the outstart and we could never get together. You and I — as I say, if we bring up religion we’ll have differences; we’ll have arguments; and we’ll never be able to get together. But if we keep our religion at home, keep our religion in the closet, keep our religion between ourselves and our God, but when we come out here, we have a fight that’s common to all of us against an enemy who is common to all of us.(1)

So this common struggle with the Black man has nothing to do with religion and everything to do with race?

America has a very serious problem. Not only does America have a very serious problem, but our people have a very serious problem. America’s problem is us. We’re her problem. The only reason she has a problem is she doesn’t want us here. And every time you look at yourself, be you black, brown, red or yellow, a so-called Negro, you represent a person who poses such a serious problem for America because you’re not wanted. Once you face this as a fact, then you can start plotting a course that will make you appear intelligent, instead of unintelligent.(2)

But it can’t be that simple, can it? As Black people, we are a proud, diverse people who come from so many various backgrounds. How could a people so diverse suffer from blanket oppression?

What you and I need to do is learn to forget our differences. When we come together, we don’t come together as Baptists or Methodists. You don’t catch hell because you’re a Baptist, and you don’t catch hell because you’re a Methodist. You don’t catch hell because you’re a Methodist or Baptist, you don’t catch hell because you’re a Democrat or a Republican, you don’t catch hell because you’re a Mason or an Elk, and you sure don’t catch hell because you’re an American; because if you were an American, you wouldn’t catch hell. You catch hell because you’re a Black man. You catch hell; all of us catch hell, for the same reason.(2)

I understand your perspective. And I also understand that there has recently been a stream of cases where Black men have lost their lives due to excessive force at the hands of the police. Is it fair then for us to judge all police by this standard? Should we as Black people just not trust White police officers?

We’re not against people because they’re White. But we’re against those who practice racism.(1)

But there seems to be so many instances of people being judged solely by the color of their skin — and that’s for better or for worse. What are your thoughts on this?

We don’t judge a man because of the color of his skin. We don’t judge you because you’re White; we don’t judge you because you’re Black; we don’t judge you because you’re Brown. We judge you because of what you do and what you practice. And as long as you practice evil, we’re against you. And for us, the most — the worst form of evil is the evil that’s based upon judging a man because of the color of his skin.

And I don’t think anybody here can deny that we’re living in a society that just doesn’t judge a man according to his talents, according to his know-how, according to his possibility — background, or lack of academic background. This society judges a man solely upon the color of his skin. If you’re White, you can go forward, and if you’re Black, you have to fight your way every step of the way, and you still don’t get forward.(1)

For us to move forward as a people, something needs to be done on the community level. The anger in Baltimore wasn’t just about Freddie Gray. It was about their frustration at the lack of opportunities and resources that their community has been suffering from for years. So with that said, should we then blame the politicians for not instituting laws that would level the playing field for Blacks?

The Black man should control the politics and the politicians in his own community. The time when White people can come in our community and get us to vote for them so that they can be our political leaders and tell us what to do and what not to do is long gone. By the same token, the time when that same White man, knowing that your eyes are too far open, can send another Negro into the community and get you and me to support him so he can use him to lead us astray — those days are long gone too. We must understand the politics of our community and we must know what politics is supposed to produce. We must know what part politics play in our lives. And until we become politically mature we will always be mislead, led astray, or deceived or maneuvered into supporting someone politically who doesn’t have the good of our community at heart.(1)

Baltimore is within earshot of Washington, but outside of a few statements, the federal government has been largely quiet on our issues.

This government has failed us; the government itself has failed us, and the White liberals who have been posing as our friends have failed us. And once we see that all these other sources to which we’ve turned have failed, we stop turning to them and turn to ourselves. We need a self-help program, a do-it-yourself philosophy, a do-it-right-now philosophy, a it’s-already-too-late philosophy. This is what you and I need to get with, and the only way we are going to solve our problem is with a self-help program. Before we can get a self-help program started, we have to have a self-help philosophy.(1)

(1) ”The Ballot or the Bullet” Malcolm X delivered April 12, 1964, in Detroit.

(2) ”Message to the Grass Roots” by Malcolm X delivered Nov. 10, 1963, in Detroit.

Story by DeWayne Rogers

Artwork by Adrian Franks