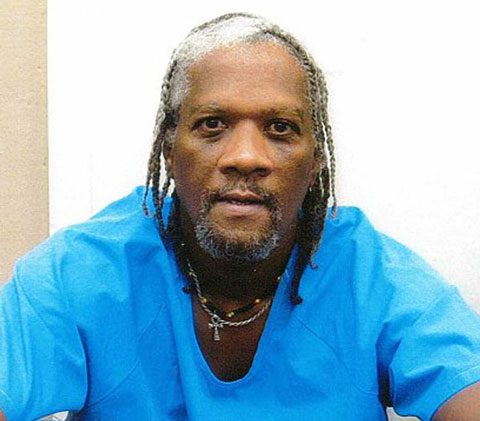

On Sept. 7, 2016, the Louisiana Supreme Court will hear the capital appeal of 25-year-old Rodricus Crawford. I spent three months investigating his case, interviewing 10 people, including the district attorney and Crawford’s appellate attorney, as well as reading all of the appellate briefs and expert affidavits. I concluded Crawford was railroaded. At every turn he was presumed guilty and ultimately convicted of the death of his 1-year-old son who medical experts say died of pneumonia. This is one in a series of articles examining how easy it is for a Black man to end up on death row.

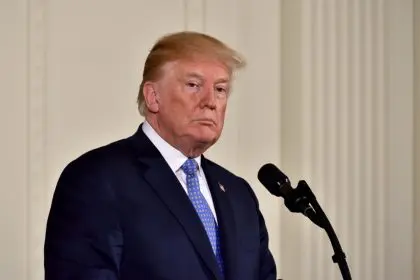

Below is the case of the prosecution in State of Louisiana v. Rodricus Crawford. The case was originally tried by Caddo Parish, Louisiana’s interim district attorney, Dale Cox, who came under fire for making statements like these he gave to The New Yorker:

“Over time, I have come to the position that revenge is important for society as a whole. We have certain rules that you are expected to abide by, and when you don’t abide by them you have forfeited your right to live among us.

“The “epidemic of child-killings” is the result of the “destruction of the nuclear family and a tremendously high illegitimate birth rate.”

After Caddo Parish elected James Stewart, its first ever Black district attorney, Cox resigned and some hoped that Stewart would reconsider the state’s position on Crawford’s case. Instead, Stewart’s office is fighting to keep in place the guilty verdict and death penalty sentence reached under Cox. Below is a summary of the brief signed and filed by Stewart and an assistant district attorney, Tommy Johnson, in opposition to Crawford’s appeal. (Read the brief here.) This piece will be followed by one that focuses on Crawford’s brief.

The prosecution’s case:

One-year-old Roderius Lott (R.L.) was pronounced dead on Feb. 16, 2016. Prior to his death, R.L. had been in his father’s custody since February 12, 2016, his first time in his father’s home. R.L. had a runny nose, but he was not sick. He was playing and eating a lot. No one thought he needed medical attention.

As he had since he was 15, Crawford smoked marijuana daily during R.L.’s stay, including two blunts the last day of the baby’s life.

Sometime after 11 p.m. on the night in question, Rodricus Crawford inflicted head and buttock injuries to his 1-year-old son Roderius Lott’s (R.L.) then smothered the baby between 4 a.m. and 6 a.m. Around 6 a.m., Crawford’s mother, uncle and two siblings were awakened by the sound of Crawford screaming that something was wrong with the baby. Crawford’s mother and sister tried pumping the baby’s chest, but the baby appeared to be dead. Crawford’s uncle called 911. Crawford’s mother fainted. Crawford ran out to meet the ambulance with the baby in his arms.

Both paramedics testified Crawford told them the baby had fallen off the bed. This didn’t sound right to them and after noticing bruises, they alerted the police. Around this time, R.L.’s mother, LaKendra Lott, who lives near Crawford, came down the street to see what was going on. She and Crawford were immediately taken to the police station for questioning.

At the hospital, the coroner pronounced the baby dead. Following a 1-hour autopsy, the state’s brief says the coroner “issued a provisional anatomical diagnosis [that classified the death as a homicide by manual smothering]. He went on to say it could be changed, and in fact, was changed with the addition of bronchopneumonia.”

The prosecution noted in the brief, “motive is not an essential element of murder.” In rebuttal to the characterization of Crawford as a “loving and caring father,” the prosecutor, Cox, commented at trial that Crawford “was living with his mother since majority, he seldom worked, lived off his mother and girlfriend, and sat home doing nothing.”

Furthermore, the brief stated, “The suggestion that no one saw him abuse R.L. is of no merit as abusers often commit these atrocities outside the presence of witnesses.” (Witnesses at trial included R.L.’s mother, his maternal grandfather, both his grandmothers, the mother of Crawford’s daughter, and Crawford’s four relatives who were also in the home the night R.L. died.)

R.L.’s mother, Lott, had a history of mental illness that included bizarre behavior and fighting. Also introduced was Crawford’s criminal record. His offenses follow: unadjudicated possession and use of marijuana as an adult and juvenile; unadjudicated failure to provide child support in violation of a court order; and unadjudicated neglect of his child. (Up next is the case for the defendant.)

More in this series:

Why does this town keep putting innocent black men on death row? (video)

Rodricus Crawford’s timeline to die

Black D.A. James Stewart opposes White defender

White defender mounts appeal, opposes black D.A.